During oral arguments in Fisher v. University of Texas–a case before the U.S. Supreme Court on affirmative action in college admissions–Justice Antonin Scalia suggested that Black students belong in “slower track” schools.

“There are those who contend that it does not benefit African-Americans to get them into the University of Texas, where they do not do well, as opposed to having them go to a less-advanced school … a slower-track school where they do well,” Scalia said. “One of the [legal] briefs pointed out that most of the black scientists in this country don’t come from schools like the University of Texas. They come from lesser schools where they do not feel that they’re being pushed ahead in classes that are too fast for them.”

Then, Scalia cut to the chase.

“I’m just not impressed by the fact that the University of Texas may have fewer [black students if the admissions policy changes],” he said. “Maybe it ought to have fewer. And maybe, when you take more, the number of blacks, really competent blacks, admitted to lesser schools, turns out to be less. I don’t think it stands to reason that it’s a good thing for the University of Texas to admit as many blacks as possible.”

Upon hearing Scalia’s comments, one may conclude that the justice should trade in his black robes for a white sheet. For most of its history, the high court has been held as a bastion of white privilege, in which the disenfranchised, the dispossessed, the disadvantaged—especially Black folks-need not seek justice. Such a declaration from a justice on the highest court in the land is troubling though not surprising. Chief Justice Taney told Black people where to go when he endorsed and solidified their status in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), declaring that Blacks “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

The history of Black people in the U.S. has been one in which our intelligence, qualifications and suitability always were placed in question.

The Fisher case involves Abigail Fisher, who sued after her application to the University of Texas was rejected. She would have us, and the high court, believe that she was denied admission based on her race, while less qualified Black applicants were admitted to the university. However, as Elise C. Boddie, a law professor at Rutgers noted in the New York Times, Fisher was not denied entry based on her race, but rather on “her weak academic profile relative to the rest of the pool,” as the University of Texas made clear.

Boddie mentions that while one Black and four Latino applicants with lower scores than Fisher were admitted, so, too were 42 white students whose profiles were identical or lower than hers. Further, 168 Black and Latino students who were as good or better than Fisher were denied as well. Other cases, Boddie argues, have shown that considerations of race in college admissions do not lead to the denial of qualified whites. The larger issue, however, is the nation’s “impatience with racial inclusion and the journey to overcome our past,” the reluctance of institutions to consider race, even as factors such as geography, or preferences based on legacy, or whether a student’s parents gave a hefty contribution to the school receive significantly less attention.

We can take this a step further, as did Amanda Marcotte in Salon and June Jennings in The Nation, and have a discussion about white skin privilege. Marcotte dismisses Abigail Fisher as a race baiter, and her case as one which aims to boost mediocre white students at the expense of more talented students of color. Marcotte calls the lawsuit a “nuisance suit” that is disingenuous and poorly argued, and with a claim that has been proven untrue.

“Fisher’s case only makes sense if you assume that people of color are inherently less worthy than white people,” she adds, offering Scalia’s comment as proof of the assumption of the inherent superiority of white folks to everyone, even to applicants of color with superior applications. White privilege and superiority, the notion that whites are better and should come first, is the only way one can make this fly.

Meanwhile, Jennings examines the psychology of the backlash against affirmative action, and the myth of the unworthy applicant. Studies have shown that whites, particularly white men, use their negative thoughts about affirmative action to justify their preexisting attitudes about Blacks and other presumed beneficiaries of affirmative action. In addition, the anti-affirmative action self-talk of white people in one study “was used to denigrate the accomplishments of supposed beneficiaries and elevate the status of people (themselves) who usually do not benefit from the policy.”

Marcotte notes that while arguments that affirmative action creates self-doubt among students of color have been debunked, not enough attention is paid to the self-doubt that racism creates among Black and Brown people, and the attendant mental health issues created by racism and racial bias, such as depression, anxiety and psychosis.

And there are many elements missing from Scalia’s line of questioning, which suggest that he is concerned exclusively with Black people knowing their place and staying in their lane. For example, if some students are not prepared to excel and thrive in top-tier schools, then we need to discuss educational segregation, in which poor students are forced to attend inferior and underfunded schools. Their parents are unable to afford tutoring or private school for their children, as working parents they cannot stay home to help them with homework, and cannot afford to live in affluent, predominantly white communities where the public schools are superior.

The notion of a level playing field is fiction. And far too often, for Black children, the challenges are great. There are no mentors to help them realize their potential greatness, no institutions that are willing to take a chance and give them a leg up. Moreover, public schools, the cops, the D.A. and the prisons are working together to keep Black children on the bottom rung of society, creating opportunities for advancement in nothing more than the state penitentiary system.

It should be acknowledged that every college is not the best fit for every student. In a 2012 piece in The Atlantic, Richard Sander and Stuart Taylor Jr. claim there is a “mismatch” in which students are placed in a college in which they are not as academically prepared compared to most other classmates. The authors say the student could have been admitted due to athletic ability or legacy ties to a school, but usually because of race. They also claim that Blacks “will usually get much lower grades, rank toward the bottom of the class, and far more often drop out” than whites.

“Because of mismatch, racial preference policies often stigmatize minorities, reinforce pernicious stereotypes, and undermine the self-confidence of beneficiaries, rather than creating the diverse racial utopias so often advertised in college campus brochures,” the authors argue.

However, Sander and Taylor provide no evidence supporting their thesis that mismatch is primarily a race-based phenomenon, but for an unsubstantiated claim that affirmative action gives preference to upper-class minorities and fails to serve poor and working-class. Moreover, they do not engage the reader with a discussion on merit and what it means, offering instead studies that suggest Black students are disproportionately in the bottom of their class–or more likely to abandon careers in science or academia or a doctorate degree–as proof that they should stay in their lane and attend a lesser school as a key to success. The authors provide no explanation or context regarding institutional racism or the socio-economic challenges facing Black and Latino students, nor do they discuss white mediocrity and the national program of white privilege which always allowed white mediocrity to soar to new heights, as it continues to allow today. Rather, they assume that whites are more qualified and more prepared than Blacks, and all would be better if the latter simply knew their place and did not aim so high.

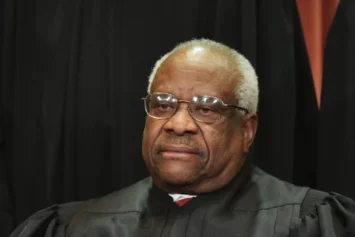

Surely, Justice Scalia’s “slower track” comment reflects a mindset that can result when Clarence Thomas is the only Black person you know.