Black activists are fighting police misconduct and abuse with a new tactic that may surprise many—union contracts. To put it even more bluntly, the #BlackLivesMatter movement is taking the war to the police officers’ home turf, which is the Fraternal Order of Police.

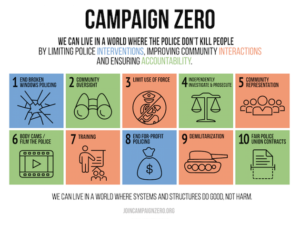

As Krithika Varagur reported for the Huffington Post, four activists of Campaign Zero—DeRay McKesson, Brittany Packnett, Johnette Elzie and Sam Sinyangwe—have created the Police Union Contract Project (PUCP). Campaign Zero was formed to limit police interventions, improve community interactions, and ensure accountability, according to their website. And they gave birth to PUCP because police union contracts stand in the way, making it far more difficult for the public to seek accountability for officer misconduct.

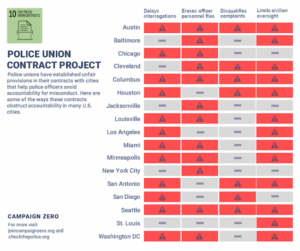

Perhaps this concept has existed under the radar for many people, but it appears that will change. The Fraternal Order of Police, as Huffington Post notes, has 325,000 members, accounting for a third of the law enforcement officers in the U.S. Most large cities’ police officers fall under the purview of this large police union. Campaign Zero created a diagram which unpacks the problem of the lack of police accountability by showing the roadblocks to justice that are built into the union contracts.

In addition, police contracts prevent information on past misconduct from being retained or recorded in a police officer’s personnel file. Cleveland, for example, wiped their police personnel file every two years, before the oversight agreement the city reached with the U.S. Department of Justice. Further, these contracts disqualify complaints of misconduct that are submitted 180 days or more after an incident or that take over a year to investigate. Finally, the union agreements limit civilian review boards from meting out discipline for misconduct.

High profile cases such as the execution of Laquan McDonald, 17, in Chicago–and the killing of other Black children, women and men across the nation–have provided ample evidence of the scope of the crisis in police accountability, and the ways in which cops themselves stand in the way of justice.

Further, the larger issue is that police unions are an outlier in the labor movement. For example, Ed Resnikoff noted in Al Jazeera that the Fraternal Order of Police, which was formed in 1915, chose not to identify as a union, and is not affiliated with the AFL-CIO or the Change to Win Federation. Further, the International Union of Police Associations did not join the AFL-CIO until 1979.

According to Shawn Gude in Jacobin magazine, the behavior of police in light of Black activism has been deplorable of late.

“The proper constituency of a union isn’t simply its membership, but the entire working class,” Gude argues, and yet, “police unions aren’t institutionally equipped to be anything other than anathema to this cause.”

As Michelle Chen wrote in The Nation, it is hard, at least on the surface, to argue against police unionization, assuming everyone has the right to organize.

“But what to make of a union of workers who have historically been charged with breaking strikes and protecting the property of corporations?” she asks. “As pivotal cogs in the machine, cops may suffer from poor working conditions or job insecurity. But when they’re arbitrarily arresting kids or tear-gassing protesters, they are complicit, and instrumental, in a system that’s in many ways inherently corrupt and anti-democratic.”

A police union at odds or even worse, at war with the community, was in full view following the execution-style of killing of two NYPD officers in 2014. Patrick Lynch, head of the New York Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, the NYPD police union, declared that “we have become a wartime police department.” Presumably they are at war with the Black community and #BlackLivesMatter protesters. He also accused of Mayor Bill de Blasio and others of having blood on their hands.

Further, if police unions act against the interests of working people in the communities they “serve,” and certainly are justly accused of being racially insensitive to Black communities, consider that police unions may not even serve the interests of Black police officers.

How can we explain the existence of Black police organizations, and the shooting, even killing of Black officers by their white colleagues in so-called cases of friendly fire? Just ponder that for a minute.