An American commentator once said that Canada is like the United States, except without the bullsh*t. However, “Ninth Floor,” a documentary from independent Canadian filmmaker Mina Shum reminds viewers that Canada has its problems with racism as well, and it is incumbent upon all of us to remember the lessons of history, lest we repeat past mistakes.

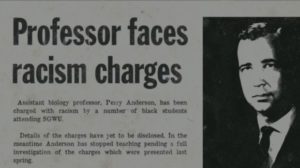

The National Film Board documentary, which just premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival, recalls the infamous “Computer Riot,” the February 1969 protest and sit-in at Sir George Williams University in Montreal, now Concordia University. Hundreds of students barricaded a ninth floor computer room at the campus in order to bring attention to the lack of responsiveness of the administration to charges of racism. Nearly a year earlier, six Caribbean students had complained about the conduct of biology professor Perry Anderson, a white man the students accused of racism against them. What these Black students experienced was not unlike what Black people and immigrant groups experienced throughout Canada, just as African Americans and other groups of color were coming of age and political consciousness, and railing against racial discrimination and injustice in Canada’s neighbor to the south.

After two weeks, what was a peaceful protest was met with the force of riot police. Students were beaten, nearly one hundred were arrested, as Think Progress reported, and one student never recovered. Others were deported. A suspicious fire had been set in the building, allegedly by police–for which the students were blamed, however implausible it would seem–as people below shouted “Let the niggers Burn!”

Among the protesters were Roosevelt Douglas, the future Prime Minister of Dominica, and Anne Cools, would later serve as a Canadian senator.

In 1969, violent protests and a 14-day sit-in over racism at Sir George Williams University exploded. Police and riot squad officers stormed the computer room, arresting 97 people. (Ninth Floor/NFB)

“Canadians are racist, but they like to apologize for being racist,” one of the protesters proclaimed in the film.

Through documented footage and interviews, the film tells a story that should resonate with audiences in a twenty-first reality of #BlackLivesMatter, in which law enforcement responds to peaceful protesters with state violence. Further, the actions of government, police and university officials harken back to the COINTELPRO program in the U.S., in which the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover monitored activists, disrupted social movements and incited acts of violence. Lives were destroyed, as activists and leaders were imprisoned and murdered.

A Canadian of Chinese descent, Shum said she had been unaware of the 1969 protest growing up in Canada. “I didn’t know about it, and I grew up in Canada. In what was post-multiculturalism, in the 1970s, our official policy was this mosaic,” she told Think Progress. “Even though there’s racism in the playground, in my father’s workplace, racism will never go away, that’s fine. We can meet it as it comes. But the fact that it had not been told in history, in our journey towards a multiculturalism state, was shocking.”

Biology teacher, Perry Anderson, was accused of unfairly grading black students at Sir George Williams University. (Ninth Floor/NFB)

“Canada prides itself on being better at most things!,” Shum argued. “We do strive towards humanitarianism. The film is to say: Look, we still have more work to do. We can get lazy. That’s where my heart is coming from.”

“And my personal belief is, if you’re going to evolve as a human and a society, we must admit our faults. When I talk about this case, I talk about ‘we.’ We did this. We as humans. This is part of who we are, and we have to accept and allow that and then move forward from that. Until we all put this story on the table, we’re spending a lot of energy trying to look perfect,” she added.

“It was quite moving, very, very moving. There were so many elements that I had forgotten and to see them all packaged in the film was quite profound for me,” Rodney John–one of the original six biology students who complained of racism, and a narrator in the film–told CBC about “Ninth Floor”. “What the film did was bring to consciousness to awareness, that the fire was the culmination, the expression of all of the frustration, the anguish, the agony,” he added.

John, now 73, recalled the racism he and other students had experienced:

During that academic year, every single West Indian student, and there were about 14 of us in the class, had issues with Anderson. He called us by our honorifics — Mr. This and Ms. That — whereas he called the white students by their first names. And his response to that was, well, he was simply being polite to the black students, and as for the white students, well he knew them….

[Biology student] Terence had a white lab partner. Terence wrote his lab, handed it in, it was returned marked, and he got 7/10 for it. His white partner borrowed his lab after it was marked, copied it word for word, including grammatical errors, and got 9/10 for the same particular lab. Each of us had an experience with Anderson, at least one.

John learned that Professor Anderson is going to have a Black great-grandchild, which he said placed things in a different perspective.

“Ninth Floor” reminds us that it is important for society as a whole to reckon with its past, as victims pay the ultimate price when that past is hidden from plain view.