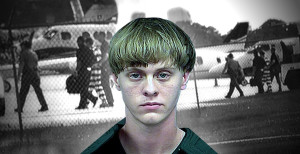

After meeting with families of the victims in the Charleston massacre, state prosecutors in South Carolina announced the decision to pursue the death penalty against Dylann Roof. The families of those slain remain divided on the death penalty for the mass murderer.

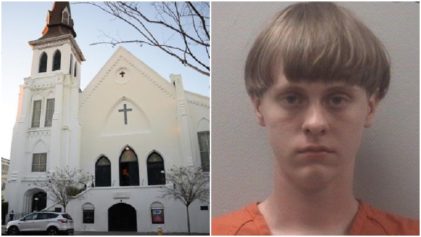

On June 17, the lone gunman walked into Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, the historically Black church involved in the Denmark Vesey slave rebellion of 1822. After sitting in a bible study for nearly an hour, the gunman hurled racial insults as he shot nine people to death with his .45-caliber semiautomatic handgun. The nine victims ranged in age from 26 to 87, and included Rev. Clementa Pinckney, the church pastor and a state senator.

Roof, who was indicted for the murders, is an avowed white supremacist and neo-Confederate sympathizer, a factor which led to public debate on the flying of the Confederate flag, and the eventual removal of the flag at the state capitol in Columbia.

Roof has been indicted twice in the killings—in state court, and federal courts. However, the decision by South Carolina state solicitor Scarlett A. Wilson marks the first prosecutor to publicly seek execution for the gunman. Gov. Nikki Haley had called for the death penalty in the case. Federal authorities have not yet indicated whether they will seek death for Roof regarding his hate crime indictment.

According to documents from the prosecution, Roof “knowingly created great risk of death to more than one person in a public place, by means of a weapon” and killed more than two people, which are sufficient criteria to seek the death penalty.

Wilson noted that some of the victims’ family members oppose the death penalty altogether due to their faith, while others thought life imprisonment was a more practical and preferred option. Some of the families, however, believed death was appropriate, as the New York Times reported.

“This was the ultimate crime, and justice from our state calls for the ultimate punishment,” Wilson said in a statement.

She said while she understands that some family members want to forgive Roof, there are still consequences for his actions.

“Making such a weighty decision is an awesome responsibility,” Wilson said. “People who have already been victimized should not bear the burden of making the decisions on behalf of an entire community. They shouldn’t have to weigh the concerns of other people. They shouldn’t have to consider the facts of the case.”

Andy Savage, a Charleston attorney who represents some of the survivors and victims’ families, commended Wilson for considering his clients’ thoughts on whether Roof should face death. Some of his clients may oppose the death penalty for religious reasons but also understood the decision was up to the state, Savage said.

“In the big picture, if you see why these people are involved, it’s because they were in a church on a Wednesday evening at Bible study,” Savage said. “They’re not Sunday Christians. They’re 24-7 Christians. They believe in the sanctity of life. They believe in forgiveness. So for them, to not be proponent of the death penalty is no surprise.”

The decision to the pursue death penalty against Roof reflects public pressure and media attention brought to this high-profile case. Moreover, that many of these Black family members oppose the death penalty–despite this horrific mass murder– reflects a sense of forgiveness among African-Americans that may not be as prevalent among white victims. The concept of forgiveness in Black culture is one that stems from their religious convictions, deeply rooted in the Black church and a legacy of slavery. For Black people subjected to the violence of slavery and Jim Crow, forgiveness was not to please white folks, but rather was a matter of survival, even as we have sought justice for the wrongs committed against us.

That legacy of forgiveness is reflected in divergent racial attitudes on capital punishment. A 2013 Pew Research Center poll found that support for the death penalty was significantly lower among Blacks and Latinos than whites, with 36 percent of Blacks favoring death and 55 opposing it. Half of Latinos oppose capital punishment and 40 percent support it. Meanwhile, 63 percent of whites favor the death penalty, as large majorities of white evangelical Protestants (67 percent), white mainline Protestants (64 percent) and white Catholics (59 percent) are apparently not willing to forgive. Lower approval for the death penalty among Blacks helps to explain why white prosecutors attempt to exclude Blacks from juries in murder cases, in violation of the law.