By Shelby Jefferson

In early 1980s Detroit, between the climate of a post disco era and the economic collapse of a city once at the center of the U.S. automobile industry; amid a budding hip hop invasion in the boroughs of New York and the rising allure of Chicago’s house movement, a musical revolution was emerging from the depths of the Motor City. The revolution was driven by growing technological possibilities, machine aesthetics and funky electronic rhythms.

The hub of this subcultural surge was the western suburb of Belleville, Mich., where high school friends Derrick May, Juan Atkins and Kevin Saunderson began DJing at local parties and experimenting with synthesizers. The three DJs were transfixed by the funky grooves of Parliament Funkadelic and Kraftwerk’s German “robot pop” and inspired by a radio DJ named the Electrifying Mojo who spun everything from Prince and Jimi Hendrix to Peter Frampton and the B52’s.

These young originators would eventually meld electro-funk, synth-pop and Italo-disco influences with futuristic synths and captivating dance beats to yield a harmonic, mechanistic and youthfully stimulating sound that sparked an electronic craze all over the world. From rave parties in New York City, to the pop scene in the United Kingdom, this music—inherently Black and uniquely Detroit—was called techno.

Around the same time, a young sculptor was coming of age in

the neighboring community of Inkster. Inspired by this developing genre nurtured by fellow middle-class Black intelligentsia, M. Scott Johnson befriended local DJs who rocked turntables at neighborhood parties, and frequented a club called The Music Institute, the utmost hangout spot for Detroit’s techno and house aficionados. Venturing to Africa to study stone carving during the mid-1990s, Johnson eventually combined his passion for techno with a burning love for the visual arts, ultimately creating unique narratives surrounding rhythm, structure, the African diaspora and Black musical influences to generate some of the most intriguing sculptures ever produced.

Many of these works are now on display in an exhibition called “Shadow Matter: The Rhythm of Structure—Afro Futurism to Afro Surrealism” at Detroit’s Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History. Marking Johnson’s first showcase to ever open in the state of Michigan, the exhibit presents 34 captivating pieces saturated with aesthetics of traditional and modern African carving, Zimbabwean Shona ideologies, concepts of Afrocentric/non-Western cosmologies and one less obvious point of inspiration, an intrinsic connection to the art of techno.

“Techno taught me how to organize abstraction in my mind; the repetition opens up corridors of your conscious thought,” Johnson explains. “Working with stone in Africa, you see how rhythm manifests itself physically. If your beat is erratic, the stone responds erratically which makes it harder to carve. If you’re doing it more rhythmically, it opens up and allows you to work in harmony with whatever your medium is.

“As a sculptor, I’m constantly carving to my own private orchestra. I’m wrapping myself up in the drama of the music; remixing and reediting rhythms in my head, adding my own sound with a chisel and a hammer. There’s never been a separation for me. 99 percent of the time, you’ll find that techno is playing while I’m working in stone.”

Johnson’s immersion in the nascent world of techno came at a time when a fledgling hip hop community was experiencing a similar evolution. From the realms of the South Bronx, DJ Afrika Bambaataa had created a new sound unseen in the rap world, combining funk and European influences with synthesized beats, digitalized samplers and vocoder technology to generate what became known as electro music. In 1982, upon Bambaataa and the Sonic Force’s release of the electronic rap anthem “Planet Rock,” dancers were left breaking to the beat, as graffiti artists tagged subway trains with their own visual interpretations of an emerging movement developing among the city’s restless youth culture.

Nevertheless, for Johnson in Detroit, it was Cybotron, Model 500, Derrick May and other techno pioneers who nurtured a profound understanding of how electronic music can be translated into a visual medium—one that would allow him to explore endless possibilities throughout his career as a sculptor.

“People often talk about the correlation between graffiti and

hip hop, but I was always wondering: What’s the visual response to techno for African American artists? In techno, the undulation of the line is like a replication of the beat, so there’s an over exaggeration that allows you to interpret the music in a very abstract way – similar to how artists translate hip hop into graffiti writing.

“I learned the relationship between visual art and music by listening to techno, so one of my objectives in bringing this exhibit to the Detroit area was to allow for Black people from similar backgrounds to identify with these connections in my work.”

These connections are ever-present throughout “Shadow Matter,” where the genre’s abstract movement, sonic harmony and rhythmic energy spring to life, ultimately unveiling Johnson’s radical brilliance as an artist. In an exhibit divided into subsections that include “Family,” “Mythology” and “African American Folklore,” Johnson’s “Music” portion stands out as the most intriguing of all—housing a marble tribute to groundbreaking producer Anthony Shakir and a Springstone carving that pays homage to Derrick May and his definitive techno tune “Strings of Life.”

“Anyone who knows techno will identify “Strings of Life” as the anthem that really cemented the movement, so it definitely stands as a cornerstone of what I’m talking about as an artist and how I relate to music,” Johnson says. “Going back to when I was studying in Africa, I quickly had to overcome my fear of snakes. To free myself from this anxiety, I would put on headphones at night, listen to this song and walk silently through the forest. This music completely formatted my hard drive. As a result, I created a bust of [Mays’] head to honor his spirit, in addition to the movement from which all of this was created.”

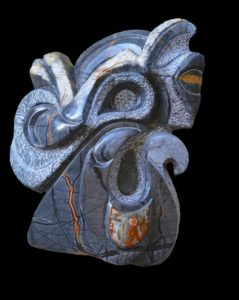

While pieces like “The Bust of Derrick May” explore explicit techno ties, other pieces are more intangibly connected to the genre. According to Johnson, certain sculptures present very literal features such as an eye or a hand, while less perceptible lines or patterns explore the dynamics of movement and rhythm that correlate with the erratic compositional structure of the music. This may be most evident with abstract figures like “Africoid Cranium” and the “The Target – Elizabeth Catlett Remix,” two figures that perhaps, more than an others in the exhibit, effectively demonstrate how Johnson has successfully interlinked two entities rarely associated with one another in the artistic world.

“In a piece called ‘Africoid Cranium,’ I look at the development of physical characteristics among the races over time, while also playing off of scientific racism that once designated African skulls as animalistic in comparison to Europeans. I created a positive, futuristic piece depicting a cranium, and additionally chose a title that could definitely be used in the branding of an actual techno track.

“We also hear a lot about DJs and musicians who utilize the concept of remixing, but you never see that among visual artists, so I created a remix of Elizabeth Catlett’s famous sculpture ‘Target’. With me bouncing off of the original aesthetic, the movement of the music is reinterpreted into a visual experience from an abstract expressionist standpoint. Very much like techno, my sculpting and photography is all about working multiple layers around the melody to see what I can create.”

Overall, as a renowned sculptor with featured collections in venues around the world, Johnson’s reverential interpretation of techno music as a visual medium grants access into the origins of yet another appropriated genre much removed from its ties to the African American experience, and in this case, Detroit’s Black community. Sadly, as techno ultimately gained international footing in the late 80s and early 90s (particularly among European audiences), many of the genre’s pioneers who dared to change the world by exploring the endless possibilities of technological innovation and electronic sound, stood largely overshadowed by white-Euro acts. Thankfully these originators, the godfathers who sparked a global musical revolution, planted a creative seed in one exceptional sculptor intent on preserving their legacy for many years to come.

“When you look at commercialized genres of today like Electronic Dance Music (EDM), they’re a sort of bastardization of what techno music is really about,” Johnson explains. “Looking at the effects of that, there are always issues involving appropriation and who’s stealing whose ideas creatively. Even at the annual Movement Festival in Detroit, a lot of the Black DJs are somewhat separated off the beaten trail, while whites and Europeans dominate the major stages. So the people actively creating this music are kind of ostracized. That’s definitely a continuing problem.

“I came up at a time when this movement was born; when techno was music that actually affected us. I greatly admire extraordinary artists like Derrick May, Anthony Shakir, Larry Heard and Alton Miller, all of whom became a source of inspiration for me when I began carving stone. I want to be able to honor those who haven’t received their due credit, and have contributed so much to this genre, and furthermore to the entire world. This will definitely stand as an ongoing root concept in my work as a visual artist.”

Johnson’s work will be featured at the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History through August 30. For more information, please visit TheWright.org.