By Gus T. Renegade

The foundation of United States cinema and entertainment is Black death. D.W. Griffith’s Birth of Nation marked its 100th anniversary in February of this year. The film broadcasts the Klu Klux Klan as benevolent defenders of “the Aryan birthright,” endangered by post-Civil War “negro” aggression. Griffith left no ambiguity about his motivation, which was, “[to] demonstrate to the world that the white man must and shall be supreme.”

AMC’s nuclear hit The Walking Dead does not deviate from the script. In reviewing the season five finale, Justin Moyer notes, “African American men seem over-represented among those who bit the dust.”

The big top circus is no exception. Emory University’s Benjamin Reiss documents that in the 19th century, P.T. Barnum purchased an enslaved Black female named Joice Heth. He marketed her as a “curiosity,” a Black “freak show.” When Heth died, he made a spectacle of her autopsy, charging 50 cents admission to more than a thousand white spectators. Reiss reports that Heth generated substantially higher profits for Barnum once she died.

Blackface, zombies and clowns are amusing. But lynching is a sacred pastime. Legal scholar Patricia J. Williams reminds us that, “Whole towns routinely turned out for ‘n-gger barbecues.’” Classes halted so that white children could partake in the “communion-like dispersal of Black flesh.”

Contemplate the “haunting symmetry” between 20th century lynching photos and the 21st century video montage of police terrorism against Black citizens. Isabel Wilkerson, a journalist and Pulitzer Prize winner, says the recorded deaths of Eric Garner and Tamir Rice “have reached hundreds of thousands of watchers on YouTube – a form of public witness to brutality beyond anything possible in the age of lynching.”

The communal consumption of Black carcasses is increasingly a

An escalating number of Hollywood scripts are plagiarized from Black obituaries.

It’s likely that Oscar Grant’s white killer spent fewer days in custody (365) than the time to produce Ryan Coogler’s Fruitvale Station. Coogler is an Oakland native and a gifted Black filmmaker. His goal was to introduce Grant as a son, a father, an imperfect human willing to advise a white stranger’s fish fry. However, author and filmmaker Andre Seewood senses a contradiction. “Whites are going to a movie where a white [officer] has no racial empathy and kills a Black [person].” Ostensibly, viewers demonstrate – or cultivate – empathy for Grant, Black people in general, by watching the film. However, the simultaneous debut of Grant’s biopic with the conviction-less conclusion to Trayvon Martin’s murder trial suggests boundless contempt for Black life. Not empathy. Critical race theorist Dr. Tommy Curry submits that these theatrics are a component of a racist system that demands and “accepts the normalcy of Black death.”

Predictable Black death inspired white photographer Gillian Laub to produce the HBO documentary, Southern Rites. Grammy winning pianist John Legend contributed to the soundtrack and executive produced the film. Laub initially investigated a rural Georgia town that continued to hold separate proms for white and Black students; she was sidetracked by the 2011 shooting death of Justin Patterson. He was unarmed, 22 and Black. The film stars Norman Neesmith, the 62-year-old white killer, who was given a plea deal which confined him to a special detention program but required no time behind bars. Laub provides Neesmith a close-up to proclaim that terminating a Black life “was doing the right thing.” This documentary – like most showcases of violence targeting Black people – allegedly subscribes to Patricia Williams’ appeal for “reflection rather than spectacle… vision rather than voyeurism… study rather than exposure.”

Unfortunately, this seamless, morbid projection confines Black existence to death. Dr. Curry writes: “Not being able to think of [Black people] beyond their [corpses] is the real result of racism’s dehumanization. Racism ‘thingifies’ Black life, and the reduction of Black [lives] to the event of their dying leaves the aim of racism, accepting the racially oppressed as not human… unquestioned.”

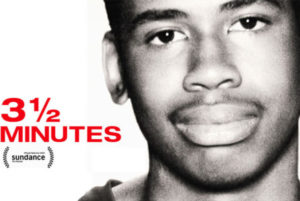

Marc Silver is an English filmmaker who crossed the Atlantic to question the 2012 murder of Jordan Davis. The film, 3 1/2 Minutes, 10 Bullets, riveted audiences at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. It’s slated for a limited theatrical release later this month, and HBO will air the documentary this autumn. Ijeoma Oluo talked with Jordan’s father, Ron Davis, about “the life-saving potential” of the film. Davis said, “When the jury of the Trayvon Martin trial said they ‘couldn’t connect with Trayvon,’ that really hit me.” He hopes 3 1/2 Minutes will “make sure that everybody [can] connect with Jordan.”

Convicted white killer Michael Dunn did not connect with Jordan. Dunn’s conduct during the trials convinced Davis that, “he had a lack of empathy for [his] son. He didn’t care that he killed Jordan.” Oluo emphasizes, “This lack of empathy gets to the heart of why this documentary was so important to Davis [and Jordan’s mother, Lucia McBath.]”

Regrettably, this ceremony of white terrorism and Black trauma is “stunningly routine” because Michael Dunn exemplifies the white collective. Harvard University doctoral candidate Jason Silverstein substantiates that white folks’ inability to empathize with Black people “perpetuates racial disparities” like the killing of Trayvon Martin or Jordan Davis.

Importing British documentarians won’t change this.

Nick Broomfield also hopped the pond in pursuit of Black bodies. Tales Of The Grim Sleeper examines suspected Black serial killer Lonnie Franklin, who allegedly preyed upon destitute Black females of South Central Los Angeles for a quarter century. Its HBO premiere was in April. It’s inconceivable to grasp how a “real-life” depiction of Black people as crack heads, whores and thugs will rehabilitate white appraisal of Black life. Pam Brooks – a retired prostitute, recovering substance abuser, and Black grandmother – stars in the film and shares her gratitude for Broomfield’s interest in “these Black people’s lives.” She delivers a magnificent summation of this essay and clarifies how an undetermined multitude of Black females could be butchered for decades.

“The police don’t care because these are Black women. It’s not like Lonnie killed no highbrow white folks, you know. I mean, we don’t mean nothing to them. We’re Black.”

It’s lucid to suggest these films inform viewers about disregarded Black lives and the lethal, concealed operations of racism. But the commodification and consumption of Black suffering should authorize gargantuan suspicion. African-American Studies scholar Dr. Natasha Barnes warns that showcasing the violation of Black people can easily reinforce “the truth of white power and the domestic terror that undergirds it.”

When Jack Johnson bludgeoned and conquered Tommy Jeffries to become the first Black heavyweight champion in 1908, white supremacists discontinued filming. They wanted to spare white folks the indignity of witnessing melanin dominance, white destruction. Reverse logic is employed for any and all Black agony.

Gil Scott Heron’s revolution won’t be airing, but Black death will be televised.