Today, taking a “selfie,” or a picture of oneself, is a historically insignificant act that happens for many Americans dozens of times throughout one day, but in the 19th century there was so much time and planning poured into self-portraits.

So when a group of students from the University of Michigan were given the task of researching the images, it comes as no surprise that the old photos helped unlock many new details about African-American life during that time.

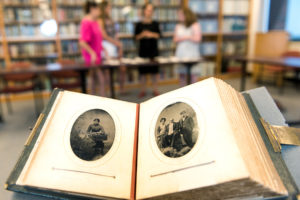

It was a year ago that Clayton Lewis, a curator at the University of Michigan, uncovered the rare set of photo albums and handed them off to U-M professor Martha Jones who then trusted her students to uncover the history behind each photo.

By the time they were done, the history of Arabella Chapman began to come to life.

“She was born in Jersey City, N.J., in 1859, less than two years before the outbreak of the U.S. Civil War and the abolition of slavery,” an article published on the U-M website explained. “The students discovered that her family, including she and her parents, John R. and Harriet Alfarata moved wit her brother William, to Albany, N.Y. in 1864, where her younger brothers John and Charles were later born.”

According to Jones, that move marked a pivotal moment in the family’s history.

“It’s likely that they moved there because, for African-Americans in the mid-19th century, Albany held an important place in political culture,” Jones told the university newspaper. “It had been home to key Black abolitionist activists including Stephen Meyers, whose daughter Liz is picture in the Chapman albums.”

Other people captured in the albums included historical figures like Abraham Lincoln, John Brown and Frederick Douglass.

“From their fashion to their ideologies, the unaltered albums show this family as they hoped to be seen and remembered,” Jones added.

That’s perhaps the greatest difference between the 19th century selfies, laced with hints about culture and lifestyles of the past, when compared to the convenient and often meaningless selfies of today.

Because taking a photo in the 19th century was an occasion that took all day, there was a lot of thought and planning behind what the subjects would wear and what kind of props they would hold.

“Back then, the portraits were very planned out, and it was interesting to consider how a woman from that era would want to represent herself,” said one U-M senior Emily Moore.

But Moore actually believes that the cultural significance behind the self-portraits is what makes the selfies of today more like the selfies of the past.

“I’m actually not that different from Arabella—it may be easier to take a photo now, but I also have control of which ones I decide to share of myself or my life,” she added.

Either way, the truly remarkable part of the project was about more than just the exploration of the early age of self-portraits.

For U-M women’s studies major Katie Diekman, it was about the way Arabella portrayed herself in the images and how she hopes to mirror a strong Black woman from the past.

“Arabella, as a woman and an African-American had to overcome much more than I have had to do,” Diekman said. “I saw a kind of strength in her portraits, and that’s how I’d like people to remember me—as a strong woman.”