Sunday marked the 61st anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education ruling and it should have served as a day for all Americans, especially those in the Black community, to celebrate what years of equality has managed to do for their own lives and the future of their children. It should have been the day that parents and students all across the nation were able to celebrate an academic landscape where students of all color were able to flourish in a learning environment that was healthy, safe and promoted quality learning.

Instead, the 61st anniversary of this decision only served as an unfortunate reminder that this iconic Supreme Court ruling only granted Black students the right to sit under the same roof as their white peers. It did not, by any means, promise them equality in education.

The latest statistics offered by the U.S. Department of Education can easily be described a national embarrassment for a country that has already given itself a “post-racial” title while boasting to be a land full of opportunity for all.

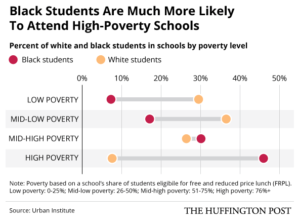

School districts with a predominantly Black student body still tend to get less funding than the schools in districts with a heavier populate of white students, according to the U.S. Department of Education’s data.

In states like Nevada and Nebraska, the percentage gap in the amount of funding per student for “high-minority” and “low-minority” districts comes in at more than 10 percent for the 2011-2012 school year.

Those types of gaps mean that large numbers of Black students are going without essential resources like updated textbooks or education-based technologies, while many of their white counterparts have entire courses planned around such luxuries.

While Americans tend to use technology more than many of their counterparts from overseas, there are still a large number of school districts that don’t have enough computers to accommodate their student body. Others don’t have enough funding for an efficient Internet subscription.

To make matters worse, the disparities for Black students don’t stop there.

Statistics also revealed that students in “high-minority” school districts were more likely to have teachers with a weaker set of qualifications than educators in surrounding districts.

“Students who attend high-minority schools often receive instruction from the least-qualified teachers,” the Huffington Post reported before noting that President Obama has made strides to change such a drastically flawed distribution of educators. “In 2014, the White House announced the Excellent Educators for All initiative, which calls on states to develop plans that would more equitably distribute the best teachers.”

While it’s a promising initiative it also draws more attention to the fact that more than 60 years had to go by since national leaders made a meaningful move to actually ensure that students of all races and socioeconomic backgrounds were still given the same type of opportunities allotted to children from more affluent backgrounds.

For all these years, however, the negative impact of such disparities has only continued to grow.

This means an overwhelming amount of Black students are relying on schools to provide the types of educational resources that they can’t get at home or anywhere else outside the classroom.

But years of inexperienced teachers and insufficient funding have left such students desperately trying to climb out of the unforgiving grasp of poverty—a task that is still extremely challenging with a high school diploma and nearly impossible without one.

“White students and black students graduate high school at different rates,” the Huffington Post reported. “In 2013, 71 percent of African-American students graduated. Eighty-seven percent of white students did.”

Many experts believe such a trend has a lot to do with the lack of Black educators to provide Black students with guidance and the racially biased applications of zero tolerance policies that usually shove students of color into the school-to-prison pipeline.

Even as student bodies start to diversify, it’s far more likely that when all the students file into the classroom they will be looking up at a white teacher. While race is clearly no indication of how qualified an educator might be, a series of studies have proven time and time again that there are unique benefits for Black students being taught by a Black teacher.

“Teachers of color can serve as role models for students of color,” the Center of American Progress noted in a 2014 report. “When students see teachers who share their racial or ethnic backgrounds, they often view schools as more welcoming places.”

That luxury is rarely allotted to Black children since, according to the National Center for Education Information, only about 7 percent of all K-12 teachers were Black in 2011. Meanwhile, nearly 85 percent of that same population was white.

As if these obstacles weren’t enough, zero tolerance policies and implicit racial bias is yet another towering hurdle that Black students are asked to leap over while many of their white counterparts have bolted ahead on their own relatively hurdle-free track.

Teachers have been found to be more harsh in their punishments of Black students because implicit racial biases create different perceptions of a Black child misbehaving versus a white one.

Consider stories like the Black high school student in Louisiana who was actually hit with assault charges for tossing what was believed to be Skittles at a classmate on the bus. The student was suspended, served jail time and his days out of the classroom were marked as unexcused absences.

Their white counterparts are far less likely to be slammed with such a punishment.

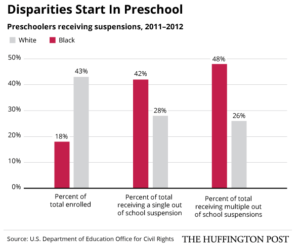

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights found that Black students are expelled or suspended from school at nearly three times the rate of white students and this trend starts well before they reach the halls of middle school.

While Black students only made up roughly 18 percent of all enrolled preschoolers for the 2011-2012 school year, they accounted for more than 40 percent of single school suspensions. That percentage increased by more than 5 percent for students who have received multiple out of school suspensions.

So while the Brown v. Board of Education ruling was truly historic and monumental, it was not the sole Supreme Court ruling that could truly provide equal education for all students regardless of their race or socioeconomic background.

For more than 60 years Black students have been allowed to sit in the same classroom as their white peers while still living a very different reality inside the very same walls. For this reason, the 61st anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education isn’t a milestone that should come with too much celebration.

What it can be, however, is the spark that lights a fire under both state and federal legislators, pushing them to realize that the dream of equal education for all is a dream not yet realized.