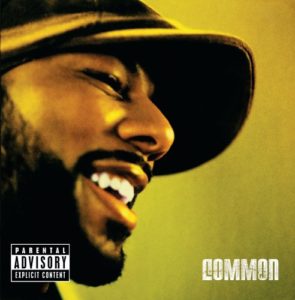

Believe it or not, May 24 will mark the 10 year anniversary of Common’s classic album Be. Viewed as an epic comeback following a lackluster reception to 2001’s Electric Circus, the rapper’s sixth studio release, bathed in a medley of 70s soul, jazz, funk and gospel influences, arguably ranks as one of his most definitive works to date.

Long before Be ever hit the scene, Common had successfully established himself as an influential emcee who, over a 13 year time span, wowed audiences with a lyrical prowess and radical intellectualism that offered a profound alternative to mainstream rap narratives. With poetic odes about hip-hop’s commercial downfall (“I Used to Love H.E.R.”), and revolutionary tales chronicling the perils of the Black liberation struggle (“A Song For Assata”), Common became a rapping griot of sorts who utilized the spoken word tradition to address pertinent social issues affecting the Black community.

Moving past the disappointment of Electric Circus, arguably his most musically experimental work to date, Common’s Be, which was released in a commercialized era of sex, drugs and bling, emerged as a breath of fresh air for hip-hop fans, ultimately marking the return of the socially consciousness mastermind many of us had so deeply grown to love.

Be went on to sell 800,000 copies, eventually earning four Grammy Award nominations. Featuring only 11 tracks and very few guest appearances, numerous factors elevated the acclaimed album, from Common’s authentic portrayal of Black urban life (particularly relating to his hometown of Chicago), to a brilliant soundscape of 70s soul vibes, old school beats and slick vocal sampling compliments of fellow Chi-Town native, rapper/producer Kanye West (who produced nine of the album’s 11 songs). Simply stated, Be spoke directly to the soul. And regardless of who you were and where you came from, there was something about it that deeply moved you to the core.

Perhaps it was the conscious defiance captured in the condemnation of a “lying” George W. Bush on the title track/intro, or the gap bridged between generations on a resounding street symphony featuring the legendary Last Poets called “The Corner”. Maybe it was the raw exposure of weak industry rappers in “Chi City,” or Common’s aptitude for storytelling in “Faithful,” a heart wrenching tale about a woman desperate to save her falsely accused lover from prison who, in the end, had actually forged the crime herself.

Now, 10 years later, Be is still an authentic, organically sound masterpiece from beginning to end, that upon its release in 2005, seemed to demonstrate that Common was definitely back and here to stay. Or was he?

Today, Common has successfully expanded his brand far beyond the realms of the hip-hop world. The rapper (born Lonnie Rashid Lynn) has transitioned into acting, and recently won an Academy Award for “Best Original Song” following the release of “Glory,” a musical collaboration with singer John Legend from the 2014 movie Selma. Needless to say, Common’s growing visibility continues to propel him to unforeseen levels of prominence among popular audiences. But at what cost?

As police violence continues to claim Black lives around the country, Common’s well-established expertise on sociopolitical disparities and the Black struggle may be needed now more than ever. But the South Side Chicago rapper’s radical demeanor seems to have taken a back seat to the introduction of a more meek, accommodating public image well suited for the domains of Hollywood respectability.

Recent interviews reveal a stark ideological contrast from the days of old. The rapper, who once spoke the language of the people, now exemplifies a type of “New Black”—a conceptual term coined by Pharrell Williams during a televised conversation with Oprah. In the interview, the “Happy” hit maker blindly stated, “The “new black” doesn’t blame other races for our issues. The “new black” dreams and realizes that it’s not a pigmentation; it’s a mentality. And it’s either going to work for you, or it’s going to work against you. And you’ve got to pick the side you’re gonna be on.”

However, the “New Black” identity represents a romanticized mentality of progressive Blackness marked by self-accountability and a “we are the world” approach to race relations and social justice issues in the U.S. And to the shock and dismay of many fans, Common expressed very similar philosophies during a recent appearance on Comedy Central’s The Daily Show.

“We all know there’s been some bad history in our country,” he said. “We know that racism exists. I’m extending a hand. And I think a lot of generations and different cultures are saying ‘Hey, we want to get past this’. We’ve been bullied and we’ve been beat down, but we don’t want it anymore. We’re not extending a fist and saying, ‘Hey, you did us wrong.’ It’s more like ‘Hey, I’m extending my hand in love. Let’s forget about the past as much as we can, and let’s move from where we are now. How can we help each other? Can you try to help us because we’re going to help ourselves, too’ That’s really where we are right now.”

Extending a hand in “love” to combat racism? Forgetting about the past as much as we can? Good luck with that, Common.

Common’s naïve rhetoric presents many obvious concerns, the first being that placing a band-aid on hatred and bigotry by combining happy grins with Zen vibes to birth a utopian atmosphere of racial harmony will not magically heal America’s deeply entrenched race problems. Against the growing façade of a post-racial society, Common has seemingly adapted a less-than-threatening outlook on social issues in an attempt to assimilate into mainstream Hollywood, thus presenting himself as more acceptable amongst white audiences.

As fans look back at the brilliance of Be, and reminisce on the ways in which the Windy City native once blessed us with skillfully crafted lyrical portraits of inner-city blues, clenched fists and the ongoing quest towards Black equality, many of us sit, hoping and waiting, that the Common we once knew will one day soon return.

Shelby Jefferson is a blossoming journalist, and currently works as a staff reporter for a Michigan-based community newspaper. As a radical intellectual, writer, poet and pop culture junkie, she frequently uses her articles to analyze and present a broad spectrum of themes including race and representation in television/music/film/media, contemporary arts and culture, race and gender identity in sports and social justice issues in the United States.