It was 60 years ago that Collins made such a historic achievement and yet no other Black ballerina has been able to boast the same accomplishment.

During a time when racism in America barred Black girls from even attending the same ballet classes as their white counterparts, Collins and her mother refused to let her talent go unnoticed.

Doors were slammed shut, noses were turned up and hopes were hurled to the ground, but Collins never stopped prancing forward.

When she was still just a young girl, her mother struck a deal with a ballet instructor that would forever change Collins’ life.

Her mother would sew costumes for the renowned teacher in exchange for private lessons for Collins.

Even in the era of racial segregation, her teacher couldn’t help but admire the Black girl’s talent in an art form that had long been dominated by pale faces.

By 1921 Collins and her family bid farewell to New Orleans and headed to the West Coast in hopes that the new region would come with fewer barriers for a talented Black girl. Their hopes, however, were quickly tainted by the realities of racism’s far-reaching grasp.

While moving out west did provide Collins with an amazing opportunity, it came with racist conditions that Collins refused to accept.

At the age of 15, Collins was accepted into the prestigious Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo but only if she agreed to paint and powder her skin white.

“I thought talent mattered, not skin color,” Collins wrote of her experience.

It marked the time in her soon-to-be flourishing career that she came face-to-face with the true ugliness of racism.

Despite the fact that she was nothing short of a dancing protégé and one of the most graceful dancers to ever don a tutu, her skin color was enough to leave the dancing world’s elite hesitant to give her a chance.

Eventually, however, her time would come.

She got her chance to dance in the company of greats like Lester Horton and choreographer Katherine Dunham who specialized in stunning African, Caribbean and classical pastiches.

Even the atrocities of racism couldn’t keep Collins’ talent from being recognized, although it drastically slowed her climb to stardom.

She was 32-years-old when she made a career-changing move to New York. Around that age many ballerinas are contemplating retirement and have already sown the triumphant peaks of success.

Around this time, critics finally heralded her as a stunning dancer but she still hadn’t earned the types of opportunities that her white counterparts were offered on a consistent basis.

“She could, and probably would, stop a Broadway show in its tracks,” one critic wrote of Collins.

Eventually, just the right choreographer would indeed be left motionless after witnessing Collins in action.

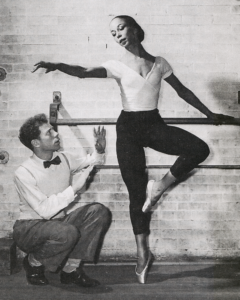

Zachary Solov, the Metropolitan Opera’s choreographer, hired Collins in 1951. That hiring decision made history and catapulted Collins from a protégé to a groundbreaking ballet icon.

She danced at the Met for three years, starring in Aida, Carmen, La Gioconda and Samson and Delilah.

It was here that Collins was able to escape the grasps of racism for a short while. Her dressing room was on the same floor as the other dancers during a time when performers were typically being segregated by race.

Black performers were rarely even allowed on stage with white performers across all art forms so Collins’ situation was truly unique for her time.

Unfortunately, it was only at the Met that this progressive set up was evident.

On the road, other facilities in the South refused to let Collins join the white performers on the stage and an understudy would fill her place.

While she continued choreographing works throughout the early ’70s, she eventually left the dance world all together and retired to a life of painting before she passed away in 2003.

Her story has inspired young Black girls today who hope to one day have their own chance to embrace their body’s own movements as a form of art on a prestigious stage.

With dancers like Misty Copeland, who was also inspired by Collins, receiving national recognition for their talent despite the color of their skin there is hope that more dancers of color will be able to change the face of ballet.

“Picture a ballerina in a tutu and toe shoes. What does she look like,” Misty Copeland writes of the racial disparities in ballet. “Most would say she is a fragile-limbed pixie with flaxen hair and ivory skin. … Ballet isn’t just about ability or strength. You must also look the part.”

That biting truth about the grasp racial biases still have on the world of ballet is exactly why no other Black girl has been able to truly follow in Collins footsteps and why Copeland is only the third Black female soloist to join the American Ballet Theatre.

There are six decades between Collins’ retirement and Copeland’s historic achievement and yet it seems as if the landscape these two women faced is stunningly similar.