A crucial environmental case is currently being deliberated by the U.S. Supreme Court that could potentially save thousands of lives in the Black community and determine the state of the community’s health for generations to come.

While the case hasn’t gotten much attention from the mainstream media, it is one of the most important that the court has heard in years directly affecting the plight of Black people.

The federal Environmental Protection Agency in 2011 issued new guidelines, called the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards (MATS), for the first time ever limiting the toxic air pollution that coal- and oil-fueled power plants were allowed to emit. It required these plants to reduce emissions by upgrading their facilities to more public health-friendly systems.

While few plants run on oil, coal plants provide the U.S. with nearly half of its electricity.

But these regulations did not go over well with the power industry. Plants argue that the rules impose an unfair financial burden on them and hamper their ability to turn a profit. It’s a familiar complaint from industry whenever they’re hit with a new requirement.

Why is this of such import to the Black community?

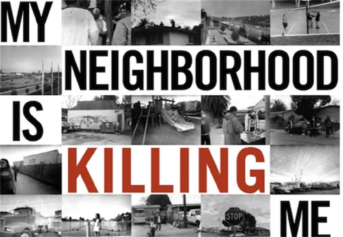

Because these coal-powered plants spew extremely poisonous toxins of pollutants into the air every day that cause diseases and conditions like cancer, chronic heart conditions, ADD/ADHD, and respiratory diseases ranging from asthma to lung cancer in the surrounding communities.

Not only that, 68 percent of the 42 million African-Americans in this country live within 30 miles of one of these coal-fire plants.

Yes, you read that correctly.

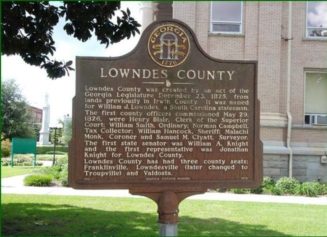

It is not a coincidence. For a long list of reasons that mostly come back to racism and exploitation, these dangerous plants are far more likely to be built in poor areas mostly populated by Black and Hispanic people.

Black children are the most likely to be exposed to mercury, in particular, which is a neurotoxin that after long-term exposure can cause fetal birth defects, brain damage or delayed development, emotional disturbances and psychotic reactions, and more.

Jacqui Patterson, director of the NAACP Environmental and Climate Justice Program, which is backing the EPA in the case before the Supreme Court, said that African-American children are two to three times as likely to miss school, be hospitalized, or die from asthma attacks than White children.

“For us, it’s very much a civil rights issue if certain communities are being disproportionately impacted by the pollutants that come from these coal plants,” she said, according to a story by Jazelle Hunt, Washington Correspondent for the NNPA, the Black press organization.

To make its case, the NAACP referred to a report it issued called “Coal Blooded: Putting Profits Before People.” The organization assigned a grade and rank to nearly 400 coal plants around the nation, in addition to listing the worst plants, the worst companies and the toll these plants take on the surrounding communities.

According to the report, four million people live within three miles of the 75 worst plants, and nearly 53 percent of them are Black and brown.

The five plants with the worst environmental justice performance were: Crawford Gen. Station and Fisk Gen. Station in Chicago; Hudson Gen. Station in Jersey City, N.J.; Valley Power Plant in Milwaukee, Wis.; and State Line Plant in Hammond, Ind.

The most failing plants are in the states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Virginia, and Colorado.

In addition, the Black community is in for a double whammy—after the pollutants do their damage and alter the climate, then Black communities bear the worst effects of climate change.

“Indeed, Hurricane Katrina and the tornadoes in Pratt City, AL have already vividly demonstrated that the shifts in weather patterns caused by climate change disproportionately affect African Americans and other communities of color in the United States—which is a particularly bitter irony, given that the average African American household emits 20 percent less [carbon dioxide] per year than the average white American household,” the report states. “The six states with the largest proportion of African-Americans are all in the Atlantic hurricane zone, and all are expected to experience more severe storms as a consequence of global warming.”

If the EPA regulations are allowed by the Supreme Court to take effect, EarthJustice, a nonprofit environmental justice organization, estimates that they would reduce mercury emissions by 75 percent, preventing up to 11,000 premature deaths, nearly 5,000 heart attacks, 130,000 asthma attacks, and more than 540,000 missed work days each year.

After hearing oral arguments for 90 minutes last week on the case, known as National Mining Association v. Environmental Protection Agency, the Supreme Court is expected to issue a decision by summer.