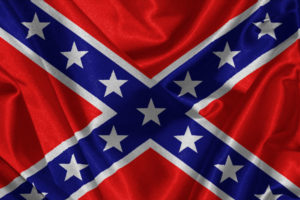

Venues across the land have been holding events this week to commemorate Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender on April 9, 1865, to Union Gen. Ulysses Grant at the Battle of Appomattox Court House in Virginia, effectively ending the Civil War. But even as these events transpire, the Supreme Court is currently deliberating whether Texans should be able to put an image of the Confederate flag on their license plates.

The raging emotions over the Civil War and slavery are ever-present in the American town square, forcing us all to take sides just like they did for our ancestors 150 years ago.

While African-Americans continue to be marginalized economically, socially and politically in the U.S. (Barack Obama notwithstanding), it is no coincidence that the most consequential event in American history, the Civil War, was undertaken over the desire of white people to continue to own the bodies of Black people. Northerners and Southerners alike had exploited Black bodies for generations before the war to create the global juggernaut that became American capitalism—they were having a hard time swallowing the notion that someday they might actually have to pay their laborers.

Indeed, the institution of slavery hovers over the nation’s history like a cyclone, altering everything in its path. There may be those who try to make dubious claims that the war was about “states’ rights” and that the Confederate flag is merely an innocuous symbol of Southern heritage, but for an enormous swath of our nation’s history, most every political, moral and economic argument was about slavery. Every time the nation considered expanding westward, the North and the South had to engage in nasty debate about whether the new states would allow slavery. When Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas wanted to build a railroad to span the entire continent, the North and the South had to engage in nasty debate about whether it would cross through the slave states of the South or the free states of the North—since it would significantly enhance the property values of every place it would touch.

Even when the Democrats gathered in 1860 for their national convention, on the eve of the war’s commencement, slavery was really the only issue on the table, according to historian Edward Baptist in his new book, The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism. In fact, as the arguments waged between Northern and Southern Democrats, one Northerner said, “ruling niggers all their lives, [they] thought they could rule white men just the same.”

The Democrats even invoked race in their name for the new Republican Party—they called them “Black Republicans,” according to Baptist, because of their opposition to slavery.

In the arguments over whether the South should secede, white Southerners made claims that foretold the destructive role that race would come to play in the evolutionary growth of American society. This is what an emissary from Mississippi argued to his Georgia counterparts, according to Baptist:

“Not only would emancipation mean that non-planters would lose the chance to move up in the world—a chance that ownership of even one slave could represent. Worse, the everyday distinctions that gave status to all whites, especially men, would vanish. Lincoln’s victory left only once choice. Secede, or your neighbor’s field ‘hand’ will marry your daughter. Secede, or offer up your ‘wives and daughters to pollution and violation to gratify the lust of half-civilized Africans.’ Republican domination, the emissary concluded, meant a ‘saturnalia of blood, a war of extermination’ that would lead to the destruction of the white people by ‘assassinations and amalgamation or rape.'”

In that one speech, the Mississippian established the tone and the underlying fears of race relations for the next 150 years. He even forebodingly predicted the motivations of the police forces that the white communities would form in the coming years, to engage the Black community in this “war of extermination” and protect the purity of white women from the “lust of half-civilized Africans.”

The Civil War was an incredibly brutal and destructive campaign that ultimately took the lives of 700,000 Americans. And it should never be forgotten how much Black soldiers contributed to the war effort—40,000 Black soldiers died in the war.

Baptist writes that in the days following the April 9 surrender at Appomattox in Virginia, when Union soldiers came upon Southern plantation after plantation, freeing Black people who were still enslaved in many of these places, many of the Black people turned around and cursed out their former enslavers, unleashing generations of pent up rage. Some of the enslavers committed suicide.

Historians say it was President Lincoln’s speech after the war about extending the vote to Black people that incited John Wilkes Booth to decide to kill Lincoln on April 14, 1865. It was Good Friday.

“Abraham Lincoln was either the last casualty of the Civil War or one of the first of a long civil rights movement that is not yet over,” Baptist writes. “He was succeeded by his vice president, Andrew Johnson, who was unfortunately an alcoholic racist bent on undermining emancipation. Johnson spent the summer signaling to southern whites that they could build a new white supremacy that looked much like the one African-Americans had fought to end.”