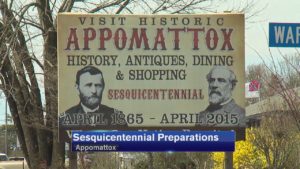

An incredibly compelling funeral is taking place this week in Appomattox, Va., a full 150 years after the deceased passed away. It is the funeral for Hannah Reynolds, a former enslaved Black woman who was the only civilian to die at the Battle of Appomattox Court House, when Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union Gen. Ulysses Grant, effectively ending the Civil War.

Reynolds’ story is so heartrending because it was always assumed that she died on April 9, 1865, when a cannonball ripped through the house of her master, taking her life. That would have meant she passed away just hours before the end of the war would have made her a free woman.

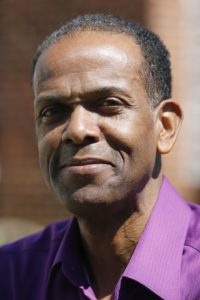

But due to the sleuthing work of a local genealogist, Pastor Alfred L. Jones III, a significant piece of information was recently discovered about Reynolds: She didn’t die until three days after she was hit by the cannonball, meaning she actually did die a free woman.

Reynolds is a key figure in the ceremonies taking place this week to mark Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Virginia. They will be capped off Friday night with an actual funeral service for Reynolds featuring a eulogy in “period language” delivered over a plain wooden coffin that will represent Reynolds’ body, according to the Associated Press.

It is a tableau that will be sure to move to tears many people in the audience tomorrow night.

For months, Jones dug in, trying to find more information on Reynolds. Then one day he came across her name on a death registry at Jones Memorial Library, a private research library in Lynchburg.

“That was just like I struck gold,” he told the AP, when he saw that the date of her death was listed as April 12, 1865 — not three days earlier, as was long believed.

And there was more: her slaveholder, Dr. Coleman, in a rare gesture, listed himself as “former owner.”

“I think he realized the historical significance of that,” Jones said. “Obviously it meant something to him.”

Jones said he wants to believe this woman who had been enslaved for 60 years was able to regain consciousness over those final three days long enough to realize she would die a free person.

“I just imagine, in my mind, somebody whispering, ‘You’re free, you’re free, you’re free,'” Jones said.