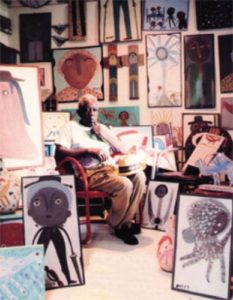

His flat, unconventional portraits of birds and houses seem delightfully whimsical and his self-proclaimed “nasty” works portraying smiling caricatures of naked women come across as the naughty misdeed of a child-like spirit rather than an erotic attempt to awake the senses.

Everything about his creations seem to evoke feelings of joy and exude happiness.

It’s for this very reason that many may find it hard to believe that it was tragedy that gave birth to one of the world’s most loved and celebrated “outsider” artists.

Tolliver, like many artists, sought refuge in art in the wake of tragedy.

The father of 13 children, two of whom died in infancy, was left handicapped after a half-ton of marble crushed him as he swept up the delivery area of a furniture company.

Before Tolliver turned to art, his life was leading him down a path that connected one odd job to the next.

Cleaning the space in the McLendon Furniture Company was supposed to be just another part-time gig but it turned out to be the catalyst that changed Tolliver’s life forever.

With his left ankle shattered and both of his legs severely damaged, the soon-to-be artistic maverick would need assistance to walk for the rest of his life.

The accident sent him into a downward spiral that tossed him into the belly of alcoholism and dragged him through the dark abyss of depression.

During a time when Tolliver felt he had little else to look forward to, art emerged as a beacon of hope and a much-needed escape.

It isn’t clear if Tolliver was already dabbling in creative projects prior to his life-changing injury but the Encyclopedia of Alabama notes that this was the fire that ignited his artistic career even though the former handyman didn’t even realize it.

Tolliver never painted to be an artist. He sold his paintings, but it was never really about the profit. After all, he often let the paintings go for just $1 or $2 or even a decent sized bag of rice.

He never boasted his artistic abilities and even refused an opportunity to take art classes in order to perfect certain techniques.

Raymond McLendon offered to pay for Tolliver to take the art classes but what McLendon hadn’t realized just yet was that Tolliver’s journey was one of personal, intimate emotion being poured into his work. The type of creations he hoped to produce couldn’t come from trained technique or textbook lessons.

Technicially speaking, everything about Tolliver’s works were “wrong.”

He never cleaned his brushes, causing the colors of his subjects to swirl together and blur what would have been defining lines. In a field that admired depth and multiple dimensions, he created a collection of flat pieces that blatantly ignored spatial concepts or accuracy in proportions.

In many cases the subjects of his works were misunderstood and confused because people couldn’t always agree on what exactly Tolliver was trying to create with this sporadic brush strokes and unconventional eye.

That’s perhaps what makes Tolliver’s works so special and truly representative of who he was as an artist.

“Aside from his physical disability, Tolliver was also dyslexic, leading him to experiment with turning paintings upside-down, sideways and in between,” the Huffington Post writes of Tolliver’s works. “His thorny relationship to language is also visible in his imaginative and unorthodox painting titles, like ‘Jick Jack Suzy Satisfying her own Self’ and ‘Moose Lady On Her Exercise Rack.’ “

All these traits make Tolliver one of the most memorable, lovable and easily recognizable outsider artists, a term that refers to artists who work “outside and often without knowledge of the artistic institution,” according to the Huffington Post.

Nearly a decade after losing a battle with pneumonia in 2006 at the age 86, Tolliver is still being celebrated in art exhibits today.

In May, the Tennessee Valley Museum of Art will have a posthumous exhibit titled “MoseT Would See It: Expressions Through the Life of Moses Tolliver.”

The exhibit will put 90 of his framed works, dating all the way back to the 1970s, on display.