The bill is expected to easily pass the Republican-controlled Arizona House, after which it will land on the desk of Governor Doug Ducey, a Republican.

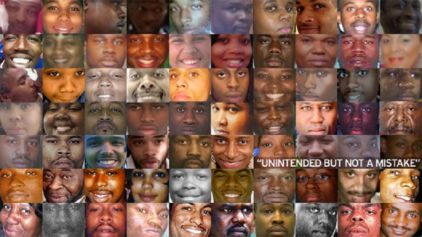

After unarmed African-Americans such as Eric Garner, Michael Brown and Tamir Rice were killed by police, an outcry immediately was raised in the public for the officer’s name. If Black protesters in these cases were forced to wait for two months for law enforcement to give them a name, the outrage would be extreme.

But Arizona lawmakers say the law would be intended to protect the officers. The bill’s supporters claim that officers have gotten death threats after deadly force incidents even if the officer was not ultimately charged or disciplined and the killing was ruled an accident. It should be pointed out, however, that officers getting charged is an extremely rare occurrence.

“This is about protecting the welfare of an officer who is not a suspect,” said Levi Bolton, a retired Phoenix police officer and executive director of the 14,000-member Arizona Police Association, which backed the bill. “You still get the ‘when’, the ‘where’ and the ‘how’ if we know it – you just don’t get the ‘who.'”

“We don’t usually talk about it, but threats are real and people talk about executing police officers – these are the kind of things that can be abated by having a cooling-off period,” Bolton added.

The state senate actually approved a 90-day wait, but it was chopped down to 60 days after further debate.

Phoenix lawyer David Bodney, who specializes in free speech and public records law, criticized the bill’s lack of transparency and said it was counterproductive.

“What if the officer has a history of use of deadly force, or his or her supervisor has done too little to reduce the risk of a recurring problem? And secrecy encourages speculation and leads to error,” he said, adding that there were already measures in place to protect an officer and his or her family before a name is released.

“In the digital age, the identity will probably come out anyway, which would leave the police department looking rather silly,” he said.

The legislature added the following exceptions: if the officer is charged with a crime or if the officer chooses to disclose his or her identity, or if the name is released by family members in situations where the officer was also killed.

The house has actually added an amendment to the bill—also withholding the names of officers against whom disciplinary action has been taken.

In the eyes of the Arizona legislature, police officers should be protected from the public at all costs—even when they do wrong.