Reports indicate several parents were outraged when their eighth-grade students came home from River Trail Middle School with packets about the Civil War and Reconstruction that included what some considered to be a racially insensitive political cartoon.

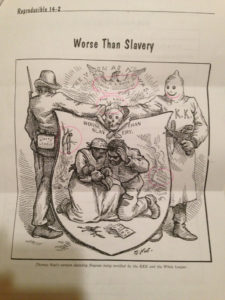

The drawing featured a caption that read “Worse Than Slavery” and shows a Ku Klux Klan member shaking hands with a White League member. Between them, a Black family is seen holding a baby and a lynching is off in the distance behind them.

“This is a white man’s government,” is also displayed on the cartoon.

Another worksheet in the packet explained that the children’s assignment was to explain the symbolism that was present in the drawing.

Only one class received the controversial packet.

The school’s spokesperson, Susan Hale, admitted that perhaps better context was needed for the cartoon but believed that this was an important learning experience.

“The political cartoon was included in a packet of class materials about the Civil War and Reconstruction,” Hale said in a public statement. “In retrospect, we regret that it was not shared with students in a more culturally sensitive way and that families were not given proper context for the material. We are reviewing the situation so we can learn from it.”

One parent, Enzie Glass, said the message was simple—the comic was too much for its young audience.

“Let’s say if this was a sexual health class, you wouldn’t go and show the kids a porno movie,” Glass said.

The cartoon is actually a historical piece, not just in its content but in its own existence.

It was drawn by Thomas Nast, one of the first political cartoonists, and its purpose was to shock Harper’s Weekly readers into realizing that just because slavery was disbanded, the Black community was still being oppressed and massacred.

The history behind the piece and the accuracy of its actual message is something parents didn’t argue against, but some insisted that it was simply too much for their eighth grade student.

That’s were the conversation seems to get complicated.

By the time students reach the ninth grade, their first year of high school, life’s tougher questions start rearing their heads.

Students are asked to think about collegiate plans, future careers and start considering the serious life choices that can truly impact the trajectory of their lives. At this point, one might argue, it’s essential that students have a thorough understanding of their history and culture.

For a Black student, that certainly means understanding slavery.

Not the white-washed, incomplete, often inaccurate, “oops my bad” version of slavery that is too frequently taught in public schools, but rather the full spectrum of slavery and its long-lasting impact on America’s economy and the Black community.

As graphic of a reality that may be, it’s an essential part of the history.

After all, the idea that slavery and its aftermath “wasn’t that bad” is exactly what is still driving many racist attitudes today.

If Black children aren’t in some way exposed to the reality of their history while in middle school, when they are entering their teens, then when do the conversations begin? How should they take place in a school setting? Should they take place in a school setting? And when are white students going to be taught this crucial information if they don’t get it at school?

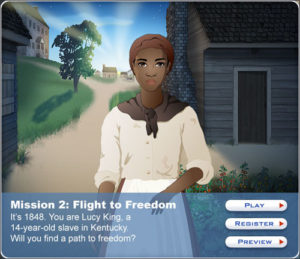

These are the same questions that drove controversy surrounding a video game that simulated what life was like for a young enslaved Black girl.

Parents weren’t happy about the emotionally charged game that forced children to make difficult decisions as they took on the role of a 14-year-old girl in slavery by the name of Lucy King.

Yet again, parents were divided about the approach.

Some believed it was exactly what the students needed—a more interactive look at how dark slavery really was.

Other parents, however, just weren’t comfortable with the idea.

“I felt the pit of my stomach drop,” said one parent opposed to the video game. “The idea of putting children in that place, thinking of my children….I just said: ‘This is where I draw the line. This is not OK.’ “

So as more schools begin trying new methods to introducing young students to the not so pretty picture of slavery, perhaps now is the time for Black parents to realize that conversations about slavery don’t need to wait until college and beyond.

How that conversation needs to take place in the classroom is still an open discussion, but one that needs to be explored in a country where 12-years-old isn’t too young to get gunned down police. It might not be such a bad idea to have young Black students exposed to America’s racist roots at an early age.