In the wake of police killings of unarmed Black men in too many places across the country, there was a loud call for police officers to start wearing body cameras to capture on video all of their interactions with the public. But in the first six months that police officers in Denver wore the body cams, they failed to record about three-quarters of the use-of-force incidents in which they were involved.

These results should raise serious doubts about body cameras being a solution to the brutalization of African-Americans by the police. If a bad officer wants to engage in bad behavior, as the Denver experiment revealed, he’s likely not going to turn on his camera to capture it all for public consumption.

Though there have been many reasons to conclude that body cameras may not be the panacea that the public was hoping for, President Obama announced in December in the midst of nationwide protests over Ferguson that he would ask Congress for $75 million over the next three years to subsidize the purchase of up to 50,000 body cameras to outfit the nation’s police.

More than 150,000 people went online to sign a White House petition urging the president to “create a law” that would force all officers to wear body cameras. The police departments in cities like Los Angeles and New York announced that they were equipping some or all of their officers with the cameras.

Much of the evidence of their effectiveness comes from the experience of Rialto, California, where the use of force by officers declined 60 percent and citizen complaints against police fell by 88 percent in the first year they used the cameras.

But it appears that all this excitement, even on behalf of the commander-in-chief, was probably quite premature. Like everything else that involves the actions and decision-making of individuals, the system is only going to be as good as the people employing it. As Denver’s experience shows, if officers don’t want to comply, they render body cameras useless.

The case of Eric Garner in New York introduced the first bit of skepticism into the discussion. After all, if a police officer still isn’t charged after he’s captured killing a man on camera, what good can come from body cam footage?

In Seattle, an incredibly expensive video records request in November may have brought plans for police body cameras to a screeching halt, just as the Seattle Police Department was preparing to have about 1,000 officers suited up with body cameras by 2016.

An anonymous computer programmer who runs a YouTube channel dedicated to revealing 911 calls, surveillance and police videos placed a request for daily updates on the police videos. But the department claims it doesn’t have enough money or staff to fulfill such a request.

And Missouri has shoved into the public sphere one of the most important discussions surrounding the cameras: Who controls the footage?

A Missouri state legislator introduced a bill last Month to ban the public from having access to the body camera footage. The idea is also supported by Missouri’s Democratic Attorney General Chris Koster, who released a report in February that proposed closing the public’s access to the camera footage under the state’s Sunshine Law. He said the footage should be available only to people who are investigating a civil lawsuit about the incident or to others by court order

In Denver, there were 80 documented cases of use-of-force during the six months from June to December 2014, when about 100 officers were testing the body cams. These incidents included officers punching, “tasing” or using batons on suspects. But of the 80, just 21 — or 26 percent — were recorded, according to a report from the city’s Office of the Independent Monitor, Nicholas E. Mitchell,.

The report said the incidents were not recorded by the officers either because the encounters escalated too quickly to activate them, the equipment malfunctioned or there weren’t enough cameras to go around. But the monitor claimed that in a number of those cases, officers did have time to activate their devices but simply didn’t do it—even though it was a stringent requirement.

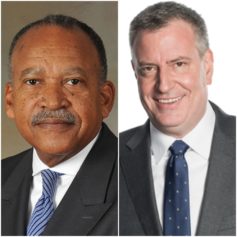

Denver Mayor Michael B. Hancock and Police Chief Robert White, who are both African-American, have said they want to expand the body cam program so that every officer on the force is equipped with one.

In his report, the independent monitor said officers should be trained on the importance of activating the body cameras before initiating contact with people, and keeping them on until the end of the encounter.

He also recommended that the Denver Police Department amend its policies to require officers to inform people that they are being recorded.