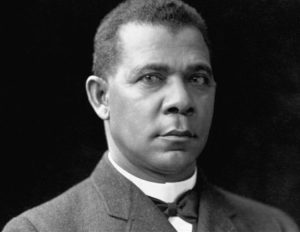

That blemish on Washington’s record of good should not hold up against his significant work in educating Black people at a time when that was not easily accessible.

He overcame a lot to become the first leader of Tuskegee Institute, a feat that deserves the ultimate respect. Washington was born enslaved in Virginia in 1856 and battled his way to become a professor at one of the earliest universities for Black people.

At the age of 16, Washington went on to study at Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, now Hampton University, in Virginia. There he became a star student, catching the attention of Hampton’s founder, Gen. Samuel C. Armstrong.

When the founders of Tuskegee sought a white president to open the school, they asked for a recommendation from Armstrong. He instead suggested Washington.

So with 30 students, Tuskegee began in 1881 in a rundown church and shanty. Students held umbrellas over Washington as he lectured so he would not get wet, and the buildings were rundown. But Washington pushed on.

He served multiple roles that first year, teaching, managing the school and working as a liaison between it and Black and white communities. His commitment paid off, as he was able to secure enough loans and donations to purchase a 100-acre plantation and construct new buildings.

Washington instituted that each student — in addition to academic basics like history, English and math — take up a vocational trade to learn. Women studied housekeeping and sewing, while men worked in areas such as farming, carpentry and brickmaking.

He regularly held “Sunday Evening Talks,” which he used to reinforce his views on education.

“When you speak to the average person about labor, industrial work, especially, he gets the idea at once that you are opposed to his head’s being educated — that you simply want to put him to work,” he said during one 1895 evening talk, according to NPR.

“Anybody who knows anything about industrial education, knows that it teaches a person just the opposite — how not to work. It teaches him to make water work for him, to make air, steam and all the forces of nature work for him. That is what is meant by industrial education.”

The Tuskegee Institute attracted attention across the country. Washington embraced all students, refusing to turn anyone away, so the school grew quickly and reached approximately 1,000 students by the early 1900s. This was more than all of the white public college students in Alabama combined, said professor Robert Norrell, author of “Up From History: The Life of Booker T. Washington.”

“[Washington] educated a lot of people,” Norrell said to NPR. “He created an institution that became a powerful symbol of Black competence, of Black success, of Black achievement.”

This was an important message to send at the time, Norrell said. And Washington’s willingness to work within the confines of America’s oppressive system contributed to this success.

But Washington focused on gradual success, something that put him at odds with other Black leaders, most notably W.E.B. Du Bois, who wanted more direct, immediate action. Washington pushed for vocational training. Du Bois favored collegiate education.

“Education must not simply teach work — it must teach Life,” Du Bois famously said.

Washington’s approach was practical for the masses, the children of former enslaved people. Du Bois focused on advancing the “talented tenth,” an exceptional group of African-Americans who would uplift the Black community.

The debate will rage on about who was right. The fact is Washington built a legacy of helping Blacks who needed help. How can that not be a good thing?