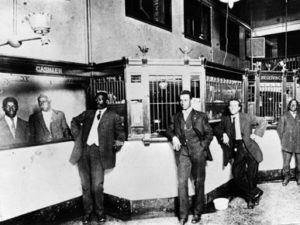

Less than a month before he was assassinated, Abraham Lincoln signed the Freedman’s Bank Act that authorized the organization of a national bank for Black people recently freed from slavery—a grand notion in theory, but one that ended up costing many unsuspecting African-Americans their life savings.

The Freedman’s Bank grew rapidly, with 34 branches opening in 10 years with more than $3 million in assets. But on June 26, 1874, the bank closed amid controversy.

Six months prior to closing, the United States Congress approved the banking institution. A white northerner named John W. Alvord was the bank’s first president. He was a former minister and attaché to General William Tecumseh Sherman during the Civil War.

He traveled throughout the South recruiting Blacks using endorsements from General OO Howard (the commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau) as an enticement. Alvord told them, “As an order from Howard … Negro soldiers should deposit their bounty money with him.”

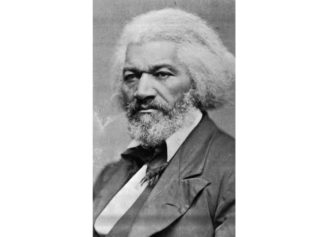

A bank using the savings and income of Black depositors to advance the economic fortunes of whites was a major paradox—and a blueprint for swindling. Sure enough, corruption followed and the bank’s management was replaced with a variety of Black elites, most notably Frederick Douglass, who was appointed to head the bank in March of 1874.

These changes did not prevent the bank’s closing, with Douglass later describing the experience as being unwittingly “married to a corpse.”

By 1900 only $1,638,259.49, or 62 percent of the total amount of deposits prior to the bank’s failure, had been paid back to Black depositors. Deposits worth some $22 million of Black people’s money in today’s dollars were gone. In the end, most Black depositors lost their savings, receiving little to no money back from the bank or the federal government.

Today, there are just 19 Black-owned banks in the country, and almost 70 percent of them are in dire financial straits.

Vibrant financial institutions run by Black people are critical to fabric of communities. WEB DuBois and Booker T Washington did not agree on most, but they thought similarly about the pain the loss of Black banks delivered.

DuBois said: “Then in one sad day came the crash—all the hard-earned dollars of the freedmen disappeared; but that was the least of the loss—all the faith in saving went too, and much of the faith in men; and that was a loss that a nation which to-day sneers at Negro shiftlessness has never yet made good.”

Added Washington: “When they found out that they had lost, or been swindled out of all their savings, they lost faith in savings banks, and it was a long time after this before it was possible to mention a savings bank for Negroes without some reference being made to the disaster of [the Freedmen’s Bank].”