If the experiences of Kalamazoo, Mich., are any indication, two things need to happen for there to be significant progress in the police department’s relationship with the African-American community: the police need to acknowledge that some implicit bias is at play in the way officers treat Black residents; and officers have to embrace the idea that they need to be warmer and more personable in their interactions with Black residents.

Both of these things are occurring in Kalamazoo and, while some young African-Americans in the city still say they don’t trust the police, crime has dropped even while the police conduct far fewer traffic stops than they did before the advent of this softer, gentler approach.

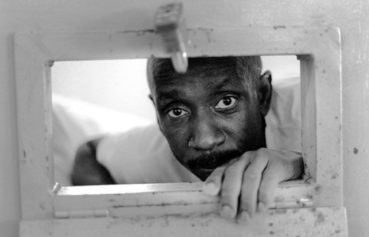

At a time when the hostility between police and African-Americans is the focus of a national debate after a string of high-profile police killings of unarmed Black men, the methods being employed in Kalamazoo perhaps might be instructive to police departments across the nation.

The event that launched this drastic reform in the police department was the release of a yearlong study that found the Kalamazoo police were racially profiling residents, according to a story about the department by Al Jazeera America. Conducted by Lamberth Consulting, a company whose specialty is studying racial profiling, police in Kalamazoo stopped Black motorists more than twice as often as whites. And even more damning, although many more Black were searched, handcuffed and arrested, whites in this city of 75,000 were more likely to be found with contraband like guns and drugs. Lamberth looked at police stops at 12 different locations from March 2012 to March 2013.

The entire force was shocked by the results, according to Public Safety Chief Jeff Hadley, who actually commissioned the study.

“It kind of takes your breath away,” he told Al Jazeera America. “But what do you do? Do you sit there and act like a deer in headlights? Do you dismiss the study that you asked for?”

The chief instituted a number of changes, including consulting with renown sociologist Lewis Walker, founder of Western Michigan University’s Walker Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnic Relations. Walker got the officers to understand implicit bias—beliefs that operate outside your conscious awareness.

“It is important to me that police officers understand implicit bias. And not fight it, but understand that we are all socialized. This country socializes us to be biased,” Walker told Al Jazeera America. “It is not just a white thing. It’s an American thing.

Hadley instituted mandatory racial bias training for Kalamazoo officers and also ordered that they document probable cause for every suspect they search. He also forced them to interact with residents by doing things such as going door-to-door and just chatting.

While more than 20 percent of Kalamazoo’s residents are black, only 21 of the 212 public safety officers are African-American–10 percent of the force.

Jacob Pinney-Johnson, 27, a Kalamazoo native, said the racial profiling numbers didn’t shock the Black community.

“Most people I talked to were not surprised,” said Pinney-Johnson, who told Al Jazeera he still didn’t trust the police. “I don’t think it was necessarily new news.”

When Al Jazeera America accompanied Sgt. Scott Boling and a fellow officer on a foot patrol in early February, they saw the new approach in action. The officers went door-to-door, talking to people. At one point, they were even invited inside the house by a man who gave them tips on drug activity at a nearby location.

“He gave us specific information about an individual and where this person tends to hide guns, recent shots fired, along with drug activities,” Boling said. “And that only comes when you build trust with the community. I think that’s huge.”

Boling told Al Jazeera he can even see how overly aggressive policing can backfire.

“When you blanket an area with strict enforcement, it’s unfortunate but there some people that are affected that aren’t causing problems,” he said.

Thus far, even while making far fewer traffic stops, the chief says overall crime has dropped by 7 percent.

Walker gives the force a great deal of credit for the change.

“I don’t think people understand the enormity of that job, of changing the situation,” he said. “A lot of us would like to see things changed overnight. This won’t happen… We didn’t get here overnight. We’re talking about decades, many, many years, of differential police activity.”

Hadley said they still have a ways to go.

“I’m not going to sit here and paint some picture like every interaction is going to be Andy and Barney in Mayberry,” he said, referring to the classic sitcom “The Andy Griffith Show.” “We deal with some complex stuff. We have to listen. We have to pay attention. We have to look ahead, down the road, and see what’s the best way we can achieve crime reduction at the same time maintaining the relationship with the community.”