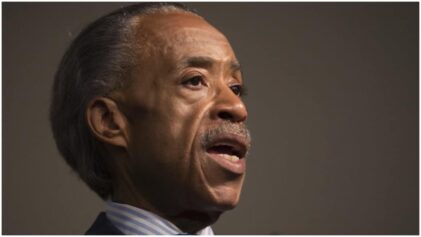

Al Sharpton’s place in the movement for justice is strange at worst, enigmatic at best, especially for someone who has been in the civil rights trenches for so long and committed so much.

For all his in-your-face, down-for-the-African-American-cause work he has done for decades, Sharpton remains dogged by intense speculation that questions his motives and character. These contradictory dynamics collide to make him, at once, a polarizing and galvanizing figure.

In the end, though, the clashes of perspectives on the man dilute what good he has done and, ultimately, his ability to fully function as an agent for change.

Already this week, Sharpton is in the middle of two controversies that provide further evidence of his unique ability to rouse suspicion and support.

The National Association of African-American Owned Media has included Sharpton and his television show in a $20 billion lawsuit against Comcast that alleges it discriminates against Black-owned media companies. It cites Sharpton as being bought off for $3.8 million by Comcast to not speak out against racist practices within the company.

Comcast, on the verge of completing a merger with Time Warner that will create the largest pay cable distributor in the country, issued a statement to The Hollywood Reporter, saying, “We do not generally comment on pending litigation, but this complaint represents nothing more than a string of inflammatory, inaccurate, and unsupported allegations.”

Sharpton offered that he “welcomes the opportunity to answer the frivolous allegations.”

He also had to address a story in which Erica Snipes said Sharpton was about money as much as he was about helping. Snipes is the daughter of Eric Garner, who was killed in a chokehold by a New York police officer on Staten Island, a case that gained national attention because it was caught on tape and the officer still was not indicted.

Project Veritas, a controversial conservative activist group founded by James O’Keefe, secretly recorded conversations with Snipes and community leaders involved in the Ferguson, Missouri case.

In the video, Snipes is questioned by a mole secretly recording her.

“You think Al Sharpton is kind of like a crook in a sense?” the investigator is heard asking Garner’s oldest daughter.

“He’s about this,” Snipes replies, rubbing her fingers together.

“He’s about money with you?” the undercover asks.

“Yeah,” Snipes responds.

Snipes later complains that a NAN supporter, Cynthia Davis, badgered her about handing out flyers without Sharpton’s group logo. “Instead of me, he wants his face in front,” Snipes says on the tape. “Al Sharpton paid for the funeral. She was trying to make me feel like I owe them.”

If Sharpton believed his ears, he did not reveal it. In fact, he said the opposite.

He said Project Veritas is “exploiting” Snipes and a dispute within the Garner family.

“They’re splicing and dicing stuff together,” Sharpton said of the recordings. “It was a distortion. Erica is a sincere victim. She was not trying to infer anything with me.”

Sharpton added that Snipes’ sister, Emerald, now works for his organization and that neither he nor it accepts money from the people they help.

In the same video, however, Jean Petrus of Brooklyn, comes down on Sharpton. “He knows how to make money and get money,” Petrus said. “They’re shakedown guys to me.”

But to the New York Post, Petrus said he is a “friend of Sharpton” and that “It was an entrapment situation. It’s really underhanded.”

Meanwhile, the lawsuit alleges Sharpton’s show is financed so he will not draw attention to Comcast. “Despite the notoriously low ratings that Sharpton’s show generates, Comcast has allowed Shaprton to maintain his hosting position for more than three years in exchange for Sharpton’s continued public support for Comcast on issues of diversity.”

Ironically, Comcast is one of the biggest companies with a chief diversity officer and Black Enterprise magazine has commended it for its practices, listing it as one of the 40 best companies for diversity.

The expansive lawsuit says the Africa Network is the only all Black-owned network among its channels and others use “celebrities” as front men while owned by white relatives of Comcast executives.

It adds that Comcast has a “Jim Crow” process with respect to licensing Black-owned channels, and that one Comcast executive said: “We’re not trying to create any more Bob Johnsons,” referring to the founder of Black Entertainment Television.

Sharpton’s retort, through NAN: “If in fact we were to be served, we would gladly defend our relationship with any company as well as to state on the record why we found these discriminatory accusations made by said party to be less than credible and beneath the standards that we engage in.

“As for Rev. Sharpton’s TV show ratings the numbers are clear. Rev. Sharpton’s show has the highest ratings of any 6 p.m. show in the history of the network.”