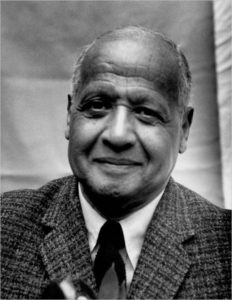

Today it is not unusual to see Black skin highlighted in modern photography, but during a time when “black appearance was under question,” iconic Black photographer Roy DeCarava embraced the use of shadows to bring out the true beauty and depth of Black skin.

The standard for photography today involves bright lighting and soft focuses that create an angelic sense about the average photograph. Even as photographers of today capture powerful protests and rallies pushing for equality in America, details of protesters are highlighted and one can usually spot the glistening of sweat on an impassioned activist’s brow.

Wide, establishing shots capture full bodies of those marching together, carrying signs and creating a clear depiction of the Black bodies moving together as a unit to complete the mission that their ancestors set out to complete so many years ago.

DeCarava’s portrayal of these powerful movements and unified forces take a different approach.

The lack of an establishing shot fails to make locations obvious and rather than forcing more light into the photographs, he was committed to pushing it out.

Close shots of Black peoples’ faces gave little context of what was happening around them, but the hues of the photos and the beauty of the shadows made it clear that something uniquely powerful was happening.

One of his most popular photographs features a close up shot of a Black woman with a stern but calm facial expression who is later revealed to be a “Mississippi Freedom Marcher.”

A shadow lies over one side of the woman’s face. It’s the type of element that modern photographers would typically try to eliminate from their subjects, but the New York-based photographer always embraced these dark elements and muted hues.

These are the types of images DeCarava uses to not only highlight the power behind the Black community but also depict the sheer beauty of his own people.

These Black faces were stunning, intense, focused and hopeful—and it was captured all in the same shot.

“His pictures all share a visual grammar of decorous mystery: a woman in a bridal gown in the empty valley of a lot, a pair of silhouetted dancers reading each other’s bodies in a cavernous hall, a solitary hand and its cuff-linked wrist emerging from the midday gloom of a taxi window,” Nigerian-American writer Teju Cole wrote of his work in an article for the NY Times. “DeCarava took photographs of white people tenderly but seldom. Black life was his greater love and steadier commitment. With his camera he tried to think through the peculiar challenge of shooting black subjects at a time when black appearance, in both senses (the way black people looked and the very presence of black people), was under question.”

By doing so, DeCarava made a dual statement—one was about the standards for technology and the other was about the standards for beauty.

Both statements, however, pressed the idea that Black skin, and therefore Black people, needed to be appreciated and admired more than it had been in both art and society.

“All technology arises out of specific social circumstances,” Cole continued. “In our time, as in previous generations, cameras and the mechanical tools of photography have rarely made it easy to photograph black skin. The dynamic range of film emulsions, for example, were generally calibrated for white skin and had limited sensitivity to brown, red or yellow skin tones.”

But DeCarava didn’t care what technology’s standards were nor did he have any interest in pulling the shadows away from his Black subjects. According to Cole, there was “confidence” in his ability to play “in the dark.”

“This confidence in ‘playing in the dark’ (to borrow a phrase of Toni Morrison’s) intensified the emotional content of DeCarava’s pictures,” Cole added. “This viewer’s eye might at first protest, seeking more conventional contrasts, wanting more obvious lightning. But, gradually, there comes an acceptance of the photograph and its subtle implications: that there’s more there than we might think at first glance, but also that when we are looking at others, we might come to the understanding that they don’t have to give themselves up to us. They are allowed to stay in the shadows if they wish.”

DeCarava passed away at the age of 89 back in 2009.

Before he passed away, however, he wrote down exactly what it was he wanted out of his work.

Rather than fame or documentaries, DeCarava wrote that he only wanted to provide a “creative expression, the kind of penetrating insight and understanding of Negroes which I believe only a Negro photographer can interpret.”