ABS Exalts Black History: Part III

ABS Exalts Black History: Part III

For the 2015 edition of Black History Month, we asked a team of talented writers and scholars to mimic the dance of the Sankofa bird and carry us back to our roots so that we may move forward.

We are presenting their efforts throughout February in an impressive array of pieces that reveal to us from whence we came and where we might want to go. There is nothing quite so edifying and necessary as African history, for its grandeur is spectacular in direct proportion to the depths of scarcity we were trained to believe in the New World. It is as essential to us as the air we breathe. We asked our writers to use as a template the words of Langston Hughes, who penned “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” as a 17-year-old boy crossing the Mississippi. Hughes uses the metaphor of the river as a way to trace the splendor of African people. Here at Atlanta Blackstar, we see these as words to live by:

I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the

flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln

went down to New Orleans, and I’ve seen its muddy

bosom turn all golden in the sunset.

I’ve known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

For Educating Black Children We Must Look to The Ancestors

By Akilah S. Richards

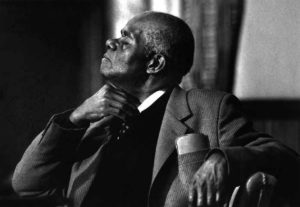

“History is a clock that people use to tell their political and cultural time of day. It is also a compass that people use to find themselves on the map of human geography. History tells a people where they have been and what they have been, where they are and what they are. Most important, history tells a people where they still must go, what they still must be. The relationship of history to the people is the same as the relationship of a mother to her child.”

– John Henrik Clarke

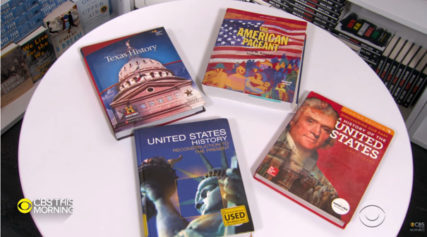

Clearly, most writers of American public school textbooks agree with Dr. Clarke, otherwise they would not have gone to such great lengths to separate Black and brown children from their histories. Many American public schools today mirror the troubled relationship between Black people and education in America. Truths are suppressed in favor of a false reality that sees white people as heroes and Black people as the resilient, but never triumphant, nation of former slaves.

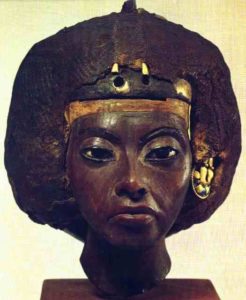

In 2015, many Black children (and their parents) remain unaware of the stolen and suppressed legacies of the well-documented brilliance of Kemet (the original name for Egypt) and other African epicenters of learning and development. We are still battling modern versions of the laws and cultural norms that found free Blacks in Louisiana, Mississippi and Virginia physically targeted (as we still are today) and economically oppressed (as we fight to continue rising from this today). Through omission of historical facts and the general white-washing of world history, we are still dealing with a version of the persistent efforts to keep Black people under-educated that enslaved Africans faced in the 1800s.

If we are to follow Dr. Clarke’s logic and place high value on knowing our history, Black parents must stop putting their child’s school in the parent role, begin to reclaim learning for ourselves and teach our children to do the same.

Unschooling: A Personal Reclamation

Our 11-year-old daughter spent nearly four years in the American public school system before my husband and I decided to unschool both our daughters. While in school, our 11-year-old was educated on a variety of topics, but she learned very little. She tested well, plus she was personable and eager to learn, so she did well academically and socially. The problem though, is that she was not learning from a Whole Child perspective. Somehow, prior to becoming a parent, I had grown to believe that schools today would teach children how to learn, not just what to remember. I was wrong.

School is a culture of its own, and the children and adults inside that school create the culture. And the culture is largely centered on a Eurocentric perspective that leaves out vital cultural and socioeconomic truths about history and today. Additionally, since public school systems must comply with county and state regulations, which are based on performance tests that determine school funding, the focus is on giving children information that shows up on tests and not necessarily in relevant, everyday life. Learning has been replaced with memorization, and the importance of each child’s learning needs and cultural narratives are, by design, irrelevant.

That may well be a necessary approach in order to serve the large numbers of students who sit in classrooms, but it is not enough for Black children. If we look back at American history and world history, we will see that it has always been Blacks ourselves who kept our history and culture as important parts of our lives. Historically, children were not sent away to learn, they learned among the adults around them until they transitioned into formal learning.

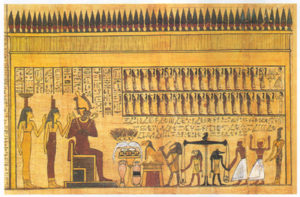

Ancient Kemet offers an example of this unschooling system out of which came many significant contributions to modern society. The contributions of these Africans include the first forms of organized writing, along with diverse and detailed studies of law, science, mathematics, engineering, philosophy and medicine, all occurring more than 5,000 years ago, before there was civilization in Europe.

The Nile Valley Civilization

The people of Kemet lived, worked and educated themselves and the world for 3,000 years. Anthropologists and Egyptologists tell of how children were largely unschooled in Kemet. They learned through the gradual acquisition of practical life skills and cultural knowledge through their elders. Young children helped with daily tasks such as feeding animals, harvesting food and assisting with pottery making. They also baked bread, brought food to workers and helped watch younger children in the community. During that time, rich cultural history and beliefs were shared organically through daily interaction with people of various ages and experiences.

Many young boys served as apprentices to learn the duties of important social and political positions like a bureaucrat or a priest. As they got older, some boys studied to become scribes to serve in temples. Girls were often trained as musicians, dancers and craftswomen. Older boys and girls both learned about property and business from a legal perspective, as inheritance was an important part of life in Kemet. No matter the end goal, school came only after knowledge of self and exploration of self through environment, culture and personal exchange.

Europeans, particularly Greek scholars, benefited from the thriving civilization’s approach to learning, but hid their sources of information, claiming the knowledge as their own. Fast-forward to the 1800s in the American South, and we’ll find that Black people were still being cut out of narratives related to learning. This time though, we were not the creators of the information, we were the ones from whom it was being kept.

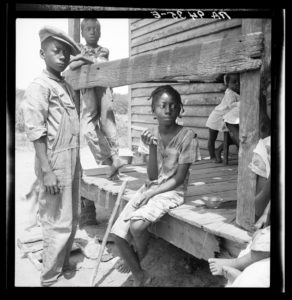

The Mississippi Delta Region

Notably, all Black people did not arrive in Mississippi as a result of slavery. As far back as the early 1700s, there was a class of Blacks of whom the vast majority were the offspring of enslaved African or African-American women and white plantation owners. These white men often made arrangements for freedom of their biracial children and their mothers. Some of these descendants inherited land, and others were granted apprenticeships that would help them secure professions. As land owners, many Blacks thrived in states like Louisiana and Mississippi.

In the early 1800s, slave societies emerged throughout Mississippi with the increased demand for cotton, tobacco and sugar. Americans pushed out Native Americans who occupied the land, freeing up space for thousands of wealthy white families to migrate to Mississippi, bringing along with them enslaved Africans. By the mid-1800s, a wealthy slave-owner class had emerged, and the majority of the Black population was now enslaved Blacks who lived on plantations with usually between 15 to 20 other enslaved Blacks.

The independent farmer was King, and his slaves were his currency. As the state continued to thrive economically, most white Mississippians attributed this to the expansion of slavery and saw it as America’s primary resource for continued economic growth. American Northerners disagreed, and resulting economic panic and disagreements among politicians caused the Southern states’ secession from the United States, prompting the Civil War.

The years following the Civil War saw freed Blacks working as laborers in various skills, and some became land owners. By the late 1860s, Blacks were participating in politics through voting, and some even held office. By 1880, due to the mass migration of Blacks to the fertile Mississippi Delta region to buy and work land, two-thirds of independent farmers in the Delta were Black. Rising resentment of the increase in Black economic freedom gave way to exorbitant voting taxes and the Jim Crow era. The brutalization and ongoing civil rights violations of free Blacks became an even more deeply embedded part of the culture of the American South.

Sixty-one years after the Brown decision, that resegregation continues today. The racial and economic duality of the area’s school system is reminiscent of the region’s past. As nonprofit financial service provider CEO Bill Bynum said of the region, “Our region still suffers from a legacy of plantation agriculture, which relied on keeping people uninformed and dependent. The vestiges of this system persist today, leaving significant gaps, opportunity gaps.”

Allowing the (Real) Past to Influence the Future

If we agree that today’s Black child, schooled or unschooled, needs to be made aware of the truth about their history in part so that they can know that their history did not begin with the transatlantic slave trade, nor was it suppressed when we landed in Jamestown, Virginia, or on the shores of a Caribbean island. When this information is omitted, our children lose sight of the legacy they came from, and the responsibility they share as the beneficiaries of those who came before us. They also lose examples of their people’s brilliance, and risk seeing themselves as less than, in comparison to the white heroes they are introduced to in their textbooks and on their TVs.

The brilliant people of Kemet knew to give their children space to explore, to question and to learn through real-life experiences relevant to their people. We must offer our children that same opportunity to self-actualize and to thrive. We do that by offering them the full truth about our history, not the one from the narrowed lens reflected in schools today. As a people, we continue to evolve and understand the layers of our past, but we must pay much more attention to the future. We, along with our children, are creating this future, but our children are the ones who will need to be prepared to thrive in whatever they are learning and creating.

Akilah S. Richards is a six-time author, digital content writer, feminist speaker, and lifestyle coach. She writes passionately about self-expression, womanhood, modern feminism, location independence and the unschooling lifestyle. Akilah is a storyteller who believes in the power of expressed personal narrative and deep self-acceptance as tools for authentic self-expression and community enrichment. Learn more about her work at AkilahSRichards.com