ABS Exalts Black History: Part II

For the 2015 edition of Black History Month, we asked a team of talented writers and scholars to mimic the dance of the Sankofa bird and carry us back to our roots so that we may move forward.

We will be presenting their efforts throughout the rest of February in an impressive array of pieces that reveal to us from whence we came and where we might want to go. There is nothing quite so edifying and necessary as African history, for its grandeur is spectacular in direct proportion to the depths of scarcity we were trained to believe in the New World. It is as essential to us as the air we breathe. We asked our writers to use as a template the words of Langston Hughes, who penned “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” as a 17-year-old boy crossing the Mississippi. Hughes uses the metaphor of the river as a way to trace the splendor of African people. Here at Atlanta Blackstar, we see these as words to live by:

I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the

flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln

went down to New Orleans, and I’ve seen its muddy

bosom turn all golden in the sunset.

I’ve known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

Sacred Waters That Nourished Black Genius, Nurtured Black Children

By Gus T. Renegade

“And next month they’ll come up to show you another trick … this negro history week. And during this one week they drown us with propaganda about negro history in Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama. Never do they take us back across the water …”

— Minister Malcolm X

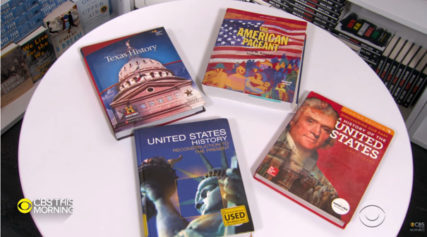

Black people are ritually subjected to a “kiddie pool” version of Black history. A begrudgingly given, teensy presentation with a splash of slavery and a few fire hoses. An exercise that does not threaten, indeed, bolsters white supremacy. Few Black people receive a comprehensive, wholesome immersion in the history of Black life on planet Earth. No chance to reconnect to ancient rivers, ancient Black souls who could contribute to our success vanquishing a common oppressor. Minister Malcolm X and Langston Hughes counsel us to insist that Black history extends before white terrorism, beyond North America.

And not for the sake of concocting a counterfeit African utopia. But for the sake of remembering Black self-sufficiency, Black accomplishments, Black possibilities.

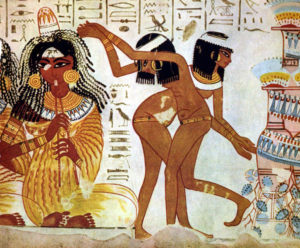

Georgia State University’s Dr. Mausiki Scales describes the Nile River as an information highway for commerce, concepts and culture of ancient African civilizations. This sacred water nourished Black architects, mathematicians and scientists whose intellectual swag offers a priceless illustration of acting Black, begging to be unleashed in their 21st century descendants. Dr. Scales describes how Egyptians constructed a solar calendar that demonstrates they “had been studying the heavens for quite some time. Some scholars would say at least 26,000 years.”

Dr. Shirley Ann Jackson is an heir. She’s the first Black female to earn a Ph.D. from Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the pioneer of caller ID and call waiting. This is but a drop in the sea of cosmic Black brilliance that can and should demand our best.

White supremacy can annihilate Black children. The millions of suspended, poorly educated, adopted, molested, abandoned Black children rarely generate investigation or a hashtag. In a time of Tamir Rice, Kendrick Johnson, Aiyana Jones, it’s deliberately difficult to conceive of a world where Black children are priceless.

K. Kia Bunseki Fu-Kiau and A. M. Lukondo-Wamba detail an alternate universe where the affirmation and protection of Black children was a cherished enterprise. “Kindezi: The Kongo Art of Babysitting” translates nourishing Black children as “the art of touching, caring for, and protecting the child’s life and the environment in which the child’s multidimensional development takes place.” The core aspect of Black history is proud Black mothers and Black fathers investing everything in Black children. If we’re the caretakers of an environment saturated with anti-Black racism, our connection, commitment to Black children—current and future—should be reflected in our unwavering opposition to racism.

Confronting injustice has been the essence of Black existence. Black people have fought consistently, globally. It’s no coincidence that Black people of the Kongo, who made the safekeeping and development of Black children an art, are reported to have instigated one of the first uprisings in North America.

“A group of Kongolese slaves broke into a storehouse about fifteen miles south of Charles Town in the colony of South Carolina. The slaves, now rebels, killed the two storekeepers and took all the guns and powder they could carry. Led by a man named either Jemmy or Cato, the rebels moved southward and killed about twenty-three white colonists.” (Shuler, 2009, p.3)

South Carolina has received a spate of recent attention for exonerating 14-year-old George Stinney and the Friendship 9, as well as the white terrorism targeting South Pointe High School. Racist vandals painted “Happy N**ger Month, KKK.” It’s doubtful the Stono freedom fighters are connected to the current discourse. The area commemorating their demonstration of #BlackSelfRespect is named the Stono River Slave Rebellion Site.

I’ve known rivers …

Langston Hughes credited the Mississippi River for inspiring his 1920 gem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.” His grandmother told him that during the plantation era of Black enslavement, all hope was lost for a Black person “sold down the Mississippi.” This river of Black despair touches Michael Brown’s St. Louis, Fannie Lou Hamer’s Mississippi and post-Katrina New Orleans. Yet even in the swamps of misery, #BlackSelfRespect, Black defiance flourished.

Laura McGhee and her family were in the center of the Leflore County [Miss.] freedom movement. Mrs. McGhee was a widow, a small farmer, and one of the first county residents to support the SNCC voter registration campaign in Leflore. McGhee’s land was used for voter registration classes, meetings, rallies, refuge for tenants displaced for supporting the voter registration campaign, as well as collateral to bail out Movement activists. The McGhee family was reputed to “take no sh*t,” while they also “gave sh*t out.” Mrs. McGhee was a clear example of the fact that the Black armed resistance tradition was not exclusively male. She was an active participant in the defense of her household and property (Umoja, 2013, p. 72).

Black art has documented and sustained our Laura McGhees, our Black resistance. Prior to European contamination, Black music and literature reflected a spiritual reverence for the Creator, Earth and Black life. Songs weren’t for solo enjoyment, but a means to fortify communities, remain close with ancestors. Dr. Scales informs us that African griots were documentarians of ancient society who used music and storytelling to preserve and transfer centuries of history. Napoléon, in addition to hordes of European and Arab invaders, grasped the force of Black art and therefore made destroying and looting African monuments a primary objective of cultural imperialism. Jack Shuler’s “Calling Out Liberty” provides a profound illustration of the power and potential of Black music.

“The rebels’ agenda was rebellion. For whites within hearing, the sound of the drums must have been disconcerting. Drums had been a source of unease among Europeans, who, from their earliest contact with Africa, feared the use of drums. In the minds of most Europeans, drums were linked with rebellion or warfare, and because of these violent associations their use was subject to regulation. Laws banning the use of drums by slaves were established in 1688 and again in 1717 in Jamaica, in 1699 in Barbados, and in 1711 and again in 1722 in St. Kitts. A similar law would go into effect in South Carolina in the aftermath of the Stono Rebellion.” (2009, p. 78)

Rebellion is Black rhythm. Fela Kuti. Miriam Makeba. Bob Marley. Tupac Shakur. Mahalia Jackson. Capoeira. Black instrumentation has provided a potent, global soundtrack for Black insurrection. Consequently, drums have not been forbidden, but co-opted. Black artists are seldom furnished with coins, cameras and comfort for making sounds that promote constructive thinking and high moral aptitude. Most often our sonic environment is as polluted with racist toxins as the water we drink, air #WeCantBreathe.

Third-generation physician, author and psychiatrist Dr. Frances Cress Welsing challenged Black people to use February as a time to assess our progress toward and objectives for replacing racism with justice. Black laurels should not satisfy, but remind and rekindle our courage and commitment to the family business of Black liberation. Minister Malcolm, Langston Hughes and the rivers, oceans of Black genius would expect, accept, nothing less.

Gus T. Renegade is the host of The C.O.W.S. Talk Radio – a platform designed to dissect and counter Racism. He has interviewed and researched authors, filmmakers and scholars from around the globe.

References

Fu-Kia, K. Kia Bunseki and A.M. Lukondo-Wamba. “Kindezi: The Kongo Art of Babysitting.” Black Classic Press, 2000

Shuler, Jack. “Calling Out Liberty: the Stono Rebellion and the Struggle for Human Rights.” University Press of Mississippi, 2009

Umoja, Akinyele Omowale. “We Will Shoot Back: Armed Resistance in the Mississippi Freedom Movement.” NYU Press, 2013