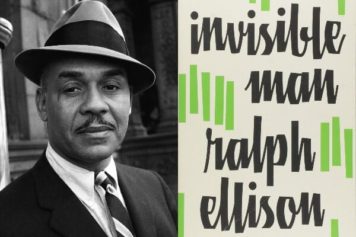

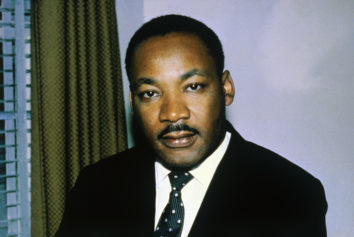

The FBI’s incessant monitoring of Black leaders like Martin Luther King and W.E.B. DuBois is now a well-known parcel of American history. But it turns out J. Edgar Hoover’s obsession with Black culture and the activities of Black thinkers went so deep that the FBI had thousands of pages on dozens of prominent Black writers, including Claude McKay, Ralph Ellison and Lorraine Hansberry, stretching across much of the mid-20th century.

This treasure trove was discovered by scholar William Maxwell, associate professor of English and African-American studies at Washington University in St. Louis, who got his hands on the many newly declassified documents with the use of freedom of information requests. Not only do the files contain thousands of pages of notes detailing the movements of these great writers, but there were essentially book reviews critiquing their work—often written before the manuscripts were even published, meaning the FBI’s reach extended into the publishing houses.

Maxwell has compiled his research into a new book, “FB Eyes: How J Edgar Hoover’s Ghostreaders Framed African American Literature,” which is scheduled to be published on February 18 by Princeton University Press. The book says much of this surveillance was fueled by Director Hoover’s “personal fascination with black culture.” As a result, the FBI became a “most dedicated and influential forgotten critic of African American literature.”

Interestingly, Maxwell said it was clear that the writers were aware of the FBI snooping, based on some of their writings.

There are digital copies of 49 of the FBI files available to the public online. Maxwell said the sheer volume of the files comes out to 13,892 pages—”or the rough equivalent of 46 300-page PhD theses,” Maxwell writes in the book. “FBI ghostreaders genuinely rivaled the productivity of their academic counterparts.”

“From the beginning of his tenure at the FBI … Hoover was exercised by what he saw as an emerging alliance between Black literacy and Black radicalism,” Maxwell said in an interview with The Guardian. “Then there’s the fact that many later African-American writers were allied, at one time or another, with socialist and communist politics in the U.S.”

Maxwell first came upon the enormous stash when he submitted a freedom of information request for the FBI file of Jamaican writer Claude McKay, a major figure in the Harlem Renaissance. Maxwell was working on an edition of McKay’s poems, which at one point were recited by Winston Churchill. What he got back was a file that was 193 pages in length, chasing McKay all across the world. Knowing there likely was a lot more there, Maxwell made 106 freedom of information requests about what he describes as “noteworthy Afro-modernists” to the FBI.

Of the 1o6, a total of 51 had files, ranging in size from three to 1,884 pages.

“I suspected there would be more than a few,” Maxwell said. “I knew Hoover was especially impressed and worried by the busy crossroads of Black protest, leftwing politics, and literary potential. But I was surprised to learn that the FBI had read, monitored, and ‘filed’ nearly half of the nationally prominent African-American authors working from 1919 (Hoover’s first year at the Bureau, and the first year of the Harlem Renaissance) to 1972 (the year of Hoover’s death and the peak of the nationalist Black Arts movement). In this, I realized, the FBI had outdone most every other major institution of U.S. literary study, only fitfully concerned with Black writing.”

The result is the first extensive expose ever published of the FBI’s more than 50 year monitoring of Black writing. Maxwell writes that the FBI scrutinized passport records and “for scraps of criminal behavior and ‘derogatory information,’” with some writers even threatened by “‘stops’, instructions to advise and defer to the Bureau if a suspect tried to pass through a designated point of entry” to the U.S.

With the help of informers, the FBI was able to review works such as Lorraine Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun” and Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man” before publication. On the website where the public can access files, of Hansberry the site says, “FBI officials monitored the progress of Raisin even before it premiered on Broadway, and sent an especially literate undercover agent to a Philadelphia try-out at the Walnut Theatre. ‘The play contains no comments of any nature about Communism as such,’ this ghostreader certified in a sensitive review, ‘but deals essentially with negro [sic] aspirations, the problems inherent in their efforts to advance themselves, and varied attempts at arriving at solutions.'”

“What did the FBI learn from these dossiers? Several things,” Maxwell told The Guardian. “Where African American writers were traveling, especially during their expatriate adventures in Europe, Africa, and Latin America. What they were publishing, even while it was still in press.”

The bureau also considered “whether certain African Americans should be allowed government jobs and White House visits, in the cases of the most fortunate” and “what the leading minds of black America were thinking, and would be thinking.”

Maxwell said the files also show that “some FBI spy-critics couldn’t help from learning that they liked reading the stuff, for simple aesthetic reasons.”