A defining moment in the life of Dr. Matshidiso Moeti, the World Health Organization’s new regional director for Africa, came when she was 9 and her father realized that her little sister’s mathematics textbook was below even the level he had studied as a poor child on a South African farm.

He and his wife had both graduated from one of the country’s top medical schools, the University of the Witwatersrand, but the National Party that came to power in 1948 had imposed “Bantu education” on Blacks, preparing them only for subservient jobs under apartheid.

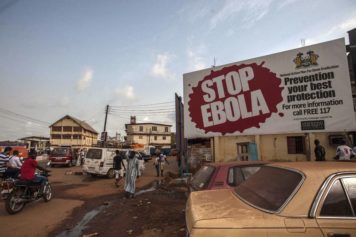

“My father decided right then that we would move to Botswana so his children could get a better education,” Dr. Moeti, 60, said in a telephone interview on Monday from Geneva, where on Tuesday she was appointed to the new W.H.O. post that will put her at the forefront of an international effort to stop the spread of Ebola.

Her parents’ determination, coupled with her own — she earned her medical degree at the University of London’s Royal Free Hospital, ran tuberculosis and H.I.V. programs in Botswana and has worked for three United Nations agencies — made her a much-praised choice for a job that is, for once, a focus of world attention.

The W.H.O.’s Africa office has long been criticized as a cozy sinecure for officials with political connections but little drive, and its slow reaction and initial resistance to direction from the Geneva headquarters in the early months of the Ebola outbreak have been held partly to blame for the epidemic’s getting out of control.

“There is no question that, as a region, we need to up our game,” Dr. Moeti said. “The W.H.O. is reforming, and one of my intentions is to fast-track reform in the region, too.”

Competence tests for the staff and audits of job performance by outside consultants will be among the changes, she said. The W.H.O.’s big donors, including the United States, have been demanding that the agency be more efficient and effective.

During the selection process, Dr. Moeti said, she was not pressured to promise jobs to anyone in return for any country’s vote, which is known to have happened in the past.

“Things have moved on from that,” she said.

Several prominent public health leaders expressed confidence in her.

Read More at NY Times