Excessive use of police force has been stealing the lives of unarmed Black people all across the nation and encouraged thousands, perhaps even millions, of people to come together in an attempt to remind the world that #BlackLivesMatter.

It’s a phrase that refers to both the physical and systemic threats that are being posed against the well-being of Black citizens, but the psychological damage that these racist systems are creating have also been contributing to the deaths of many Black men.

Suicide has become the third-leading cause of death for Black men between the ages of 15 and 24, a 2010 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report revealed.

Even more troubling is what experts say makes Black men so prone to developing depression and eventually committing suicide.

Constantly being faced with racism and discrimination is causing even more Black men to become depressed, which often goes untreated in the Black community and can end in tragedy.

“Black boys are more depressed because they believe their physical safety is always being threatened,” said Dr. Waldo E. Johnson Jr., the author of “Social Work with African American Males: Health, Mental Health and Social Policy,” during a symposium at the University of Chicago. “Their families are economically poorer than whites and many Black families live below the poverty line.”

Those socioeconomic challenges combined with the lack of appreciation being expressed for Black lives is driving depression rates and taking a serious stab at the psyche of Black men.

“If you make someone feel like you don’t even care if they are alive or not after police altercations, how do you think they are going to react after years and years and years of telling someone that they don’t matter,” said Sameen Mannan, a sociology major at Georgia State University. “It’s so sad to say it like this but it’s almost like, ‘Well, if you don’t care about my life why should I?’ ”

A report by Dr. Earlise Ward of the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Nursing, suggests that Mannan’s sentiments are absolutely correct.

“Many African-American men are burdened by depression due to unique stressors including racism and discrimination, educational attainment, occupational status, income and poverty,” the report said.

With racial tensions growing in America and the recent spate of highly publicized unarmed Black men being killed by officers, Black men are even more susceptible to depression and could ultimately become another suicide statistic.

With that being said, it’s important that the Black community squelches the stigma surrounding mental illness and creates an environment where Black men can comfortably express their feelings without being portrayed as weak.

“I think we’re always reminded that it’s not OK to cry,” said Darius Herring, a 22-year-old New York native who has battled with depression and even made suicide attempts in the past. “I had a single mom so I definitely couldn’t cry. I got a house full of women now so I can’t be crying with them.”

Herring laughed after making the comment, but it was clear that the idea of not being allowed to show emotion still struck a sensitive place for him.

He explained that as “the new man of the house” he couldn’t “show any signs of weakness.”

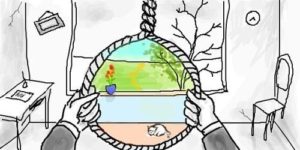

“It just wasn’t allowed, so when I went through these really emotional, unstable periods I had to just hold it in and it just got worse,” he said. “After a while, I just couldn’t imagine — have you seen that picture where it’s like a rope and the middle of the rope is like color but everything else is black and white?”

It’s an image that circulated on social media shortly after comedian and actor Robin Williams committed suicide.

It was an artist’s depiction of what it’s like to deal with depression, but Herring says it’s more than just art; it’s absolutely accurate.

“You really think death is a better option than life,” he said as he recalled his battle with depression. “And you think about death in a really weird, peaceful way. Almost dreamy.”

Herring said that there was no particular moment that launched his battle with depression.

Instead, he said it was just an overall “lifestyle of feeling like [he] didn’t matter.”

As thoughts of suicide filled his mind, he never found anyone to open up to, and it wasn’t until a failed suicide attempt that he was forced to seek medical attention.

Herring was immediately diagnosed with depression, but some reports indicate that even getting the diagnosis was a luxury that many Black men don’t get.

Reports show that most Black men are assumed to be schizophrenic while their white counterparts are more commonly diagnosed with depression.

A 1990 report stated that “schizophrenia diagnosis rates among African Americans were sometimes twice as high as those for Whites, but that Whites were diagnosed with affective disorders (i.e. depression) at nearly twice the rate of African Americans.”

“A lot of times it’s issues around gender performance, expectations, how we look,” said Dr. David Malebranche, an internist and primary care physician at the University of Pennsylvania, to News One. “With Black men, people don’t want to see us as depressed and it’s not on the radar for health care providers to see us as depressed.”

Without the proper diagnosis, young Black men are not able to get the proper medical attention and they remain at risk of attempting suicide.

It can be incredibly difficult for Black men to get the help they need when they are faced with emotional turmoil.

The first step toward reducing suicide rates for Black men is to first ensure they have the proper support if they are faced with the darkness.

As the nation continues to remind authorities that “Black lives matter,” the reality is that we must also adamantly remind our own young Black men that their lives do, indeed, matter.