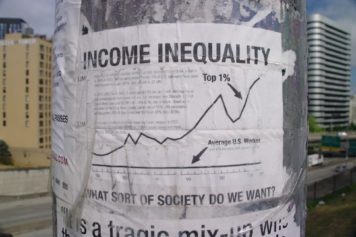

Higher levels of income inequality are directly related to an increase in Black deaths—while the exact opposite is true for white people, a new study revealed in findings that even the researchers were at a loss to explain.

The researchers behind the University of California at Berkeley study admitted that even they were shocked at their findings.

It is no secret that higher income inequality leads to more deaths at the low end of the income scale, but the latest study by associate professor Amani Nuru-Jeter found that the trend doesn’t seem to apply to white people.

Based on Census data from more than 100 metropolitan areas with at least a 10 percent African-American population, every unit increase in income inequality led to anywhere from 27 to 34 more deaths among Black people.

Oddly enough, however, this trend was reversed for white people.

Every unit increase in income inequality among white people actually resulted in up to 480 fewer deaths.

“Other studies have found poorer health outcomes when income inequality increases, so the results for Blacks were not surprising,” Nuru-Jeter said, according to UC Berkeley website. “What I didn’t expect to see were the results for whites, and our study doesn’t explain this inverse relationship between income inequality and death for this group.”

Nuru-Jeter went on to say that the unusual results certainly call for “further exploration.”

While the study couldn’t confirm what caused the trend, Nuru-Jeter had a reasonable guess.

“We do know that the proportion of high-income people compared to low-income people is higher for whites than for African Americans,” Nuru-Jeter explained. “It’s possible that the protective effects we are seeing represent the net effect of income inequality for high-income whites.”

As for the correlation between mortality rates and income inequality for African Americans, researchers believe racial segregation was a key factor.

“What we’re finding is that at the population level, income inequality may be a proxy for racial segregation, particularly for Black people,” Nuru-Jeter continued. “Racial segregation and concentrated poverty can’t be completely disentangled from income inequality. In our study, racial segregation completely explained the effect of income inequality on mortality among Blacks…addressing the negative impact of racial segregation will be important for improving overall population health.”

Researchers also suspect that knowledge of racism and discrimination has a serious impact on the health of African-Americans and believe that also contributed to the higher mortality rates for Blacks.

“Place matters. That’s not news,” Nuru-Jeter added. “What is news, however, is that place matters differently for different groups of people. The idea is that the sense of being left behind, of not making it, of living in an area where there is more crime, more pollution, fewer jobs, lower-quality schools, less access to parks and green space, all comes with stressors that impact health.”

The study revealed that there is still much more research to be done on the issue but it also served as yet another confirmation that immediate action is needed in Black communities across the nation.

“Although more research is needed, we can still act on what we know about racially segregated areas,” she continued. “These are structural issues that require investment from policy leaders so that everyone, regardless of zip code, has equal opportunities for health and well-being.”