While Beyond the Lights is exactly what you would expect from a romantic drama about a young star on a desperate journey to discover herself in the midst of the blinding lights that come with fame and fortune, the film does bring a different perspective to the classic tale by providing insight into some of the serious issues that plague many young men and women in the Black community.

There is no way to escape the fact that the plot is a bit clichéd and, within the first 20 minutes of the film, the average moviegoer will already know exactly what’s going to happen throughout the rest of the film.

Despite the lack of surprises in the plot, the film still manages to pull at your heart strings, teach a few valuable lessons and make you think a little harder about the culture in which we are raising our young men and women.

With the help of two outstanding leads, who are both respected veteran actors, a flawless soundtrack and some impressive visual elements, Beyond the Lights will have you whole-heartedly rooting for each of the characters as they navigate their own complicated personal lives.

The film introduces viewers to a younger version of the soon-to-be scantily clad, purple-haired songstress Noni, played by the lovely Gugu Mbatha-Raw.

At a younger age she is a curly-haired girl with thick glasses who has been blessed with the soulful voice that she puts on display at a local talent show.

After belting out Nina Simone’s “Blackbird,” which is essentially the theme song for how Noni really feels about her life in general, she is named a runner-up and snatched off the stage by her mother.

Minnie Driver takes on the role of the overbearing mother-turned-manager, Macy Jean, who seems to be thoroughly convinced that money and fame can indeed buy happiness, even if it’s at the cost of her own daughter’s joy and self-respect.

As the classic tale goes, however, the movie works tirelessly to peel back those cold layers and expose the good intentions behind what at first seemed to be a completely selfish mother.

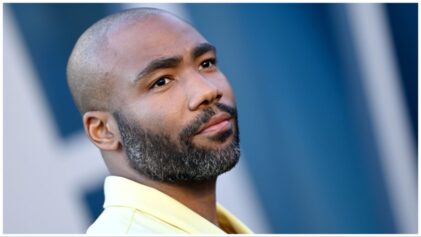

Before moviegoers are introduced to the tiny speckle of goodness in Macy Jean’s heart, however, they are first introduced to officer Kaz, played by Nate Parker, who has been assigned the task of essentially babysitting the star for the night—a la Kevin Costner and Whitney Houston in The Bodyguard—and ends up saving her from the ultimate tragedy.

One thing leads to another and a romance is formed between Kaz and Noni– one that may be too heavily reliant on the concept of an unspoken conversation that happens between two complete strangers when they lock eyes.

All the while Kaz is dealing with his own overbearing parent—a single father, played by Danny Glover, who is pushing his son up the political ladder in hopes to see him become president some day.

The movie presses forward to show the rise and fall and rise again of Noni and Kaz’s relationship and the singer slowly starts to strip away physical elements of her image in order to uncover the natural beauty that was underneath the entire time.

The film, written and directed by Gina Prince-Bythewood—who also brought us the now classic Love & Basketball—delivers on its fair share of laughable moments, great eye candy for moviegoers of both sexes and the type of drama that actually gets you to jump in your seat a few times.

Where the movie really shined, however, was the way it presented social commentary on the hypersexualization of Black women in the music industry.

The young girl who was once singing “Blackbird” at a talent show is seen throughout the movie in outfits that barely classify as clothes and being featured in a music video where her rapper boyfriend, played by real rapper Machine Gun Kelly, is groping her under a dinner table while dropping some rather explicit bars.

It pushes the idea that women are sexual objects to the limit when Machine Gun Kelly’s character, known as Kid Culprit in the film, forces the star down to her knees during a live performance and introduces a major breaking point for Noni who is tired of “hiking up” her skirt for the cameras.

Then there is the presence of a single mother and a single father—both of whom honestly do want the best for their children.

While both parents seem cold and careless in the beginning of the film, as the drama unfolds they both stand to be representations of parents who want to do right by their child as the rest of the world is waiting for them to fail, particularly Noni’s mother who was just a teen when she had her.

Finally, Noni’s transformation into the soulful crooner she always dreamed of being reveals a beautiful woman who has finally embraced her natural hair, minimal makeup and dresses like a respectable adult rather than a star who is merely flashing her body for publicity.The physical transformation is only a metaphor for a greater change happening in Noni.

The girl who was created out of a greed and fear and pushed to be the “sexy” woman that every man wanted and every lady envied, had finally bid farewell by the end of the film.

What stood in her place was the type of image that many young women in the Black community should admire as it encourages a comfort with who you are rather than what money can make you.

It seems as if mainstream media is finally realizing that the culture surrounding a Black woman’s hair deserves to be at the center of discussions about racial identity, representations of class and perceptions of one’s self.

From Kerry Washington’s character Olivia Pope in “Scandal” to Viola Davis stripping off her wig and false eyes lashes in “How To Get Away With Murder,” we are starting to see a focus on what artificial hair pieces and other superficial “beauty aids” mean to Back women. The hair serves as a representation of whether or not the woman is vulnerable, honest and open (often shown through natural hair) or guarded and cold (often shown through hair extensions).

All in all, “Beyond the Lights” is an enjoyable journey that is cinematically presented in a way that can teach young Black men and women about the value in taking control of their futures and truly embracing who they are.