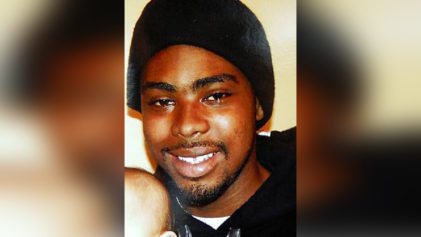

The 22-year-old Grant III was killed by a single shot to the back from BART Officer Johannes Mehserle early in the morning on New Year’s Day 2009 in Oakland. The incident was captured on cellphone video by other passengers, prompting protests and riots and outraging much of the nation.

In January 2010, BART came to a $1.5 million settlement with the mother of Grant III’s young daughter, Tatiana, and a $1.3 million settlement with his mother, Wanda Johnson. BART also awarded $175,000 to each Grant III’s five friends who were with Grant when he was shot.

Mehserle was convicted of involuntary manslaughter in a 2010 criminal trial, and was released from a Los Angeles County jail in June 2011 after receiving credit for time served.

When he testified in Oscar Grant Jr.’s civil trial on June 11, 2014, Mehserle, 33, cried in open court as he described shooting Grant III as he lay face down on the train platform. Mehserle claims he mistakenly used his service revolver when he wanted to grab a Taser.

“The man was killed in cold blood: No ifs, ands or buts about it,” Grant Jr., said during his testimony, according to the Oakland Tribune. “I don’t care how they say it, it was not an accident.

“They took the most precious thing in the world to me—my only child,” said Grant Jr., 50.

The jury was aware that Grant Jr. is serving time in Solano state prison, but was not told any details of his criminal record—nor the details of Grant III’s own arrests and convictions before his death.

As described by the Tribune story, the spectators in the courtroom could hear Grant Jr.’s leg shackles as he walked to and from the witness stand dressed in a gray suit, blue shirt, and multicolored tie. The father showed the jury a photo of himself dressed in prison blues and holding baby Oscar at the Old Folsom Prison as he talked about a long and close relationship with his son facilitated through prison visits, letters and phone calls.

Grant Jr. told the jury he filed the lawsuit out of a respect for his son. He said he wants to help take care of his granddaughter Tatiana and he wants the chance to pay restitution for his own crimes.

“I’ve already paid for my crime, I’d like to give back to the community,” said Grant Jr., who according to a trial brief filed by his lawyer expects to be paroled in the next couple years after four prior denials by the state parole board.

But when Mehserle’s attorney Mike Rains, who also defended Mehserle in the 2010 criminal trial, questioned Grant Jr. about the depth of his relationship with his son, the father grew combative, according to the Tribune. Rains asked if he knew the names of the schools Grant III attended, whether he played high school sports, knew his daughter’s birthday, his friend’s names, or whether he had a job or a cell phone.

Grant Jr. could not answer many of the questions.

Rains was also quick to point out some of the answers that differed from those Grant Jr. gave during a 2010 deposition.

Rains asked him if he was so eager to get out of prison to be with his son, why did he keep getting in trouble in prison over the years for offenses such as drug possession?

“What does my prison record have to do with your officer killing my son, shooting my son in the back?” Grant Jr. responded angrily.

Grant Jr. said Grant III last visited him in prison in 2002, and he last spoke to his son three days before his Jan. 1, 2009 death.

“I told him, ‘If you decide you wanna drink, don’t drive your car. Catch the bus or ride the BART,'” Grant Jr. said.

The jury deliberated a day before choosing to deny Grant Jr.’s claim that Mehserle’s intentional shooting of his son deprived him of a previous existing relationship that involved deep attachments and commitments to one another, and the sharing of special community of thoughts, experiences and beliefs.

“Five years later, the wounds are still there – I’m relieved that we can finally put this tragedy behind us, not just for Johannes and his family, but for the entire community,” Mehserle’s attorney Rains said in a statement.