The question of what does it mean to be African is multifaceted and has many complexities that are found in the interdependence of past experiences and present realities. Yet all are essential to understanding the path toward the future.

Accordingly, it is vital to approach the proposed question with a clear and unrestricted understanding. To be more exact, in order to adequately deal with this question and place it in its proper context, we must distinguish between and interrogate narrowly constructed racialized conceptualizations from textured cultural formations.

With this, it must be noted that the concept or descriptor “Africa” was a construct placed upon the geographical land mass where a variety of people with connected histories and shared cultural elements lived for millennia. Where people created and molded ways of understanding the world through the development of human capacities captured in math, science, language evolution, religion/spirituality, understanding the link between nature, humanity and the universe, holistic health practices, etc. that guide our most intimate lived realities even today.

While the true origins of the concept or descriptor Africa are debated, what we do know for sure is that there are at least seven points of origin. What is not debated is that all of them were derived from foreign intellectual projects and practical experiences.

Being so — we can add with certainty, as history teaches that — the descriptor was used widely during the Roman imperial era, initially to refer only to North Africa — originally called Libya by the Greeks. This is centuries before it was extended to encapsulate the whole continent, specifically from the end of the first century.

From this, it is reasonably understood that, conceptually, Africa was an imperial construct whose application was both gradual and contradictory. As the name embraced the rest of the continent, it was divorced from its original North African referential point to become increasingly confined to the regions referred to in Eurocentric and sometimes Afrocentric conceptual mapping as “sub-Saharan Africa” — often seen as the location of the “real” Africa.

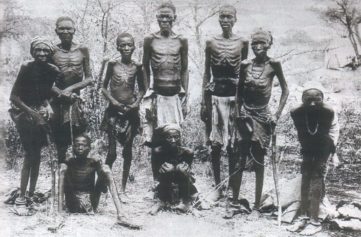

The divorce of North Africa can certainly be understood within the history of Arab invasions in the seventh century. However, its epistemic and ideological propensity became apparent with the emergence of Eurocentricism following the rise of “modern” Europe — the European nation-state. For Africa, this entailed, initially and destructively, the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, out of which came the forced displacement of millions of people from their ancestral lands and the formation of African Diasporas that appropriated and popularized the name Africa. This proved to be the lens through which Africa became increasingly racialized, a process which attempted to strip the various people of the cultural elements that linked them to each other, to nature and the universe. (Note: I say attempted because despite the best efforts of those who argue otherwise, the deep-rooted cultural elements were never really completely stripped from them. Moreover, it must not be lost that, despite what the dominant narrative attempts to assert, not one slave was taken from the continent, but various people were enslaved.)

Nevertheless, out of these processes, it is far less clear the exact point when the appropriation of Africa, as a self-defining identity, became the “accepted” descriptor in the various Diasporic regions and among the numerous societies that make up the continental land mass we refer to as Africa.

The (re)connecting of Africa with sub-Saharan Africa, Africa South of the Sahara or Black Africa that we find common in our interaction with and about Africa ultimately offers us a racialized view of Africa — Africa as a biological construct, as the “black” continent. All of this was born in the processes of Europe attempting to assert its new self in an old world. (Note: It cannot be forgotten that the processes captured in Europe’s assertion into the world were ultimately young in the grand narrative of world history.)

In the end, the reclamation of humanity — the idea implicit within the question of what does it mean to be African — of the people who live on the continental land mass we now accept as or call Africa, the place where the Akan, Hausa, Yoruba, Zulu, Ashanti, etc. live, demands that we clarify and reorient — in this living moment — how we approach this question. What is African? or What it means to be African? must be reoriented to interrogate and properly contextualize Where Africa is from — Its origins? From this, the question of what does it mean to be African must evolve to capture Where Africa is going? It is from here we can begin to understanding the processes of reclaiming one’s humanity, the first step in actualizing self-determination.

James Pope, Ph.D., maps the traditions and continuities of Africana thought and behavior as it relates to human rights, social movements, resistance to race as a cultural-ideological class construct, and critical consciousness formation. Currently, he is completing a book manuscript that explores the impact of race on the critical human rights consciousness of African-Americans.