“For the complexion of men, they consider Black the most beautiful. In all the kingdoms of the southern region, it is the same.”

–Nan Ts’i Chou

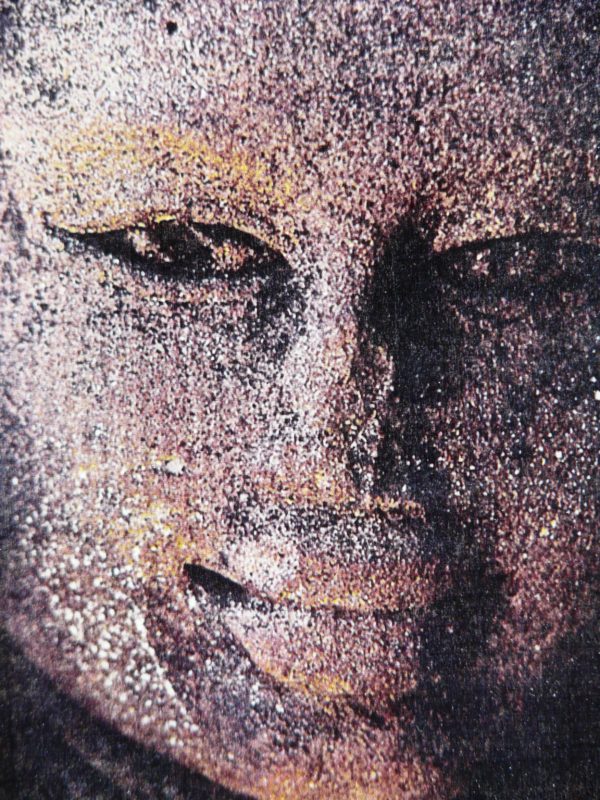

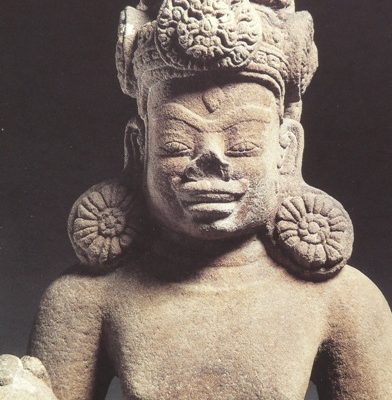

The great classical civilizations of Southeast Asia are Angkor in Cambodia and Champa in Vietnam. Much of our knowledge of early Southeast Asia is derived from Chinese and Indian sources. The builders of Angkor were the Khmers. The Khmer men were described by the Chinese as “small and Black.” In modern times, as early as 1923, Harvard University anthropologist Roland Burrage Dixon noted that the ancient Khmers were physically “marked by distinctly short stature, dark skin, curly or even frizzly hair, broad noses and thick Negroid lips.”

THE KINGDOM OF ANGKOR

Early in the ninth century, King Jayavarman II (802-850) unified the Khmer kingdom and identified himself with the powerful Hindu deity Shiva. The Khmers of Angkor were sophisticated agriculturalists, advanced engineers, aggressive merchants and intrepid warriors. They developed a splendid irrigation system (with some canals extending forty miles in length), and created grandiose hydraulic works. The hydraulic system of Angkor was used for transportation and for rice cultivation to support a surrounding population estimated at one million people.

During the reign of King Indravarman I (877-889), for example, the vast artificial lake known as the Indratataka was completed. For the harsh purposes of war the Khmer engineers designed machines to launch fearsome arrows and hurl sharp spears at their enemies, and rode boldly into battle atop ornately outfitted elephants.

In the Khmer language, Angkor means the city or the capital. In 889 King Yasovarman I (889-900) constructed his capital on the current site of Angkor, and over the centuries Khmer monarchs augmented the city with their own distinct contributions.

Angkor eventually covered an expanse of 77 square miles and was designed to be completely self-sufficient. The Khmers were magnificent builders in stone and for more than 600 years successive Angkor dynasties commissioned the construction of meticulously detailed temples, such as Banteay Samre, marvelous artificial lakes like the Indratataka, and incomparable temple-mountains, including Angkor Wat–the crown jewel of Angkor and estimated to contain as much stone as the fourth dynasty pyramid of King Khafre in Old Kingdom Kmt (ancient Egypt).

ANGKOR WAT

Called “the largest stone monument in the world,” Angkor Wat, the most famous of the Khmer stone structures, took 37 years to build. During this period, millions of tons of sandstone used in its construction were transported to the site by river raft from a quarry at Mount Kulen, located 25 miles to the northeast. Angkor Wat rises in three successive flights to five central towers that represent the peaks of Mount Meru–the cosmic or world mountain that lies at the center of the universe in Hindu mythology and considered the celestial residence of the Hindu pantheon. The towers of Angkor Wat (the tallest of which rises about two hundred feet above the surrounding flatlands) are Cambodia’s national symbol. The temple’s outer walls represent the mountains at the edge of the world, while the moat surrounding the temple represents the oceans beyond.

Angkor Wat dates from the 12th century reign of Suryavarman II (1113-1150) when the Khmer dominion over Southeast Asia was at its zenith, with an empire stretching from the South China Sea to modern Thailand, as far north as the uplands of Laos and as far south as the Malay Peninsula.

THE KINGDOM OF CHAMPA

The Cham are believed to have settled along the coastal plains of central Vietnam (Annam) more than two millennia ago. The economy of Champa was based on agriculture and maritime trade. They exported rice and forest products, including sandalwood, and essentially dominated the area from about the fourth century through the 13th century.

Chinese dynastic records from as early as 192 C.E. reference a kingdom of Lin-yi, which meant the “land of Black men.” The kingdom of Lin-yi was known as Champa in Sanskrit documents. They stated the inhabitants possessed “‘black skin, eyes deep in the orbit, nose turned up, hair frizzy” at a period when they were not yet subject to foreign domination and preserved the purity of this type. These records expressly state that: “For the complexion of men, they consider Black the most beautiful. In all the kingdoms of the southern region, it is the same.”

During this same period Cham ships, known to the Chinese by the appellation kun-lun bo (the “vessels of Black men”), were navigating the currents of the Indian Ocean from Southeast Asia to Madagascar.

Among the major centers of Champa were those based near Dong Duong, Tra Kieu and Pandulanga (Phan-Rang). The great southem capital was Vijaya (Binh Dinh), and the early northern capital and religious center was Mi Son.

More than 70 temples were constructed at Mi Son from the seventh century through the 12th centuries. The masterpiece of Cham architecture at Mi Son was an enormous, 70-foot-high stone tower that was destroyed by United States Army commandos in August 1969.

PRESSURES FROM THE NORTH

By the beginning of the 10th century the Cham were being aggressively pressured and gradually absorbed by Sinicized Vietnamese. By the end of the century, Sinicized Vietnamese had annexed the northern provinces of Champa. In 1225, the Vietnamese once again followed a course of aggression, and in 1283 the Mongols under Kublai Khan desolated the entire coast. All told, however, more than a hundred temples and a multitude of exquisite statuary have survived to remind us of the former splendor of the traders, artisans and royalty of the realm of the Cham.

KING JAYAVARMAN VII: ANGKOR’S MOST PROLIFIC BUILDER

The reign of Jayavarman VII (1181-1220) marks the height and the beginning of the decline of the kingdom of Angkor. Jayavarman VII (the prefix of whose name, Jaya, in Sanskrit, means “victory”) was so successful in his military campaigns with Champa that during the last 17 years of his reign Champa was virtually a Khmer province. Jayavarman VII lived more than nine decades, ruling with strength and wisdom.

In 1181 Jayavarman VII was proclaimed king in the battled-scarred and essentially devastated Khmer capital, and many of the monuments of Angkor reflect his Herculean reconstruction efforts and seemingly ceaseless building projects. Jayavarman VII built more than any other Khmer king. It is calculated that he built more than all the others put together. In fact, as magnificent as it is, Angkor Wat is only one of 215 sites in the immediate region. Other famous sites include the Bayon, the sculptured stone mountain at the center of the six-square-mile walled city of Angkor Thom, about a mile northeast of Angkor Wat, and the capital of the Khmer empire from the late 10th century through the early thirteenth century.

THE DECLINE AND FALL OF ANGKOR AND CHAMPA

After the death of Jayavarman VII, Angkor began to decline, and no great monuments were constructed after his reign. And thus were eclipsed the bright shining lights of the Black presence in Southeast Asian civilizations—the kingdom of Angkor and the kingdom of Champa. And yet the monuments and the faces etched in stone survive to us the story.

*Runoko Rashidi is a noted historian, a world traveler and the author or editor of several books. Among his most recent works are Black Star: The African Presence in Early Europe, in 2012, and African Star over Asia: The Black Presence in the East, in 2013. Rashidi is currently coordinating African heritage tours to many parts of the world. For more information please write to [email protected] or go to his web site at www.travelwithrunoko.com