For a show about a group of stuffy, aristocratic Brits, Masterpiece Classic’s Downtown Abbey has become an unconventional pop culture sensation over the past few years. Downton is half drama, half history lesson, profiling a British family’s evolution in the 1910s and 1920s—becoming one of the most popular period pieces in recent memory.

Viewers have watched the aristocratic Crawleys and their servants, who cohabitate the ancient manor of Downton Abbey, face struggles both worldly and intimate, from World War I to the death of the family’s youngest daughter.

Creator Julian Fellowes has managed to conjure historically meaningfully storylines that also elicit timeless themes. A few of which include daughter Sybil’s fight for women’s rights, but at times contradictory desire to remain close to her conservative family, and patriarch Robert’s inability to adapt to the changing world around him following World War I.

As his mother, the Dowager Countess (played deliciously by Dame Maggie Smith) quipped, “when you give these little people power it goes to their heads like strong drink,” referencing the breakdown of class divisions, yet conceded “war breaks down barriers.”

However, despite this focus on a modernizing world, Downton Abbey has also come under criticism for not featuring a diverse cast. All of its series regulars are currently white. Fellowes recently spoke out on these criticisms, claiming “You have to work it in in a way that is historically believable.”

Fellowes is correct in terms of the larger picture. A rural estate, like Downtown Abbey, would have primarily been staffed by Anglo-Saxons even around 1910, owing to complex set of historical circumstances, including rigid class boundaries, the legacy of a feudal economy, and population demography. Critics have also commented that you never see any African or Indian extras even in the shots of the town that borders the estate.

This is perhaps a bit extreme, although rural English towns were certainly not diverse places around World War 1. Historians estimate most Africans resided in urban areas such as London and port cities such as Liverpool and Bristol, yet still only accounted for 1.5% of the population by the time of Downton’s setting.

Thus, while Fellowes is certainty not looking to upset the common narrative of a whitewashed Britain—a harder, but arguably more worthwhile endeavor — he also doesn’t stray too far demographic reality.

Possibly due to these criticisms, in Season 4 Fellowes does plan to add a black actor, who will play a singer from London. He also commented on wanting to add an Indian character, as there was a sizable Indian population in Britain at the time.

The real problem, however, is not the diversity within programs like Downton Abbey, but across them.

Downtown is an export. It’s produced by a British company and largely features only British actors. A characteristic Downtown Abbey shares with other popular period pieces from the last decade. Showtime’s The Tudors (2007-2010) which profiled the wives and political upheaval during the reign of Henry VII, was also produced by a British company and profiled a piece of British history.

For whatever reason, American production companies don’t seem to be as interested in producing quality period pieces. From the lack of period pieces currently on primetime or premium channels, it seems our only appetite for history lies primarily outside of our own. American television period pieces are few and far between, but have yet to conjure the magic of historical pieces produced by the Brits.

HBO’s Boardwalk Empire and ABC’s Mad Men, America’s two must successful stabs at the period piece in the last decade, take a perhaps even more white-washed approach, one about Jersey mobsters, the other Manhattan ad execs—arguably worlds even more insular than Downton Abbey.

Critics, rather than complaining about the casts of these shows lacking diversity, might instead call for programing with settings and storylines that better reflect the diversity of America itself, or at least a pivotal historical moment that is meaningful to a wide variety of ethnic groups.

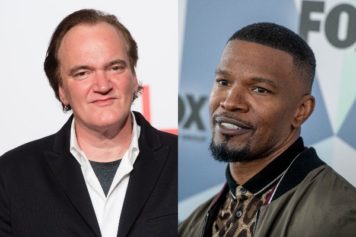

Recent films like Django Unchained certainly indicate public interest in periods such as the Civil War era, which would be a setting rife with discussions of race and history. Django is particularly distinctive as a period piece for highlighting a story that counters the standard historical narrative. Rather than tell a tired tale of the plantation, Django follows the story of a slave who becomes a bounty hunter and journeys across the Antebellum South and Old West to rescue his wife from an abusive plantation owner.

The chief task is for American television producers to make period pieces that fit this model—an enticing narrative set in an equally compelling setting that reflects the diversity of American history. Downtown Abbey, if anything, has proven America’s appetite for quality, non-Kardashian programming. Now, if American producers can only develop a compelling period piece, they will actually achieve a far greater goal of getting Americans to reinvest in their own history, all of it.