As part of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 comes up for challenge this year before the Supreme Court, a group of black conservatives is fervently hoping that the court strips away the protection the federal government has given African-Americans in certain regions of the country that have a discriminatory past.

The act, signed by President Lyndon Johnson in the presence of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks, is considered a key element in the elimination of Jim Crow segregation in the South.

But members of a group called Project 21 filed a brief with the Supreme Court seeking an end to a part of the act. Section 5 requires certain areas with a history of racial discrimination to get federal approval before changing voting processes. Project 21’s brief is in support of Shelby County, Ala., which is trying to stop the federal approvals.

Cherylyn Harley LeBon, former senior counsel for the Senate Judiciary Committee and a co-founder of Project 21, told the Guardian that her group wants Section 5 tossed out because she believes America has changed substantially since the law was signed.

“Now we are in 2013, and the Voting Rights Act was something that came from a historical context. We need to update the law and this part of it is no longer needed,” Harley LeBon said.

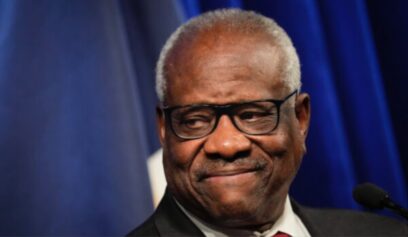

Liberal Supreme Court watchers are worried that the court intends to declare Section 5 unconstitutional. They point to the fact that the court issued a ruling on Section 5 in 2009, refusing to declare it unconstitutional by an 8-1 vote (with Clarence Thomas the only dissenter). Because the court is taking up another Section 5 case so soon, many say the court is on the verge of striking it down.

Harley LeBon said her own father left the Deep South because of racism, but believes circumstances have changed. “Just because issues may be difficult to deal with does not mean they should not be dealt with,” she said.

Civil rights groups such as the NAACP vehemently disagree, saying that recent efforts to change voting laws by many state legislatures demonstrate that Section 5 is still needed.

The act “is single-handedly responsible for much of the progress this country has achieved in terms of electoral equality,” said Myrna Perez, a senior counsel at New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice. “Changing it would have a tremendous impact. There would be no backstop against states or localities that wanted to conduct discriminatory practices in voting.”

Section 5 was used last year to stop Texas from instituting a controversial redistricting plan that opponents said would create extra Congressional seats in predominantly white districts, even though the growth in Texas’ voter rolls was among minorities, particularly Hispanics.

The scheme was called an “extreme example of racial gerrymandering,” aimed at reducing the influence of nonwhite voters, according to the League of Women Voters. The federal courts blocked the plan in August.

“That happened just a few months ago last year,” Perez said.

But Harley LeBon countered that Section 5 was an example of the federal government unfairly intruding into the rights of localities to organize their own procedures. She said the role of Project 21 was to spark discussion about such matters.

“This is what America is all about: having a discussion. There is a whole network of black conservatives. The Democrats do not have a lock on black support,” she said.