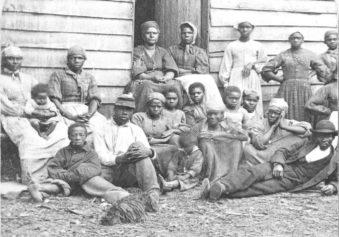

On Freedom’s Eve, the night before the Emancipation Proclamation took effect on Jan. 1, 1863, worshipers gathered in black churches to pray, give thanks and wait for the stroke of midnight, the stirring moment when slaves would officially, and finally, be “forever free.”

Now, on the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s proclamation, the tradition of what became known as Watch Night continues. In Houston, a megachurch observed the night with music, dance and prayer. In Washington, the National Archives put the original document on display. And in Los Angeles, the First African Methodist Episcopal Church marked the day as well, as it has since its founding 140 years ago.

“It’s a tradition with my mother and father. We’d always go back to church to see the New Year come in. We’re always on our knees when the clock strikes 12,” said Enoila Woodard, 71.

Woodard had traveled from Fresno, Texas, to Houston for a Watch Night service at Windsor Village United Methodist Church. She brought along four great-grandchildren, ages 11, 10, 9 and 7.

Bertha Greene, 62, of nearby Missouri City, Texas, grew up attending Watch Night services in Mississippi. “We always did it — we always brought in the New Year at church,” said Greene, joined by her daughter and 11-year-old grandson. “We need to be thankful for what we have, for the year. I really came to show the children what it’s about.”

But perceptions of Watch Night have changed through the years.

“There are a lot of meanings behind it,” said Phillip McKnight, 54, facilities director at Windsor Village. “Some say it started with the Emancipation Proclamation, but it goes back further than that. It’s a thanking for another year — I want to thank God for another year.”

Ray Bady, 42, director of the youth ministry at the 16,000-member church headed by Pastor Kirbyjon Caldwell, agreed that Watch Night had changed over time and that some people may have lost sight of its origins.

“People have made it throughout the years what they want it to be. I think the history needs to be retold, so you know the meaning behind what you’re doing,” he said.

Read more: Molly Hennesy-Fiske, LA Times