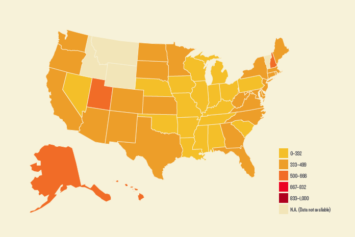

Nearly 6.5 million U.S. teens and young adults—disproportionately black and Hispanic—are neither working nor in school, the very things they need to guarantee they would have the experience needed for the higher-skilled jobs in the marketplace, according to a new report released last week from the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Sixteen percent of black and Hispanic teens 16-19 years old are out of work compared to the national average of 13 percent, according to the Kids Count report, which includes the latest youth employment data for every state, the District of Columbia and the nation.

“Over the last decade there has been a really dramatic decline in the number of young people who have jobs,” said Laura Speer, Casey’s associate director for Policy, Reform and Data. “There are more experienced adults lined up before them and they don’t have school or the experience of the typical first job.”

That means the problem began to surface even before we felt the effects of the recession.

Among young adults 20-24, only 60 percent have job experience, the report said. Among those 16-19, just one in four has had any employment experience, compared to 1 in 2 in 2000.

“Three out of four teens are not getting that early job experience, the skills that you learned in that first job, of being on time, how to work in a team, problem solving without your parents’ help, working with a boss,” Speer said.

With fewer low-skilled jobs available and the workforce becoming increasingly automated, it’s harder to find even menial jobs. Those jobs disappear and those who lack education and training won’t be ready to take any of the approximately 1.5 million better-paying jobs in the tech workforce that go begging in the U.S. because the nation’s workforce isn’t prepared.

Even the Republican Party platform acknowledged the education and skills gap. Its solution, however, was to propose “strategic immigration,” giving work visas to highly skilled foreigners who hold advance degrees in science, technology, engineering and math and encourage the new immigrants to become the job creators of the future—a signal, perhaps, that the party is throwing in the towel over ever getting Americans up to speed in a reasonable amount of time to keep the U.S. at the forefront of technological development.

Studies show, however, that those highly educated immigrants hone their skills here and ultimately take that experience back home to build businesses there and be with their families, Speer said.

Speer said the foundation would like to see the issue become a national priority.

Among its major recommendations:

• A national youth employment strategy that streamlines systems and makes financial aid, funding and other support services more accessible and flexible; encourages more businesses to hire young people; and focuses on results, not process.

• Aligning resources within communities and among public and private funders to create collaborative efforts to support youth.

• Exploring new ways to create jobs through social enterprises such as Goodwill and microenterprises, with the support of public and private investors.

• Employer-sponsored earn-and-learn programs that foster the talent and skills that businesses require — and develop the types of employees they need.

“No one sector or system can solve this problem alone — it demands a collective and collaborative effort,” Patrice Cromwell, director of economic development at the Casey Foundation, said in a statement. “Businesses, government, philanthropy and communities must work together with young people to help them develop the skills and experience they need to achieve long-term success and financial stability as adults.”

Jackie Jones, a journalist and journalism educator, is director of the career transformation firm Jones Coaching LLC and author of “Taking Care of the Business of You: 7 Days to Getting Your Career on Track.”