The man who police say tossed a Queens man onto New York City subway tracks, killing him, has confessed to the act, according to police, but most of the attention in the case has focused on whether the photographer who snapped the shocking photo of the man seconds before his death could have helped to save him instead of capturing his image and selling it to the New York Post.

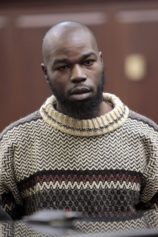

Ki-Suck Han, 58, of Elmhurst, Queens, was pronounced dead soon after being struck by the Q train at 49th Street and Seventh Avenue. Witnesses say he got into an argument with a man later identified as Naeem Davis, a 30-year-old street vendor, who had been mumbling to himself and harassing other passengers. Han was trying to tell Davis to leave people alone when he paid the ultimate price for getting involved.

It’s going to be a difficult lesson for New Yorkers, who are always debating with themselves whether to step in and get involved when something unpleasant is happening in front of them. It may also make subway rides even more unpleasant for black men in New York for the foreseeable future, as they may find themselves standing on a lot of empty subway platforms after fellow riders move away.

But the person who appears to be receiving the brunt of the public’s disgust—in addition to the perpetrator of the crime, who has yet to be charged by police—is the freelance photographer, R. Umar Abbasi, who says he tried to alert the oncoming train by fluttering his flash on and off but who still had time to snap several pictures of Han just before the train killed him. The Internet was ablaze with condemnation for Abbasi for stopping to shoot the pictures instead of trying to hoist the man back onto the platform.

There were also attacks on the New York Post, long known for trying to provoke as much controversy and attention as possible, for publishing the picture with the headline: “Doomed…Pushed on the subway track, this man is about to die.”

A Twitter critic questioned why Abbasi’s first instinct would be not to help the man, but instead to “snap a photo of him about to die and sell it to the NY Post.”

Abbasi didn’t help his cause when he told CNN he would speak to the network only if they paid him.

Somebody who did try to help Han was Dr. Laura Kaplan, a medical resident at Beth Israel Medical Center who was standing on the platform during the incident. According to a statement released today by her medical practice, she rushed to give Han aid after he was hit.

“A security guard and I performed 3-4 minutes of chest compressions. I hope the family may find some comfort in knowing about the kindness of these good Samaritans, as they endure this terrible loss,” Kaplan said in her statement.

“I would like the family to know that many people in the station tried to help Mr. Han by alerting the subway personnel,” she said.

Kaplan said she wanted to console the family of Han, who she called “a brave man trying to protect other passengers that he did not know.”

The perpetrator fled the scene into Times Square after the incident. He was described by police at the time as a 6-foot-tall, 200-pound black man wearing dreadlocks in his hair. He was picked up on 50th Street near Seventh Avenue by a transit police captain, who ran over to nab him while on a coffee break at 1:30 p.m.

Media experts addressed the question of whether the Post had gone too far—a question that has frequently been asked regarding the decision-making of the Post.

“Even if you accept that that photographer and other bystanders did everything they could to try to save the man, it’s a separate question of what the Post should have done with that photo,” Jeff Sonderman, a fellow at journalism think tank the Poynter Institute, wrote on the organization’s website. “All journalists we’ve seen talking about it online concluded the Post was wrong to use the photo, especially on its front page.”

Kenny Irby, Poynter’s senior faculty member for visual journalism and diversity programs, said what the Post did wasn’t unethical but was in poor taste.

“It was not illegal or unethical given that ethical guidelines and recommendations are not absolute,” he said in an e-mail to CNN.

“This moment was such for me—it was too private in my view,” he wrote, suggesting maybe another photo could have been chosen. “I am all for maximizing truth telling, while minimizing harm, which can be done by fully vetting the alternatives available and publishing with a sense of compassion and respect.”