Africa is a growth market for the world’s best-known Cuban brand after Havana Club rum and Cohiba cigars.

That would be Cuba Rx, also known as Havana’s doctor diplomacy.

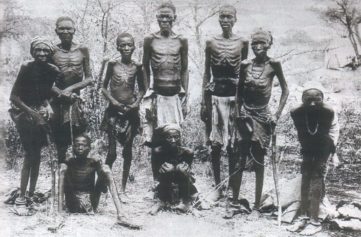

A generation ago, Fidel Castro sent Cuban soldiers to intervene in African civil conflicts and fight the Cold War against US proxies. Now, Cuba’s doctors are fanning out across the continent as the island expands its role in administering medical services to some of the world’s most ailing countries.

For Cuba the effort is good philanthropy, good diplomacy and, in some cases, good business. The Cuban missionaries are part of a widening global medical outreach that has boosted Havana’s ties around the world and earned billions in hard currency for the cash-strapped Castro government.

The largest contingent of Cuban doctors working abroad remains in Venezuela, Cuba’s closest ally, where they have helped boost support for Hugo Chavez’s government by staffing clinics in rural areas and rough neighborhoods where health services are scarce.

In turn, the Venezuelan government sends Cuba billions in cash as well as critical supplies of oil. But Chavez is facing re-election in October as well as an uncertain recovery from an aggressive and still-undisclosed form of abdominal cancer.

If a leadership change in Venezuela were to cool relations with Cuba, thousands of Cuban doctors could be reassigned elsewhere — many to Africa, where fast-growing economies and rising commodity prices have left some governments flush with cash yet lacking in health care professionals.

Some 5,500 Cubans are already working in 35 of Africa’s 54 countries, Cuban Foreign Ministry official Marcos Rodriguez told reporters this week at a press conference in Havana.

Of those, 3,000 are health professionals, and 2,000 are doctors, he said.

“We have blood ties with Africa,” the deputy minister said.

Some 1.3 million African slaves were brought to Cuba during the island’s colonial period, Rodriguez said, and 2,289 Cubans died fighting in Angola between 1975 and 1990, where some 300,000 Cuban served.

“Cuba believes that it has a historic debt to Africa that must be repaid,” he said.

Then again, Cuba’s debt repayment is not an entirely one-way affair.

While Cuba sends physicians to Africa’s poorest countries and grants scholarships for their students to study medicine on the island, it does a brisk business with more prosperous countries on the continent — especially those that are rich with oil and poor in health professionals.

Petroleum-pumping Africa nations such as Algeria and Angola are paying hefty sums to staff their hospitals with Cuban doctors, with most of the money going to the Cuban government.

For instance, the Angolan government pays Cuba about $5,000 a month for each doctor the island sends, according to a source with knowledge of the arrangement. The Cuban doctor receives a $500 share.

It’s a tiny cut, but the amount is still about 10 times what Cuban doctors can earn back home. The Castro government also rewards physicians who complete medical “missions” with other perks — like the ability to buy a used car from the state.

The specific details of each arrangement between Cuba and the countries that receive its doctors and other professionals are not public. But the programs seem to work along three basic channels: providing medical help free to poor countries that can’t pay, charging countries that can pay, and training medical professionals at universities back in Cuba.

This sliding-scale policy has won Cuba friends around the world, as students from more than 100 countries have been trained at the island’s medical programs. According to a report this week in the Toronto Star, nearly 20,000 foreign students are currently receiving medical training in Cuba — including 116 Americans on scholarship.

But not all foreign students are studying in Cuba for free. When officials in Ghana announced recently they had reached a deal with the Castro government to train 250 doctors over a six-year period, the arrangement was criticized by Ghanan officials who argued the money would be better spent boosting education doctors back home.

Many African doctors who train abroad opt to work in foreign countries where salaries are higher, and the Cuba’s training urges them to serve their communities back home.

After the 1959 Cuban Revolution, Africa was one of the first places Cuba’s health missionaries went when a small medical brigade arrived in Algeria following the country’s anti-colonial fight against France. Cuban medical personnel also accompanied Cuban soldiers sent to aid leftist allies in Angola, Namibia and elsewhere.

And the ideological battle between the US and Cuba is still playing out on African soil. A program created by the Bush administration in 2006 creates special visas for Cuban medical personnel who wish to defect from their missions abroad.

About 800 doctors have done so to date, drawing fierce criticism from the Castro government, which says the US visa program deprives poor countries of desperately needed medical care.

Source: Global Post