Africa — the cradle of civilization — has borne witness to many a false dawn. The continent has known profound eras of world influence and notable periods of decline. As humanity’s initial habitat, Africa is necessarily the originating situs of economic enterprise. Agrarian activity in Africa began around 5200BC, and the continent’s first movements on the global trade chessboard trace back to 3000BC. Trade incubated the growth of cities and empires such as the ancient Egyptian civilization, which left an indelible imprint on the story of human development.

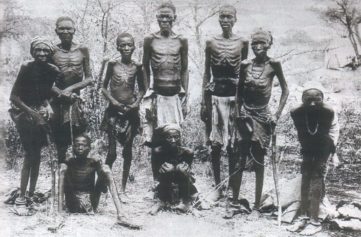

Events of the past 400 years have served to cast a shadow on Africa’s potential in the current world order. Half a century after attaining independence, the legacy of slavery and colonialism — undeniably a monumental economic benefit to then-emergent Western powers — still reverberates as a lasting curse that militates against Africa’s pursuit to rediscover its identity and find its footing on the floor of the dictates of global capitalism.

The 19th century colonial scramble for Africa struck at the heart of the region’s promise. Its caption amounted to the execution of a flawed imperial code of partition that saw the continent divvied up like a piece of cake, albeit with little method or due process. This led to arbitrary borders and later the creation of nation-states that bandied together diverse peoples who had no choice but to learn to co-exist beneath the same banner. Due to this wavering foundation, Africa’s development since the independence of its member states has, over the years, returned pessimistic ratings of progress.

Yet, there is more than enough blame to go around. Upon independence, the political architecture of many African states was held hostage by dictatorial regimes led by despots. Their rule was further fuelled by Cold War considerations. During the Cold War era, Africa was a pawn caught between the ideological divide of capitalist and communist-leaning nations. In their attempts at swaying African states to side with their campaigns, both sides turned a blind eye on the excesses of the despots. They instead bolstered their tyranny by providing aid while eschewing accountability.

The consequence has been oppressive rule, myriad internal and external conflicts at severe human cost, impoverished citizenry, and weak economies hemorrhaging resources through wastage and pillage. The catalyst for such detrimental governance has been political overreach, anemic democratic enculturation, weak constitutional institutions devoid of constitutionalism and fidelity to the rule of law, non-cognizance of human rights, and poor economic policies.

Howbeit, the winds of democratization and change would not be denied. The end of the Cold War allowed the din of pro-democratic voices to echo around the world. Western powers took heed, and in support of progressives, began pegging aid to the reform agenda. This precipitated an improvement in governance, with the ‘90s heralding the move by many African states from single-party dictatorships to multiparty democracies.

As goes the political foundation, so follows the economic narrative. Africa’s turbulent post-independence political situation was fodder for experimental economic policies inspired by the West. The Structural Adjustment Programs prescribed by the World Bank and IMF in the ‘80s, created Africa’s ‘credit crisis’ moment. The programs spurred initial economic decline as common citizens bore the brunt of escalating prices for goods and services, following privatization and deregulation in industries thitherto nationalized and subsidized by their governments.

Things would however get better. An overall decline in conflicts, the implementation of governance reform, the embracing of neoclassical free market economic ideologies, and the shift in emphasis from aid to foreign direct investment, impelled great economic advancement in Africa over the last two decades.

China’s mercurial rise has also had a visible effect on the continent. Many African countries have turned east for aid and developmental partnership. China’s appeal is its non-confrontational approach where it broaches less stringent requirements for assistance than does the West. Whereas China’s hear-no-evil-see-no-evil policy on African internal affairs may serve to reverse democratic gains, the China-Africa relationship has spurred discernible economic development, especially in infrastructure.

How is this relevant?

Developments over the last two decades cited herein, and the cross-pollination of ideas through the rapidity of globalization, have made Africa an appealing investment destination.

The African Union (AU) and other regional arrangements have fostered economic and political integration. Despite intermittent hangovers from the days of the moribund Organization of African Unity where the outfit served as an Old Boys Club to legitimize and protect the indiscretions of wanton dictators, the AU has marshaled efforts in the reduction of conflicts, the tearing down of trade barriers for a wider market for goods and services, and the promotion of the democratic agenda.

Africa was largely unaffected by the severity of the credit crises in the East and West and this has obliged even the most cynical of investors to take a glance at the continent. The optimistic environment for investment is further sautéed by the abundance of Africa’s natural resource wealth — and it is plausibly the richest region on the planet.

– By Samuel Ollunga

Read the rest of this story on Fairobserver.com