Toni Morrison never liked that old seventies slogan “Black is beautiful.” It was superficial, simplistic, palliative—everything her blinkered detractors called Morrison’s complex novels when the 1993 Nobel Prize transformed her into a spokeswoman and a target. No better were those blinkered admirers who invited themselves to touch her signature gray dreadlocks at signings, as though they harbored some kind of mystical power.

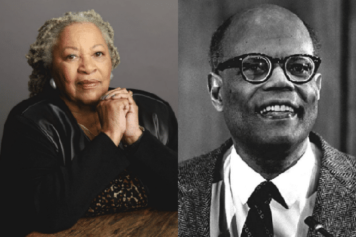

Still, even at 81, sporting both a new novel and a new hip, Morrison is as grand as she’s ever been. When we meet in her many-gabled house in the aptly named village of Grand View-on-Hudson, about 25 miles north of Manhattan, that bountiful woolen hair matches the lower half of a soft, enveloping sweater. Her face is polished in places and fissured in others, like the weathered stone of Mount Rushmore: the first black woman Nobelist, who’s lived long enough to speak to the first black president. Born only two years after Martin Luther King Jr., she’s a great-grandmother of assimilation—and she looks the part.

Morrison’s voice is as layered and visceral as her writing. The author growls, purrs, giggles, and barks. Discussing politics, her voice rises in indignation before cresting and breaking into a loud chuckle. (“They should have that in the military, or the prisons—a little affirmative action! Let’s bring some white guys in!”) She surrenders to a wheezing, shoulder-shaking, freight-train laugh when describing a particularly gruesome Funny or Die video. She booms theatrically in recounting the ghost stories her parents would tell every night. (“Sharpen my knife, sharpen my knife, gonna cut my wife’s head off!”)She slows to a pedagogical rhythm while discussing her “invisible ink”—symbols and allusions in her work that would be picked up only by a deep reader, or maybe someone writing a dissertation twenty years from now. And in more confessional moments, Morrison reverts to a register that’s gotten stronger with age, a husky but girlish whisper imparting both vulnerability and authority. That’s how she broaches, gingerly, the death of her son Slade, sixteen months ago, at 45, “which has clouded everything, everything, everything, everything,” she says. “It’ll be with me like a shroud, or a cape, forever.”

Read the rest of this story in New York Magazine