Thousands of opposition party supporters march on the streets of Harare, Wednesday, July 11, 2018.(AP Photo/Tsvangirayi Mukwazhi)

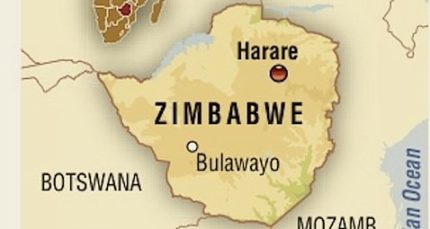

HARARE, Zimbabwe (AP) — The world’s oldest person is 141 years of age and lives in Zimbabwe. Not far behind is a 134-year-old, also in Zimbabwe. At least that’s according to the country’s voters’ roll, which has come under sharp scrutiny ahead of the July 30 election, the first in decades without longtime leader Robert Mugabe.

The main opposition party has called the voter roll deeply flawed and the most prominent sign that the election’s credibility is at risk. On Wednesday, thousands of people rallied in the capital, Harare, to call for more transparency, dancing and waving signs saying “No reforms, no elections.”

While President Emmerson Mnangagwa, who took power when Mugabe was pressured to step down in November, and the election commission have pledged a free and fair election, the issues with the voter roll have many worried that Zimbabwe’s government is failing to break with a long past of alleged election fraud.

The strikingly old voters are just one concern. The voter roll also shows more than 100 people registered at a single address and has multiple people sharing a single ID number, according to the main opposition’s chief election agent, Jameson Timba.

“We are not going to compromise,” main opposition leader Nelson Chamisa told the crowd on Wednesday, accusing the election commission, the military and Mnangagwa of trying to rig the vote. Chamisa is in a coalition with several smaller parties that also took part in the rally, delivering a petition with their demands to the election commission’s office.

“Next time we hold a demonstration, no one is going back home until our demands are met. We will camp here,” Chamisa said.

The opposition’s suspicions extend to the ballots’ printing, storage, design and even paper quality.

Confidence in the election has run so low that the opposition encourages its supporters to carry their own pens into the voting booths because they don’t trust the ones provided.

Mnangagwa, a longtime ally of Mugabe until he was fired as a result of a ruling party feud, is under pressure to deliver a free and fair election as a key step in lifting years of international sanctions.

Zimbabwe’s past elections have been marked by accusations of violence and fraud. Mugabe banned Western election observers but Mnangagwa has welcomed them for the first time in almost two decades. Observers from the European Union and the United States have raised concerns that are similar to the opposition’s although, in a break from the past, this year’s election has been largely free of violence.

Mnangagwa, his ruling ZANU-PF party and the election commission are defending the credibility of the vote. The electoral commission chairwoman, Priscilla Chigumba, has rebuffed the opposition’s demands, which include touching the ballot paper or examining it closely. Party representatives were allowed to view the ballot printing process from a distance last month, she said.

People had to watch from about 10 meters away, said another opposition candidate, Noah Manyika.

Political parties physically inspecting the ballot paper is unlawful, Chigumba, a former High Court judge, told reporters on Monday, calling the opposition demands “an abuse of the right to transparency.”

The election commission chairwoman also has denied problems with the voter roll, which was released to opposition parties and the public only after pressure and a court ruling.

The commission has said any mistakes in the roll are being corrected. The case of the single address with more than 100 registered voters “is in fact a church shrine with 122 voters,” Chigumba said.

Winning confidence in the remaining weeks before the vote will be a challenge. According to a survey released over the weekend by the Zimbabwe Council of Churches, 58 percent of registered voters do not trust the elections commission. The churches surveyed more than 1,600 people from Bulawayo, an opposition stronghold, and Midlands province, which has a mix of opposition and ruling party supporters.

While Mugabe is gone, “the regime remains,” said Munyaradzi Gwisai, a political analyst and law lecturer at the University of Zimbabwe. “If anything, the hard men and hard women of that regime are the ones who have taken power and they are now in charge, so very little has changed.”