Sadly, for too many African-American mothers, all does not go well. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, African-American mothers are nearly four times more likely to die during pregnancy and childbirth than are white women.

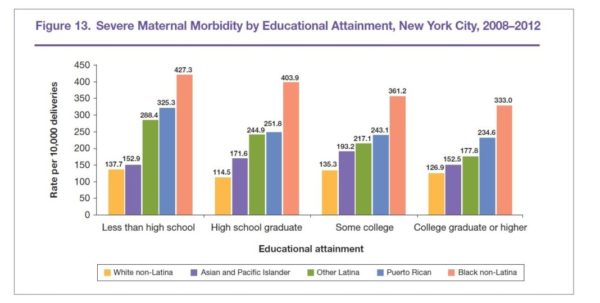

Although the racial disparity in maternal deaths has been studied for decades, the causes of the disparity are not clear. Factors that normally help to partially explain some race-related health disparities — income, poverty, education, and the like — are useless to explain the difference in maternal mortality rates. A study of mothers in New York City found that college-educated African-American mothers were more than three times as likely to suffer severe complications during birth than white mothers who had dropped out of high school.

Source: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (2016).

Severe Maternal Morbidity in New York City, 2008–2012.

A recent CDC paper on maternal mortality reports that some 700 women in the United States die from pregnancy-related causes each year. The report defines a pregnancy-related death as one that occurs during pregnancy or within up to one year after the pregnancy from conditions or complications that arose during the pregnancy. Thirty-eight percent of deaths happen during pregnancy, 45 percent come within 42 days of birth, and the remainder occur up to year after delivery.

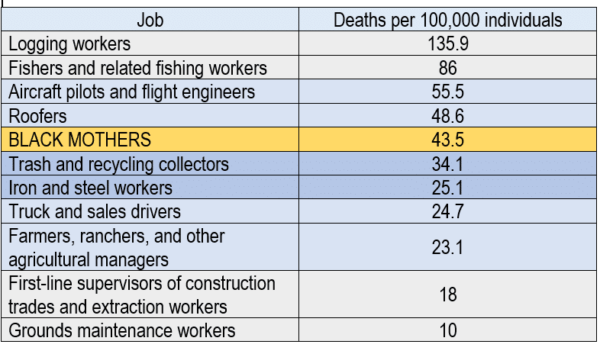

In highlighting the racial disparities the data reveal, the paper’s authors said African-American women “experience maternal deaths at a rate three to four times that of non-Hispanic white women.” Indeed, the most recent CDC data show that while there are 12.7 deaths per 100,000 live births for white women, there are 43.5 deaths per 100,000 live births for black women. To put this into perspective, if being a pregnant Black woman were an occupation, it would be the fifth deadliest job in the country. For a Black woman, becoming pregnant in the 21st century is more dangerous than being a steel worker or working on a construction site.

Graphic by author with data from the Centers for Disease Control and Time Magazine. http://time.com/5074471/most-dangerous-jobs/

What accounts for the wide disparity in outcomes between Black and white mothers? The place to begin might be the causes of death. For white mothers, the top five causes of maternal death, in order, were cardiovascular conditions, hemorrhage, infection, mental health conditions, and cardiomyopathy. For Black mothers, cardiomyopathy was the leading cause of death, followed by cardiovascular conditions, preeclampsia and eclampsia, hemorrhage, and embolism. While the causes are slightly different and may be ranked differently, there is significant overlap. Indeed, a 2007 study by researchers from the CDC found that pregnancy-related complications and conditions such as preeclampsia, eclampsia, and hemorrhage were generally equally prevalent in white and black pregnant women. But the study also found that Black women were two to three times more likely than white women to die from one of these conditions. In sum, Black women generally face the same pregnancy challenges as white women, but they are more likely to die when they confront them.

The Center for Reproductive Rights study noted that due to poverty, lack of insurance, and other factors, “low-income and uninsured Black women are already at high risk for maternal death by the time they become pregnant. Compared to white women, women of color fare significantly worse in key general health indicators, including diabetes, obesity, heart disease, and hypertension. These poor health indicators are often exacerbated during pregnancy, especially if they remain untreated, and are a driving force behind preventable maternal deaths.”

Dr. Tyan Parker Dominguez, a clinical professor and vice chair of curriculum for children, youth, and families at the University of Southern California, agrees. In an interview with Atlanta Black Star, she stated, “Pre-existing medical conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and autoimmune disorders (e.g., lupus), can increase the risk for adverse maternal outcomes. Hypertension during pregnancy — pre-eclampsia/eclampsia — can lead to seizures or stroke. … The incidence of health issues such as hypertensive disorders and infections is higher in African-American women.”

While pre-existing conditions are part of the issue, they are only one piece of the puzzle. Indeed, Dr. Parker Dominguez also noted, “The disparities are long-standing and research shows they are not due to traditional risk factors, prompting many to consider long-standing social inequity a fundamental driver of these population health differentials.” She further explained that when she first began this work, she was “surprised to learn that higher incomes and better education did not seem to decrease African-American women’s risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes. That is paradoxical to the prevailing evidence that socioeconomic status is strongly linked to health.”

Dr. Jameta Barlow, a community health psychologist and assistant professor at Towson University, also spoke with Atlanta Black Star. She concurred with the assessment. “Black women across all socioeconomic classes experience increased rates of not only maternal mortality, but also infant mortality and low infant birth weight. Typically, class can be a predictor of health; however, in this case, the … phenomena all of these women share [are] their intersectional experiences of living while Black and woman in the United States.”

Dr. Rachel Hardeman, assistant professor in the Division of Health Policy and Management at the University of Minnesota also spoke with Atlanta BlackStar about this issue. On this point, she offered the real-life example of Serena Williams. Williams, a wealthy, world-renowned tennis player, faced many difficulties after her daughter was delivered via caesarean section. In an interview with Vogue magazine, Williams said that after feeling short of breath she believed she was suffering a pulmonary embolism. According to the article, “She walked out of the hospital room so her mother wouldn’t worry and told the nearest nurse, between gasps, that she needed a CT scan with contrast and IV heparin (a blood thinner) right away. The nurse thought her pain medicine might be making her confused. But Serena insisted, and soon enough a doctor was performing an ultrasound of her legs. ‘I was like, a Doppler? I told you, I need a CT scan and a heparin drip,’ she remembers telling the team. The ultrasound revealed nothing, so they sent her for the CT, and sure enough, several small blood clots had settled in her lungs. Minutes later she was on the drip. ‘I was like, listen to Dr. Williams!’” This event triggered a saga of events that resulted in weeks of evaluations, surgeries, and recovery.

When Williams tried to tell the hospital staff about her condition, their first response was to downplay her concerns. Sadly, this scenario is all too familiar for many Black women. The 2018 CDC report notes that over half of maternal deaths are preventable, and that provider error — including failure to diagnose — is a key factor in these cases. Therefore, it is critical that doctors listen to their patients’ complaints and concerns. But racial bias among health providers may prevent Black women’s voices from being heard.

Dr. Hardeman said, “There is a vast body of research linking implicit racial bias to clinical decision making. Implicit bias and stereotyping can lead to misdiagnosis. I also think that we have to consider the racial narratives around black women and birth. While providers may not explicitly be drawing on them, they have been socialized to think about black women in specific ways which implicitly and sometimes also explicitly allow them to misdiagnose or underestimate pain levels.”

Finally, despite her wealth and fame, Ms. Williams is still an African-American woman. Systemic racism plays a key role in undermining Black women’s health in multiple ways. Structural racism plays a role. Dr. Barlow saide, “Structural racism and segregation are inextricably linked to access to poor resources, such as healthy grocery stores, hospitals with adequate technologies, etc.”

Because Black maternal mortality is a complex problem caused and aggravated by many different factors, it may seem that the problem is unsolvable. The good news is that there is hope.

Vox reported that North Carolina has eliminated the racial disparities in maternal deaths. The state achieved this by giving special financial incentives to doctors treating Medicaid patients. The doctors were encouraged to screen for issues that might make a pregnancy high-risk, and to refer high-risk patients to a “pregnancy care manager,” a person who helps the patient remain healthy throughout her pregnancy. Programs like North Carolina’s demonstrate that solutions are possible and Black mothers’ lives can be saved.

In the end, while the challenges facing Black mothers in the delivery room — and after — are daunting, they are not insurmountable. As the experts stated, work must be done at all levels of government and on all levels of patient care to improve outcomes. The problem is solvable, and we must solve it. No Black mother should have to sacrifice her life to bring a life into the world.