Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder can create emotional, social, and educational problems for children with the disorder. ADHD often leaves African-American parents of affected children fighting many battles simultaneously. On one front, the parents of African-American children with ADHD fight to get their children proper diagnoses and treatment. If successful, those parents are invited to the next battle: getting their child the necessary help.

There is also a fear that the diagnosis is not the pathway to help but the actual problem. Racism causes some Black children to be over-diagnosed with ADHD, tracking of Black children causing lower academic achievement and over-medication.

Few diseases are as misunderstood as ADHD (sometimes also referred to as ADD, or Attention Deficit Disorder). Some go so far as to argue that ADHD does not exist. However, there is broad agreement in the medical community that ADHD is a real disease.

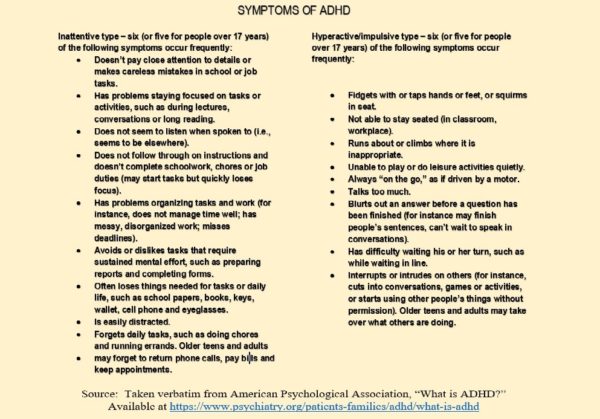

According to the American Psychological Association, there are three types of ADHD: inattentive type, hyperactive/impulsive type or combined type. In the inattentive type, the child, has difficulty staying focused on tasks. In the hyperactive type, the child seems as if she is in perpetual motion; it appears that the child cannot slow down, even when she tries to do so. Children in the third category will display both types of behaviors at different times.

Some adults are skeptical about ADHD because most children are hyperactive at some point during the day. Although all children daydream or play at inappropriate times, a child will not be diagnosed with ADHD unless she displays at least six hyperactive or inattentive characteristics. Also, she must display these characteristics more strongly than other children her age and do so regularly for a minimum of six months. Moreover, the behaviors must be displayed in multiple locations (e.g., at home and at school) to support an ADHD diagnosis.

Another factor that contributes to the misunderstandings around ADHD is that its causes are unclear. According to the APA, while the exact cause or causes of ADHD have not been identified, heredity is a key factor, as three of four children with ADHD have a family member with ADHD. The APA states that issues arising during pregnancy and birth — such as prematurity, maternal stress, and alcohol or drug use during pregnancy — are also factors. According to Health magazine, there is evidence that exposure to certain environmental factors such as pesticides and lead-based paints may play a role.

Due to the confusion surrounding ADHD, it is important to note that some of the things commonly believed to cause ADHD do not contribute to the disorder in any way. The same Health article notes that, contrary to popular belief, a child’s diet does not cause ADHD. Specifically, sugar does not cause ADHD. Similarly, bad parenting does not cause ADHD. Finally, television, video games, and tablets have nothing to do with ADHD.

Yet another factor that contributes to the mystique of ADHD is how it’s diagnosed. Although ADHD causes changes in the brain that can be measured, these tests are costly and difficult. As a result, the APA notes that ADHD is usually diagnosed using a series of questionnaires. Adults that know the child well — teachers, parents, and other caregivers — will answer questions about the child’s behavior. Based on the results, a doctor will determine a diagnosis.

Once diagnosed, there are two primary treatments for ADHD — therapy and medication. The medications prescribed for ADHD are generally in the stimulant class. Stimulants allow the child to focus when needed. Drug treatments become controversial because some doctors and parents object to giving young children daily doses of powerful medications. However, most experts agree that children do best when they take their medication and their parents make the modifications recommended during therapy sessions.

Some believe that ADHD is real, but do not believe that it causes significant problems. In reality, children and teens with ADHD must confront academic, emotional, and social challenges.

According to data compiled by The ADHD Institute (“the Institute”), children with ADHD may have lower educational achievement. In a typical scenario, because these children are easily distracted, they are more likely than others to complete their homework in a sloppy fashion. Then the teacher might not see the messy homework because it gets lost before it’s turned in. Per the institute, these issues, if left unaddressed, can impact school performance and even school completion.

Moreover, the Institute’s data shows that students with ADHD have issues adjusting socially. Because these children are inattentive and impulsive, social graces do not come easily. As a result, they are more likely to have trouble making and keeping friends. They are more likely to argue with peers and family members.These effects often create higher stress levels for parents of ADHD children than parents of unaffected children.

According to the Institute, impulsive children with ADHD may have greater difficulties in evaluating risks and accepting delayed gratification. Being able to evaluate risk and reward is essential to following rules, which is another area where children with ADHD may struggle.

While children with ADHD face many concerns, the most significant concern is that children with ADHD grow up to become adults with ADHD. If these children do not learn to manage their disorder at an early age, they may experience poor life outcomes. According to the Institute, just as children with ADHD struggle in school, adults with ADHD are less likely to finish their college degrees than those without the disorder. Moreover, just as children with ADHD struggle socially, adults with ADHD may find it difficult to make and maintain romantic connections. More troubling, their social difficulties can impact their work life. Most troubling of all, the impulsivity and desire to take risks associated with ADHD in children can translate into a higher likelihood of criminality in adults with ADHD. Other research notes that teens and young adults with ADHD may be more sexually impulsive or promiscuous.

It should be noted that these outcomes are not inevitable. Early and continued treatment for ADHD can improve these outcomes. Like most other health issues, race influences ADHD outcomes — although not in the way most African-Americans expect.

African-Americans are skeptical about ADHD. Research by Dr. Rahn K. Bailey, chair of psychiatry at Wake Forest University School of Medicine, found that, compared to whites, African-Americans are less familiar with ADHD and its treatments. Conversely, Blacks are more likely than whites to believe that Black children are diagnosed with ADHD at higher rates than other groups.

Black parents are not being unnecessarily paranoid. According to Dr. Bailey’s work, studies from the 1970s frequently found that students from schools with large African-American populations were more likely to be labeled as hyperactive than students from schools in white, middle-class neighborhoods. Many African-Americans are wary of the fact that most elementary school teachers are white women, so their views of Black behavior may be racially biased. However, as the APA states, “Teachers and school staff can provide parents and doctors with information to help evaluate behavior and learning problems, and can assist with behavioral training. However, school staff cannot diagnose ADHD, make decisions about treatment or require that a student take medication to attend school. Only parents and guardians can make those decisions with the child’s physician.” So, though teachers are an important piece of the ADHD puzzle, a teacher’s belief that a child is hyperactive is not an ADHD diagnosis.

Black parents’ suspicion regarding ADHD could also be rooted in the fact that Black children may be more likely to be put into special education courses. But ADHD itself is not a learning disability that automatically requires special-education placement. Children with ADHD can have learning disabilities, and some do. Other children with ADHD are gifted students. While Black parents and teachers should continue to resist efforts to railroad Black children who do not belong in special education, a child with ADHD will generally not face this issue unless he or she also has a learning disability.

There is yet another area of over-diagnosis. African American youth with ADHD are more likely than white students to be diagnosed with Conduct Disorder. CD is characterized by “a repetitive and persistent pattern of behavior by a child or teenager in which the basic rights of others or major age-appropriate societal norms or rules are violated.” Interestingly, African-American males with these characteristics are diagnosed with CD. By contrast, white males displaying the same behavior were likely to be diagnosed with ADHD.

African-Americans are over-diagnosed with other disorders or issues, when it comes to ADHD, under-diagnosis, and under-treatment are the issues. To obtain a diagnosis, parents and teachers must cooperate during the questionnaire process. Thus, on some level, there must be trust between the parents and teachers. However, as noted, racism in the education field has weakened that trust for many African-American parents.

The failure to properly manage ADHD can have particularly severe impacts for Black children, youth, and families. Dr. Bailey’s paper noted that untreated ADHD could contribute to higher drop-out rates for African-American students. Moreover, he mentioned that the connection between ADHD and sexual impulsivity should be concerning given the higher rates of certain sexual transmitted diseases in the Black community.

The most significant reason for Black parents to treat ADHD before it becomes a problem is school discipline. Black students with undiagnosed or unmanaged ADHD symptoms are unlikely to be treated sympathetically when they cause discipline problems. Research from Dr. Myles Moody notes that though these children have not been diagnosed, they still have the disorder. Their untreated behavior makes them susceptible to discipline. For Black students, the failure to treat ADHD may cause a child to enter the school-to-prison pipeline. Sadly, once in prison, Dr. Bailey notes that they will be unlikely to get the mental health services they require.

A key finding of Dr. Bailey’s research is that Black parents frequently do not know how ADHD works or how to get a proper diagnosis. But what a parent doesn’t know can hurt his child. Whether fighting for a diagnosis or fighting against one, knowledge is power. Parents are a child’s best advocates. Black parents must learn as much as they can about ADHD and other disorders to help their children avoid pitfalls and achieve success.