“In this country American means white. Everybody else has to hyphenate.”

— quote from Toni Morrison, Nobel and Pulitzer Prize-Winning Novelist

Recently, the killing of four U.S. soldiers in Niger made headlines. The story then became one about the current commander-in-chief’s response to the deaths. During his condolence call to the widow of Sgt. La David Johnson, Trump told Mrs. Johnson that her husband “knew what he signed up for.” Myeshia Johnson reported that Trump’s dismissive tone and failure to remember her husband’s name caused her to cry in anger.

The Johnsons are the not the first Gold Star family that Trump has feuded with publicly. After the parents of Capt. Humayun Khan spoke at the Democratic National Convention in 2016, Trump took to Twitter to claim that Khizr Khan, the fallen solder’s father, “viciously attacked” him.

Though Sgt. Johnson and Capt. Khan both volunteered to serve in this nation’s military and both made the ultimate sacrifice, their families were not treated with respect. Indeed, though they claim to be patriotic, Trump and many of his supporters do not see his actions as disrespectful.

The fact that Sgt. Johnson was African-American and Capt. Khan was Pakistani-American might explain the inconsistency.

Legally, according to the Fourteenth Amendment, every person born in the United States is an American citizen. However, Americans that are not white know that this principle holds up better in theory than in practice. In reality, non-white American citizens are seldom viewed as truly “American.” In study after study, researchers have found that most whites believe the ideal American is also white. Why is this so?

Dr. Thierry Devos, professor of psychology at San Diego State University, has written or co-authored several articles on this phenomenon. His paper “American=White?” studied the connections people made between a person’s race and that person’s perceived “Americanness.” Participants were tested for both conscious and subconscious bias. No matter the method, the tests showed that overall, African-Americans are not viewed as American by whites.

African-Americans are not the only group affected by this particular type of racism. Latinos and Asian-Americans are also viewed as less American than whites. In fact, according to Dr. Devos, “Latino and Asian-Americans are the two groups most strongly excluded, followed by African Americans.” Latinos and Asian-Americans are treated as “perpetual foreigners,” and often asked questions such as “Where are you really from?” or complimented for speaking perfect English.

When asked to explain these findings, Dr. Devos stated, “There is a form of mental hierarchy regarding who is seen as a ‘true American’. The numerical status of these groups (majority vs. minority), their social status (who is more valued in society), their relative economic and political power, the length of immersion of these groups in American society are factors probably contributing to this phenomenon. These factors almost consistently favor White Americans.” Moreover, he noted that these associations “are a window into the structure of a society that remains characterized by strong inequalities in terms of power, status, and representation. What individuals see and pick up in their daily experiences being immersed in this society will tend to foster a conflation of whiteness and Americanness.”Dr. Devos noted that “the implicit American = White effect was quite strong, robust, and pervasive.” To illustrate, he said, “Even a well-known American actress such as Lucy Liu is sometimes seen as less American than a white foreigner such as Kate Winslet. These findings show that the White=American linkage is so deeply ingrained that we cannot eradicate it even when our conscious beliefs say otherwise.”

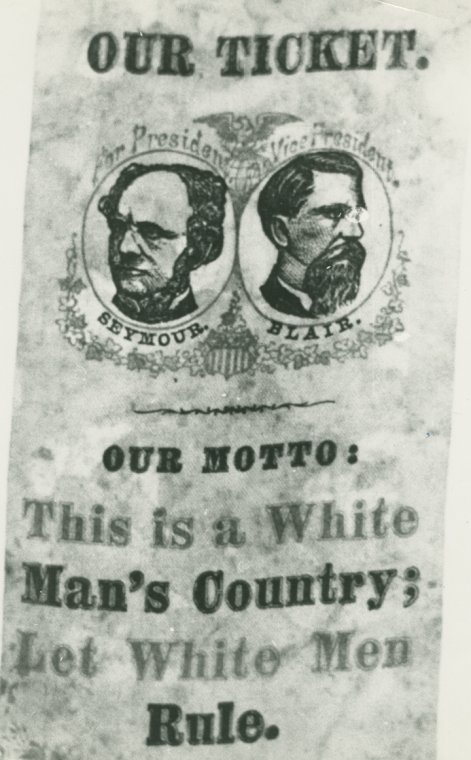

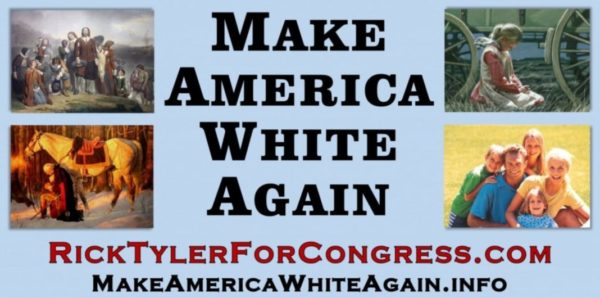

The failure to see non-whites as fully American has real ramifications for non-whites in politics and policy. Whites who feel threatened by non-whites gaining freedom, power, authority, or autonomy seem to turn to slogans that urge America’s return to whiteness. In the 1868 presidential elections, the first presidential elections after the Civil War, Horatio Seymour ran using the slogan “This is a White Man’s Country; Let White Men Rule.” Although he lost the election, nearly 150 years later, a man sailed to victory using the slogan “Make America Great Again,” which many people believed was a call to “Make America White Again.”

Flyer from the 1868 campaign of Mr. Horatio Seymour.

Source: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/62a9d0e6-4fc9-dbce-e040-e00a18064a66

Billboard from 2016 Congressional Candidate Rick Tyler

Source: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2016/06/23/make-america-white-again-a-politicians-billboard-ignites-uproar/?utm_term=.c59c8432ff85

This form of racism impacts policy as well. Researchers from the University of Massachusetts tested white students to determine how closely they linked whiteness with Americanness. They then asked the students to read a hypothetical op-ed arguing that America should admit more skilled immigrants. The students were then told that the writer was either white or Asian. The students who most closely connected Americanness to whiteness were most likely to reject the proposal when the writer was Asian. So, linking whiteness to American identity prevents whites from hearing African-Americans, Latinos, or Asian-Americans in the policy sphere.

The need for whites to conflate the American identity with whiteness had an impact on the presidency of Barack Obama. According to Dr. Devos, “People who had a difficulty associating the American identity with Barack Obama were less likely to express a willingness to vote for him.”

Other research confirms that not only did these persons not vote for him, they refused to support him. Dr. Eric Hehman of Ryerson University in Toronto surveyed whites about their racial attitudes and their views of Obama’s Americanness one year into his presidency. The study concluded that “bias in viewing Blacks as less American than Whites appeared to implicitly underlie Whites’ negative evaluations of Obama’s performance.”

Another facet of this problem is the personal effect it has on non-whites. Americans that are not white are well aware that many whites see them as less American. Dr. Devos stated, “The conflation of whiteness and Americanness manifests itself in all kinds of reactions or daily interactions. Members of ethnic minorities have to contend routinely with the assumptions that they are not fully American, that they are second-class citizens. This is not a trivial or benign experience, in particular when it occurs frequently and across many domains of life. It is an insidious message that is pervasive, yet hard to confront; it perpetuates marginalization.”

There is one last positive finding to note. Although whites may be unwilling to view Black people and other people of color as their fellows as American, non-white consider themselves patriotic. Perhaps African-Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinos are pushing America to give the American identity a definition that includes fairness and justice — not just whiteness — as key attributes.What can be done to change the American identity? Dr. Devos characterizes this issue as “complex” and not yet fully understood. However, he did note that because the definition of “American” is not fixed, change is possible. He noted that “the fact that the country is becoming increasingly diverse and multi-racial” could change the implicit meaning of Americanness for future generations in a way that benefits non-whites.

However, he cautioned, “At the same time, many other factors are likely to perpetuate inequalities and disparities between groups, making it challenging to consider, in our minds, that all groups making up the population are equally American.”