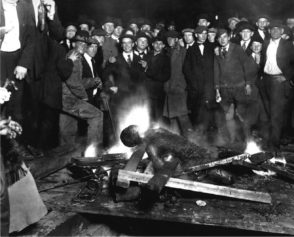

The Feb. 1, 1893, public lynching in Paris, Texas, of Henry Smith, a black man accused of raping and murdering a 4-year-old white girl. (Photo/Wikimedia)

Before police shootings and mass incarceration beset Black America, the grotesque specter of brutalized Black bodies terrorized communities throughout the South, which struggled to deal with the problem of lynching.

Lynching most often occurred in the South, though not exclusively. And while other ethnic groups fell victim to the extrajudicial killings, Blacks were common targets of white vigilantes. For many African-Americans who grew up in the 19th and 20th centuries, lynching served as a painful reminder that the end of the Civil War in 1865 did not mean they were totally free.

In a July 1914 editorial titled “The Cause of Lynching” in the NAACP’s The Crisis magazine, of which he was founding editor, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote: “It is exceedingly difficult to get at the real cause of lynching but The Crisis is more and more convinced that the real cause is seldom the one alleged.”

The Massachusetts native’s activism had been reawakened in 1899 by the well-publicized lynching of Sam Hose, who after killing his white employer in self-defense and being falsely accused of raping a white woman, was stripped naked, tortured and burned in front of a crowd of 2,000 near Atlanta, where Du Bois was a professor. He later reported seeing Hose’s knuckles in a jar displayed as a souvenir in a shop’s window.

In 2015, the Equal Justice Initiative, a Montgomery, Alabama-based social justice advocacy group, learned through five years of research and 160 visits around the South that even more Black people were lynched than previously thought. About 4,300 were lynched in a dozen Southern states between 1877 and 1950, it has found.

Since then, EJI has teamed up with Google to publicly share details of its research through a new “Lynching in America” website that will go live on June 13. It will feature interactive maps of reported lynchings and the Great Migration, oral histories and a short documentary film.

Prior to the website’s launch, members of the media were invited to get a first-hand look of the website at Google’s Atlanta office. Touch screens resembling life-size iPads and laptops located around a room became a gateway to one of America’s darkest periods.

A few finger swipes on a screen revealed, down to the county level, where 654 reported lynchings took place in Mississippi, 589 in Georgia and 549 in Louisiana. A few keyboard clicks showed how the country’s demographics, based on census data, were changed when 6 million African-Americans fled the South to other regions in part as a result of lynching. The website also includes classroom materials to help teachers educate students on the subject.

Bryan Stevenson, founding EJI executive director, joined the gathering via a video conference call and explained that the project is an effort to move the country forward by confronting the past.

“We’re not going to be free in this country because we haven’t dealt with all the challenges and burdens our history of racial inequality has created,” said Stevenson, a public interest lawyer who specializes in death penalty cases.

In a short film that appears on the website titled, “Uprooted,” an Oakland, Calif., woman named Shirah Dedman shared the tragic story of her great-grandfather, Thomas Miles Sr., a business owner, who was lynched by a white mob on April 9, 1912, near Shreveport, La., for reportedly passing a note to a white woman. He was hanged from a tree and his body riddled with bullets.

In one emotional scene during her journey back to her family’s roots in Louisiana, Dedman and other relatives hugged a tree that was possibly the site of her ancestor’s lynching. “Obviously it was not just us, it happened to many families,” she said.

Michael Pfeifer, a history professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, who has written extensively about lynching, said there is undoubtedly a connection between the acts of terror of the past and current problems in the criminal justice system.

“I have argued in my books that the death penalty and informal practices of racialized policing were shaped over many years, by lynching, and vice versa, as means of perpetuating criminal justice institutions that could preserve white supremacy as well as the white community’s emphasis on its participation in and determination of criminal justice,” said Pfeifer.

Google, which provided support for the Lynching in America website project, has helped fund a number of racial and social justice projects through its charitable arm, Google.org, since a white supremacist killed nine Black church members in Charleston, South Carolina, in June 2015.

Justin Steele, principal at Google.org, said he and his colleagues were inspired by a speech Stevenson had given earlier that year at a company meeting that challenged them to do more to advance racial justice.

Coinciding with the website’s launch, Google.org is donating $1 million to EJI to support its work. It has already provided the organization with a $1 million grant to help fund its national memorial to lynching victims and From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration Museum, on the site of a former slave warehouse. Both are expected to open in Montgomery in 2018.

“We’re really just scratching the surface,” said Stevenson.

“These communities, these descendants, these victims are all around you, and bringing their stories to light is one of the great challenges that we face at this time, and the need for achieving racial justice is even greater than that.”