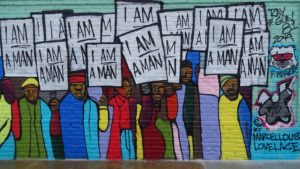

The “I Am A Man” mural is designed by rap artist Marcellous Lovelace in a modern graffiti style and installed by BLK75. It can be found on S. Main Street in Memphis, Tennesses, close to the National Civil Rights Museum. It shows the Sanitation Workers Protest March on March 28, 1968, an important event of the Civil Rights Movement, originally captured by photographer Richard L. Copley.

What will it take for African-Americans to gain their citizenship? Brought to the shores of this land for the sole purpose of hard labor and a permanent, inherited and inherent state of servitude, Black people never were meant to become citizens. And yet this is what happened on July 28, 1868, when the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was adopted. It was on that day that Secretary of State William Seward issued a proclamation in which he certified the ratification of the 14th Amendment by the states.

Since that time, it has been an uphill battle for the descendants of slaves to remove the badge of slavery, even when the physical shackles were removed. White racism has been the culprit, according to Professor Darren Hutchinson of the University of Florida Levin College of Law.

“The granting of citizenship was always fragile for blacks,” he told Atlanta Black Star. “The Black Codes gave rise to the amendment, but it could not prevent violence and general white supremacy. Only the federal troops proved effective at doing this. Once Reconstruction ended, the Amendments became aspirational more than anything else for more Black people,” said Hutchinson, who teaches Constitutional Law, Remedies, Race and the Law, and a Civil Rights seminar.

Malcolm X articulated the extent of the problem of citizenship for African-Americans in a 1963 interview, when journalist Louis Lomax pressed the issue.

“If they were citizens, you wouldn’t have a race problem. If the Emancipation Proclamation was authentic, you wouldn’t have a race problem. If the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution were authentic, you wouldn’t have a race problem,” Malcolm insisted. “If the Supreme Court desegregation decision was authentic, you wouldn’t have a race problem. All of this hypocrisy that has been practiced by the so-called white so-called liberal for the past 400 years, that compounds the problem, makes it more complicated, instead of eliminating the problem.”

Civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer said, “I am sick and tired of being sick and tired.” And Hamer wanted to become a “first-class citizen,” as she testified at the 1964 Democratic Convention as a founder of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, in opposition to her state’s whites-only delegation. She spoke of the beatings, harassment and threats she faced from white supremacists for attempting to exercise her rights as a citizen.

“Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off of the hooks because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?” she asked.

Black people in America are constantly made to fight for their rights, and are subjected to the whims of a hostile white majority. Being a citizen on paper and under the law proves illusory when the institutional racism against us has not abated.

New movements are necessary every few decades or so in order to secure the rights we were told we already have. And even today, there is a struggle among Black people, who are fighting for an existence free from state violence, mass incarceration and institutional racism.

True citizens are not subjected to arbitrary shooting deaths by police, voter suppression laws, or school-to-prison pipelines. And Malcolm X would note that if Black people were recognized as true citizens, there would be no need for a #BlackLivesMatter movement. This, as Donald Trump and other conservative politicians, responding to anti-immigrant, anti-Latino and xenophobic sentiment, have sought the elimination of birthright citizenship, which the 14th Amendment provides, resulting in an overturning of the 14th Amendment. Why is that so, and what would it take for people of color to be truly free, in reality, with the rights of full citizenship?

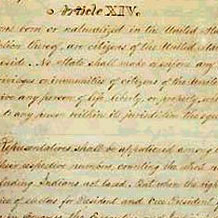

Section 1 of the amendment says the following:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

With the enactment of the 14th Amendment, the infamous Dred Scott v. Sanford decision — which held that the descendants of African people could not be citizens — was no more. In Dred Scott, Blacks, according to Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit. He was bought and sold and treated as an ordinary article of merchandise and traffic, whenever profit could be made by it.”

“The Citizenship Clause of the 14th Amendment guaranteed formal citizenship to ‘all persons born in the United States’ including African Americans. Of course, this is citizenship in name only,” Vinay Harpalani, Associate Professor at Savannah Law School, told Atlanta Black Star.

14th Amendment Document

Harpalani, an expert on affirmative action, race-conscious university admissions and equal protection, noted that the courts chipped away at the power of the constituent parts of the amendment.

“But the 14th Amendment did have promise to actualize the promise of citizenship, through the Privileges or Immunities Clause, Equal Protection Clause, and Due Process Clause. However, interpreting these broadly worded clauses was up to the courts. Soon after the ratification of the 14th Amendment, the U.S. Supreme Court, in the Slaughter-House Cases (1873) essentially narrowed the scope of the P&I Clause to the point where it was hardly applicable,” Harpalani said. “The Equal Protection Clause was also rendered largely irrelevant by Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which upheld the separate but equal doctrine. This did not change much until the New Deal and World War II eras, when the U.S. Supreme Court began striking down racial segregation — culminating in Brown v. Board of Education. But even this victory was short-lived,” he added.

“In its original conception, the 14th Amendment was an anti-subordination law designed to lift African-Americans out of slavery and allow them to be equal citizens. This requires remedial action ordered by the courts or passed by Congress (see Section 5). However, when the U.S. Supreme Court took a conservative turn in the 1970s, it began viewing the 14th Amendment as an anti-classification law, which meant that remedial actions designed to help African-Americans attain true citizenship became suspect. We saw this through the Court’s hostility toward desegregation and affirmative action,” Harpalani noted.

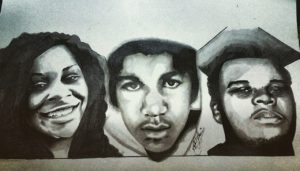

Sandra Bland, Trayvon Martin and Mike Brown (creativmind/tumblr)

Meanwhile, David S. Cohen, Professor at the Thomas R. Kline School of Law at Drexel University, reflected on the prospects of attaining full citizenship rights, what that would entail and the obstacles involved.

“Blacks and other people of color are going to have to fight for their rights as long as there is a substantial number of racists in this country and as long as one political party pretty much bases its party platform on continuing racial subordination. In other words, the Constitution and laws were changed, but not enough people’s minds were, and in a democracy, that’s a huge barrier,” Cohen told Atlanta Black Star.

Harpalani elaborated on what it would take for African-Americans to attain the full rights of citizenship.

“I do not know if that is possible: the late Professor Derrick Bell wrote about the permanence of racism. But if it is possible, it will take more than the courts to do it. Congress has to pass appropriate remedial laws, and the President has to be willing to fully enforce those laws. Unfortunately, that usually has not occurred, and social and political movements are helpful to make it happen,” he said. “But ultimately, I hark back to Professor Bell: African-Americans gain more citizenship rights when it serves the interest of white Americans. Slavery was abolished in part to promote the industrial future of America and steer it away from being an agrarian society. De jure segregation was eliminated because it was an international embarrassment after World War II, when the United States wanted to expand its global influence and, in the wake of the Cold War, to prevent African-Americans from being drawn to communism,” Harpalani added.

“So in my view, laws are not enough. Activism is not enough. But we need both laws and activism, and at the right historical moment, African-Americans will gain some more citizenship rights. It will not be full citizenship, and it is a slow climb — certainly not satisfying to advocates of racial justice. But this is the unfortunate reality in my view.”