Existing “Panda Brandywine” gas-fired plant in Brandywine. 1 of 5

Brandywine residents have filed a civil rights lawsuit against the state of Maryland, after officials approved plans for a new gas plant in their community. Brandywine is a 72-percent Black town in Prince George County Maryland.

The Maryland Public Service Commission granted Panda Power Funds a permit to build the 990-megawatt, gas-fired power plant last November. If completed, the proposed Panda Mattawoman plant will be the fifth plant within a 13-mile radius of the city, two existing and two proposed, the Baltimore Sun reports.

Earthjustice, the country’s largest nonprofit environmental law organization, filed complaints with the Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Department of Transportation on residents’ behalf May 11.

The claim cites Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prevents agencies receiving federal funds from discriminating on the basis of color, national origin, gender, disability or age. Attorneys argue the state is in violation for authorizing construction of a plant that will have “an unjustified disproportionate adverse impact” on the African-American population.

Fred Tutman is founder and CEO of Patuxent Riverkeeper, an organization that maintains conditions along the tributary, which runs through Brandywine. Tutman’s family has lived in the area for seven generations. His company is identified as co-complainant in the suit.

“Brandywine seems to be getting more than its share of heavy industry and power generating uses,” Tutman said. “National experience teaches us that projects like high-polluting power plants typically go to areas with the least political power and the most people of color—and also in neighborhoods where the clean air, water and open space are most at risk.”

“It is time for honest conversation about the future of Brandywine and its residential population with respect to fairness, equity and self-determination,” he continued.

Research has shown that minorities in the U.S. are disproportionately affected by air pollutants. A University of Minnesota study found that nonwhite communities face nitrogen dioxide exposure at a rate 38 percent higher than white communities. Researchers estimate the inequity accounts for 7000 deaths per year.

The lawsuit said the Mattawoman plant would burden the area’s currently unhealthy levels of ozone at the ground level.

“The air in Prince George’s County, which includes Brandywine, already fails to meet the national air quality standard for ozone, which was set by EPA at the level determined to be requisite to protect public health,” the claim reads.

“Approval of the Mattawoman plant will make this air quality problem worse by increasing local emissions of two major contributors to the formation of ground‐level ozone, nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds.”

Ozone is a known contributor to asthma, which African-Americans suffer from at increased rates. The Maryland Department of Health reports Black people in the state are nearly 2.5 times more likely to die from the respiratory disease.

Panda Power Funds’ vice president of investor relations and public affairs challenged the claim as “meritless” and maintained that the Maryland commission thoroughly investigated environmental risks prior to the approval.

“The Maryland Public Service Commission undertook a lengthy and comprehensive analysis of a wide range of issues in granting the Mattawoman Project’s Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity,including the issues raised in the complaint,” Bill Pentak said, according to the Washington Post, ” The complaint is without merit, and we are confident there have been no violations of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act.”

Environmental racism is a systematic problem in the United States. Socially and economically disadvantaged people disproportionately live in close proximity to hazardous facilities of all kinds.

The U.S. General Accounting Office notes three out of every five African-Americans living well below the poverty line are also living in areas situated close to toxic waste sites.

In the southeast is Mossville, a predominately Black unincorporated community just outside of Lake Charles in Calcasieu Parish, Louisiana. The tiny settlement was founded by freedman Jack Moss in 1790. A total of 14 hazardous facilities surround the enclave, leaving the air, soil and water filled with toxins. In 1998, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention took blood samples from 28 residents and found dioxin levels were three times the national average. Another study uncovered that 84 percent of residents had a central nervous system disorder.

Sasol, a Johannesburg-based chemicals company, bought out the remaining inhabitants to pave the way for a massive $21-billion dollar expansion.

Then there is the case of Chester, Pennsylvania, a town that is nearly 75 percent African-American with a median household income of less than $30,000, according to the 2010 census. Four toxic and hazardous waste treatment facilities, including the country’s largest infectious medical waste center, call this city home. The EPA completed a six-month risk assessment study of the city in 1994 and found Chester’s infant mortality rate was the highest in the state, the mortality and lung cancer rate was 60 percent higher than Delaware county, and 60 percent of children Chester had blood-lead concentrations higher than the maximum recommended.

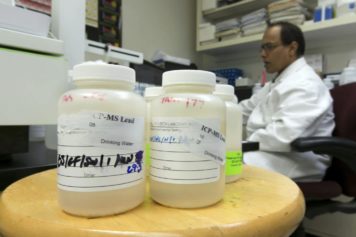

And the latest, most publicized incidence of environmental injustice comes from Flint, Michigan, where residents have been exposed to toxic levels of lead through the tap water. The state switched the city’s water supply from Lake Huron to nearby Flint River two years ago, in a money-saving scheme. Officials failed to properly treat the river water, causing lead from older pipes to leak into the city supply.