Couple counting money — Image by © Jose Luis Pelaez Inc/Blend Image/Blend Images/Corbis

A new report from Nielsen, “The Increasingly Affluent, Educated and Diverse,” explores the “untold story” of African-American consumers, particularly Black households earning $75,000 or more per year. According to the report, Black people in this segment are growing faster in size and influence than whites in all income groups above $60,000. And as African-American incomes increase, their spending surpasses that of the total population in areas such as insurance policies, pensions and retirement savings.

“These larger incomes are attributed to a number of factors, including youthfulness, immigration, advanced educational attainment and increased digital acumen. As these factors change African-Americans’ decisions as brand loyalists and ambassadors, savvy marketers are taking notice,” according to Cheryl Pearson-McNeil, Senior Vice President U.S. Strategic Community Alliances and Consumer Engagement, and Saul Rosenberg, Chief Content Officer at Nielsen.

According to Nielsen, the “youthfulness and vitality” among Black consumers are being driven by a diverse influx of immigrants, who make up one in 11 African-Americans, or 8.7 percent. Further, there has been substantial education growth among Blacks, with high school graduation rates exceeding 70 percent, outpacing the growth for all students nationwide.

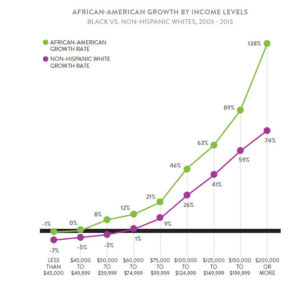

In addition, Blacks are making gains in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) careers, helping to fuel income gains. The largest increase for Black households was in the number of households making over $200,000, an increase of 138 percent compared to a total population increase of 74 percent.

Nielsen

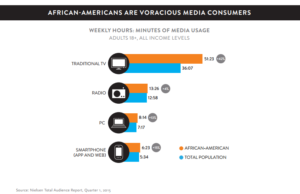

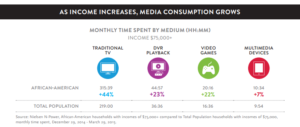

“The year 2015 represents a tipping point for African-Americans. As voracious media consumers, powerful cultural influencers experiencing burgeoning population growth create an unprecedented impact across a broad range of industries, particularly in television, music, social media and social issues,” according to the report.

Black consumers are digitally empowered and well-versed in social media, helping to shape and shift the national discourse. And Black people are youthful — with an average age of 31.4 as opposed to 39 for whites and 36.7 for the total population — and rising in cultural influence, driving mainstream trends in music, television, music and other areas. Therefore, the report notes, those who market to Millennials and young people must reach Black youth.

Other results of the Nielsen report include evidence of strong Black growth among income earners above $100,000 in metro areas of the South, such as Augusta and Columbus, Georgia; Baton Rouge, Louisiana; and Aiken, South Carolina. The report also found that gatherings, festivals,

According to Nielsen, “African-American households spend more on basic food ingredients and beverages and tend to value the food preparation process, spending more time than average preparing meals. Other popular buying categories include fragrances, personal health and beauty products, as well as family planning, household care and cleaning products.”

The authors of this report emphasize that as the social and cultural clout of the Black consumer is on the ascendancy, it is incumbent upon advertisers and marketers of consumer brands to develop a long-tern game with the Black community.

As The Atlantic notes, Black buying power is expected to reach $1.2 trillion this year, and $1.4 trillion by 2020, according to the University of Georgia’s Selig Center for Economic Growth. That is so much combined spending power that it would make Black America the 15th largest economy in the world in terms of Gross Domestic Product, the size of Mexico based on World Bank data. By comparison, in 1990, Black buying power was $320 billion. As the largest consumer group of color, in a nation that is becoming increasingly darker, this trend will only continue to have its impact on the U.S.

But in the end what does all of this really mean? We know that the Black community has much money at its disposal. What is the end goal for Black consumers, to merely buy more “stuff” that depletes in value and gets us nowhere, or rather to invest, own and build our wealth?

As corporate America and the business community vie for the patronage of the African-American community, Black dollars must serve as leverage. Black consumers must use their resources wisely — reward friends and punish foes accordingly, support Black-owned business and those brands who are in sync with our interests, values and aspirations. People and forces outside of our community want our business, but many will do little to nothing for it, or more importantly, for us, with no investments in our community and no jobs for Black people. Consider that companies spend $75 billion a year on advertising, but only three percent of that goes to Black publications, Black TV and radio stations and the casting of Black actors, as Pearson-McNeil told Marketplace.

And yet, Black folks don’t have jobs because they are creating so many jobs for other communities. For all of this wealth, we don’t feel wealthy because we are sending all of our money outside the Black community. As Dr. Boyce Watkins noted we need to harness that wealth. He said that with over $1 trillion, one can buy: 1,000 NFL teams; 3,000 predominantly white universities; the annual budget of 1.4 million charter schools across the nation; pay the tuition at Howard University for 50 million students for an entire year; buy 854,000 community centers; purchase NBC, ESPN and CBS and still have $1 trillion left over.

“When you look at Black unemployment, you see that Black unemployment is typically twice as high as white unemployment,” Watkins said. “Ask yourself this: Why is it that we give away $1.1 trillion in spending power when that $1.1 trillion could, according to most economists, create 12.2 million jobs in the Black community?” He added: “So, the point of all of this, the reason I’m telling you all of this, is because you have to understand one important, fundamental fact. Your money is your power, and you cannot give your power away.”

Further, as Black consumers are not respected, they continue to face institutional racism, policies that undermine their families, brutal police harassment tactics and mass incarceration. If #BlackLivesMatter, it also means that they must matter to Black people and that we can no longer pay good money to finance our own oppression. Martin Luther King and others had the right idea with the Montgomery Bus Boycott, as Black people were disrespected and forced to sit in the back of the bus. Similarly, Adam Clayton Powell led his own bus boycott in New York because the Transit Authority did not hire African-Americans, and he was involved in struggles against Harlem Hospital, Harlem drug stores, and other businesses that refused to hire Black employees. This is what economic boycotts and disinvestment in apartheid-era South Africa was all about.

As the Philadelphia Tribune reported last month, there is a new movement to economically empower the Black community throughout the country. LetsBuyBlack365 is a national grassroots movement that utilizes the online community and local networking to harness Black buying power, with a goal to create jobs and resources to help Black people. The organization’s video tells us all we need to know:

Nataki Kambon, a spokeswoman for the group, told the Tribune that this is a critical time for their efforts, as Black people watch with dismay as Black people are killed by police and the offending officers are not indicted. “What stands out most is that these things don’t happen in communities where they have political power. Political power comes from having economic power, through having businesses that can lobby and represent their interests,” Kambon said. “It puts empowerment on the individual to say, ‘What can I do right now? I can’t do anything about Sandra Bland, I can’t do anything about some of these other people but I can do something about political power in order to have some sort of social justice for the future,’” she added.

“If our communities are to change economically, it is going to be up to the African-American community and business leaders lead the charge. We can help win the war on poverty in our communities,” said Chet Riddick, head of the Alpha Enterprise Group. Riddick told the Tribune that Alpha has formed a purchasing agreement with Let’s Buy Black LLC. “It is important for our African-American businesses to figure out how to grow to scale because if we grow to capacity, we can then hire more people from out of own communities. We would be able to train and hire people from our own community so they would be able to lead productive lives,” he added.

Meanwhile, the Prosperity Foundation is creating a philanthropic vehicle to sustain and improve the state of Black America. “Leveraging our money to create any and everything to move our agenda and people forward — that’s the goal,” Prosperity Foundation founder and President Howard K. Hill told the New Haven Register. “We want to help as many of our people as possible, not just on the granting side, but as well as job creation.”

The foundation plans to create a statewide African-American community foundation in Connecticut, which they hope to duplicate nationwide. “In many areas of our community there are often times layers of distrust which prevent us from moving forward as a collective unit. It’s a result of living in America, where we’ve been systematically oppressed and encouraged not to be a unit,” Hill added. “We have a lot to heal from and creating something for ourselves for future generations is going to be a very difficult process,” he said. “It’s a process we need to continue to work at in order to change the outcomes for our community.”