According to a recent report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the national unemployment rate fell to 5.3 percent. Economists and policymakers eagerly discussed how close the current average is to the 5.0 to 5.2 percent Federal Reserve analysts say will signal full employment in the nation.

However, that percentage masks the unemployment disparities between white Americans and minorities across individual states.

Right now the national unemployment rate for white Americans is about 4.6 percent, for Hispanics, it’s 6.5, and for Blacks, 9.1.

On the record, Washington, D.C., hit the peak of Black unemployment with a 14.2 percent rate. New Jersey followed with 13 percent, South Carolina was at 12.8 percent, and Illinois at 11.5 percent. Tennessee holds the lowest state of Black unemployment, which is equivalent to the highest rate of white unemployment in West Virginia.

Historically, Black unemployment has exceeded white unemployment nationally in every single month since the Bureau of Labor Statistics began keeping records. It has been at least two-thirds higher, every month.

Valerie Wilson, the director of the Program on Race, Ethnicity and the Economy at the Economic Policy Institute, expressed that recovery only began for Black and Hispanic Americans in 2014. “That’s when you saw the greatest improvements in the unemployment rate, the employment-population ratio and labor-force participation,” she said.

Many factors are linked to why unemployment in the Black community is so high. Some include education and previous work experience. But even as the younger generation of Black students is graduating college at higher rates, a piece of paper is no match against systemic racial discrimination in the workforce.

Researchers at the Center for Economic Policy Research conducted an analysis in 2014 and found 12.4 percent of Black college graduates aged 22 to 27 were unemployed, compared with 5.6 percent of all college graduates in the same age group.

A famous 2009 study by Devah Pager, Bruce Western and Bark Bonikowski used actors, one Black, one white and one Hispanic, to apply for entry-level positions in New York City. The study found that Blacks without a criminal record had the same chance as whites with a stated criminal record (i.e., who listed their parole officers as a reference). “The findings suggest that a black applicant has to search twice as long as an equally qualified white applicant before receiving a callback or job offer from an employer,” the authors wrote.

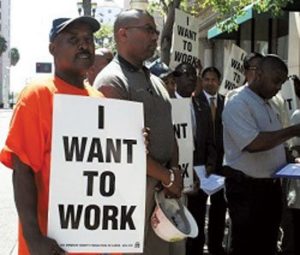

It proves that the state of Black unemployment is not linked to inactivity but to the discriminatory behaviors of employers across America. Blacks with degrees, no criminal history, previous work experience are still less likely to be called in for job interviews or hired compared to white or Hispanic counterparts.

Wilson’s analysis shows that only 11 states had a Black unemployment rate below 10 percent. Eight states have seen unemployment rates fall below pre-recession levels. In Alabama, the African-American unemployment rate is more than twice what it was pre-recession: 10.9 percent, compared with less than 5 percent throughout 2007.

Out of all racial groups in America, the Black community took the worst hit in the recession, each household losing an estimated one-third of its wealth. As the nation’s economists celebrate progress, some of those same Black families are still looking for work today.