The country was Haiti, the Caribbean nation that’s often seen by outsiders as a metaphor for poverty and disaster. Yet rarely are Americans confronted with their own hand in its misfortunes.

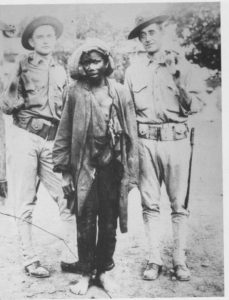

On Tuesday, a group of protesters marched to the U.S. Embassy in the Haitian capital Port-au-Prince in commemoration of the grim legacy of the U.S. occupation, which began in July 1915 after President Woodrow Wilson used political chaos and violence in the country as grounds to intervene. Some in Washington feared the threat of competing French and German interests in the Caribbean.

The liberal, democratic values Wilson so famously championed in Europe were not so visible in Haiti, a largely Black republic that since its independence from France a century earlier had been regarded with fear and contempt by America’s white ruling classes. “Think of it! N-ggers speaking French,” quipped William Jennings Bryan, Wilson’s secretary of state, in a chilling echo of the Jim Crow-era bigotry of the time.

Though framed as an attempt to bring stability to an unstable, benighted land, the United States “also wanted to make sure that the Haitian government was compatible to American economic interests and friendly to foreign investment,” writes Laurent Dubois, a Duke University academic and author of “Haiti: The Aftershocks of History.”

“In Haiti, the reality of American actions sharply contradicted the gloss of [American leaders’] liberal protestations,” wrote the historian Hans Schmidt, whose 1971 book on the U.S. occupation is still a widely cited text. “Racist preconceptions, reinforced by the current debasement of Haiti’s political institutions, placed the Haitians far below levels Americans considered necessary for democracy, self-government, and constitutionalism.”

It was also a moment where Washington did little to disguise its sense of imperial entitlement in the neighborhood; a number of fledgling governments in the Caribbean and Central America all suffered U.S. invasions and the imposition of policies favorable to American strategic interests and big business. Banana republics didn’t just spring up on their own.

Read more at stripes.com